The Wheeled Body Shield

Item

Title (Dublin Core)

The Wheeled Body Shield

Subject (Dublin Core)

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

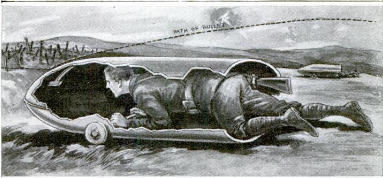

Caption: "This British invention is the latest scheme developed for protecting infantry men during offensive operations against enemy trenches"

extracted text (Extract Text)

SINCE Europe has been merged in hostilities, scarcely a month has passed unmarked either by the development of some new agent of destruction, or the introduction of some new medium of defense. The creative genius of half the world has been concentrated in an effort to make war more terrible on the one hand, and safer on the other. And first one belligerent and then the other has met crucial emergencies by ingenious, not to say startling, inventions.

The apparent deadlock on the western frontier has presented a perplexing situation. For months the armies have fought battles more sanguinary than Waterloo without making progress except in terms of yards. Trench warfare has been responsible for this. Any kind of an offensive movement has meant heavy losses.

To make the trench less secure for the enemy is an object which each of the belligerents is striving to accomplish. A step in .this direction is found in the work of a British inventor who has developed a wheeled body shi eld that affords immunity from rifle bullets and shrapnel when advancing upon fortified positions. The body of this is constructed of tempered-steel plates, the front so rounded and tempered that bullets strike the surface at an angle

and glance off without doing harm. The rear is open, while the interior is just large enough to accommodate one soldier, who rests on his hands and knees. The device is propelled forward by pushing against the ground with one foot. A long slit in the front part terminating in a porthole forms a lookout for the soldier and also a loophole through which to fire. When

within a few yards of an objective point the fighter leaves the armored shell and charges in the usual way.

It was inventive skill applied in a different channel that made possible the construction of a gigantic steel network across the Narrows in the Dardanelles to check the operations of the allies’ submarines in the Sea of Marmora. The barrier extends some 75 ft. beneath the water and is long enough to block the entire channel from Chanak Kalessi in Asia Minor to Namazieh on the European side. It is composed of a number of great nets, each approximately GOO feet long, moored end to end by means of buoys and anchors. The middle portions of the units consist of torpedo nets from German and Turkish battleships, while the buoys were taken from the Sea of Marmora and the Black Sea where they had been used to aid navigators.' Attached to both ends of these members are heavy nets of 5-ft. tri

The Wheeled Body Shield in Use: Tnis British Invention Is the Latest Scheme Developed for Protectin’ Infantrymen during Offensive Operations against Enemy Trenches

angular mesh, made of %-in. iron wire. Interlaced over the whole of the latter sections are reinforcing skeletons of Manila and wire cables, woven in 30-ft. squares. The units are bound by heavy cables fixed at the top and bottom, and to these the anchor and buoy chains are secured. The former are placed at intervals of 120 ft., while the buoys are but a short distance apart. The nets are suspended perpendicularly and reach within 100 ft. of each shore line, or to water too shallow to float a submarine. The open spaces intervening between the nets are not sufficiently great to permit the passage of a submersible.

The British submarines have not been entirely blocked by the net, although their activities have been hampered. The French submarine “Mariotte,” however, was caught in the trap early in August while attempting to dive beneath it. Most American undersea boats are capable of submersion to a much greater depth than 80 ft.—which is necessary to pass beneath the barrier—but the rumor is current that the British and the French crafts leak badly when the feat is undertaken. When the “Mariotte” attempted the dive it took water so fast that its commander was forced to rise, and in so doing the starboard diving plane fouled the net, entrapping the vessel, which was almost immediately captured by a Turkish patrol boat.

At the beginning of the war there was a deep-rooted belief that the submarine was destined to banish dread-naughts and battleships from the seas. Except for the attacks upon merchant vessels by German undersea craft, which have been negligible so far as real military value is concerned, the submersible has done very little of especial importance. This represents a striking case in which inventive genius has met one of war’s serious emergencies. The submarine has become as vulnerable a boat as any afloat. Inventions, of which the Dardanelles net is but one example, have been responsible for this changed condition.

The net across the Narrows has been a practical means of defense because there is little tide in the eastern Mediterranean to disturb it. This condition is not true in the waters about England, where a different scheme has been used by the British admiralty with remarkable results. It has been repeatedly stated in press reports that in a period of about two months following the first week in May, Ger-many lost more than 60 submarines, among which were listed the “U” boats Xos. 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 15, 16, 18, 22, 23, and 24. This, it is claimed, has been accomplished by literally seining the boats. The nets used for this are made in lengths of about 170 ft. with heavy iron wire. They are usually about 27 ft. in width and of 15-ft. mesh. When in use they are stretched between the bows of two oil-burning destroyers and buoyed by means of large blocks of wood attached to the binding cables along the top. When an enemy submarine is sighted, the fast destroyers cut ahead of the vessel and moor the net directly in the path it is pursuing. The rough condition of the water in the North Sea greatly restricts the range of a periscope, making it effective for a distance of only about a mile. This permits the destroyers to set the trap, after observing the course a submarine is taking, and escape unnoticed. The result is that the submersible proceeds, ignorant of danger, and drives its nose into the netting, the top of which is about eight or ten feet beneath the surface.

More surprises in the way of new death-dealing and defensive machines have been introduced on the battle fields, however, than at sea. Machine guns have played a more important part in this war than ever before. These implements are very expensive and in no case is any of the armies supplied with as many of them as it could use. The French, however, have overcome their shortage by a most clever makeshift. By utilizing the rifles of dead and wounded soldiers, they have constructed a very ingenious and quite satisfactory type of “machine gun.” The weapons are set in rows in wooden frames mounted on the parapets of the trenches. Frequently as many as 20 guns are grouped in one of these batteries. By pulling a rod placed through the trigger guards of the rifles in each tier, all of the pieces arc discharged at one time. By using the magazine fire, about 40 bullets can be shot from a modern army rifle in one minute. This explains how such a battery of guns can discharge from 600 to 800 shots a minute, which is equivalent to the work of a machine gun. The loading requires more time than that of a machine gun, but the firing itself is just as rapid.

When the Germans commenced fighting with poisonous gases in the western war zone it required only a short time for the allies to equip their soldiers with respirators, and install warning signals in the trenches. These agents practically neutralized the effectiveness of this means of fighting. A further defense against asphyxiation has been suggested, however, which shows how truly the war is a conflict of wits. The use of gas depends upon there being a gentle breeze to. carry the fumes to the enemy’s positions. A strong wind is as useless for this purpose as is a calm. The new plan is to combat the gas clouds with counter air currents, just as our western pioneers once fought prairie fires with fire. This it is proposed to do by installing a series of fan blowers in the advanced trenches to create updrafts and raise the vapor clear of the lines.

These, when operated by hand, would be placed at intervals of 10 or 12 feet, and connected with large pipes extending through the base to the front of the earthwork. The spaces between the units would be increased when large, motor-propelled fans were installed. Anyone who is familiar with the blowing force of an aerial propeller, will readily appreciate how effectively a scheme of this kind might be worked out.

Ingenuity of a much different character has been shown by the Germans in connection with their aerial activities. Before hostilities commenced, night aeroplane flying was not practiced to any extent. A few months of war showed, however, that the flying machine could accomplish much under the cover of darkness that it could not attempt without extreme hazard in the daytime. One of the greatest problems encountered by a pilot at night is that of landing safely. To ameliorate this condition the Germans have devised lighting systems for their army aerodromes which assist airmen in alighting after nocturnal voyages. A powerful white light is installed in a large pit dug in the middle of a field and covered with heavy plate glass. Surrounding this central light, at distances of about 250 ft. from each corner of the pit, and corresponding to the cardinal points of the compass, are four red lights similarly fixed in the ground. These are controlled by a switch working in connection with a wind vane. When a red light shows at the east of the field, the aviator knows that the wind is blowing* in that direction. As he approaches an aerodrome he signals the attendants by flashing a revolver. The lights are then turned on, the big white glow indicating where to land and the relative distance to the ground,

while the red patches announce the direction of the wind. Ue turns the nose of his machine toward the white light and glides to the earth, avoiding the dangers of being caught by a side wind or misjudging the distance.

These illustrate a few of the numerous ways in which the war’s emergencies are being met. For every new instrument of destruction introduced, some means is promptly developed to counteract its effect or nullify its efficiency. And for every fresh obstacle encountered in the ever-changing methods of war, some scheme is devised for surmounting it.

The apparent deadlock on the western frontier has presented a perplexing situation. For months the armies have fought battles more sanguinary than Waterloo without making progress except in terms of yards. Trench warfare has been responsible for this. Any kind of an offensive movement has meant heavy losses.

To make the trench less secure for the enemy is an object which each of the belligerents is striving to accomplish. A step in .this direction is found in the work of a British inventor who has developed a wheeled body shi eld that affords immunity from rifle bullets and shrapnel when advancing upon fortified positions. The body of this is constructed of tempered-steel plates, the front so rounded and tempered that bullets strike the surface at an angle

and glance off without doing harm. The rear is open, while the interior is just large enough to accommodate one soldier, who rests on his hands and knees. The device is propelled forward by pushing against the ground with one foot. A long slit in the front part terminating in a porthole forms a lookout for the soldier and also a loophole through which to fire. When

within a few yards of an objective point the fighter leaves the armored shell and charges in the usual way.

It was inventive skill applied in a different channel that made possible the construction of a gigantic steel network across the Narrows in the Dardanelles to check the operations of the allies’ submarines in the Sea of Marmora. The barrier extends some 75 ft. beneath the water and is long enough to block the entire channel from Chanak Kalessi in Asia Minor to Namazieh on the European side. It is composed of a number of great nets, each approximately GOO feet long, moored end to end by means of buoys and anchors. The middle portions of the units consist of torpedo nets from German and Turkish battleships, while the buoys were taken from the Sea of Marmora and the Black Sea where they had been used to aid navigators.' Attached to both ends of these members are heavy nets of 5-ft. tri

The Wheeled Body Shield in Use: Tnis British Invention Is the Latest Scheme Developed for Protectin’ Infantrymen during Offensive Operations against Enemy Trenches

angular mesh, made of %-in. iron wire. Interlaced over the whole of the latter sections are reinforcing skeletons of Manila and wire cables, woven in 30-ft. squares. The units are bound by heavy cables fixed at the top and bottom, and to these the anchor and buoy chains are secured. The former are placed at intervals of 120 ft., while the buoys are but a short distance apart. The nets are suspended perpendicularly and reach within 100 ft. of each shore line, or to water too shallow to float a submarine. The open spaces intervening between the nets are not sufficiently great to permit the passage of a submersible.

The British submarines have not been entirely blocked by the net, although their activities have been hampered. The French submarine “Mariotte,” however, was caught in the trap early in August while attempting to dive beneath it. Most American undersea boats are capable of submersion to a much greater depth than 80 ft.—which is necessary to pass beneath the barrier—but the rumor is current that the British and the French crafts leak badly when the feat is undertaken. When the “Mariotte” attempted the dive it took water so fast that its commander was forced to rise, and in so doing the starboard diving plane fouled the net, entrapping the vessel, which was almost immediately captured by a Turkish patrol boat.

At the beginning of the war there was a deep-rooted belief that the submarine was destined to banish dread-naughts and battleships from the seas. Except for the attacks upon merchant vessels by German undersea craft, which have been negligible so far as real military value is concerned, the submersible has done very little of especial importance. This represents a striking case in which inventive genius has met one of war’s serious emergencies. The submarine has become as vulnerable a boat as any afloat. Inventions, of which the Dardanelles net is but one example, have been responsible for this changed condition.

The net across the Narrows has been a practical means of defense because there is little tide in the eastern Mediterranean to disturb it. This condition is not true in the waters about England, where a different scheme has been used by the British admiralty with remarkable results. It has been repeatedly stated in press reports that in a period of about two months following the first week in May, Ger-many lost more than 60 submarines, among which were listed the “U” boats Xos. 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 15, 16, 18, 22, 23, and 24. This, it is claimed, has been accomplished by literally seining the boats. The nets used for this are made in lengths of about 170 ft. with heavy iron wire. They are usually about 27 ft. in width and of 15-ft. mesh. When in use they are stretched between the bows of two oil-burning destroyers and buoyed by means of large blocks of wood attached to the binding cables along the top. When an enemy submarine is sighted, the fast destroyers cut ahead of the vessel and moor the net directly in the path it is pursuing. The rough condition of the water in the North Sea greatly restricts the range of a periscope, making it effective for a distance of only about a mile. This permits the destroyers to set the trap, after observing the course a submarine is taking, and escape unnoticed. The result is that the submersible proceeds, ignorant of danger, and drives its nose into the netting, the top of which is about eight or ten feet beneath the surface.

More surprises in the way of new death-dealing and defensive machines have been introduced on the battle fields, however, than at sea. Machine guns have played a more important part in this war than ever before. These implements are very expensive and in no case is any of the armies supplied with as many of them as it could use. The French, however, have overcome their shortage by a most clever makeshift. By utilizing the rifles of dead and wounded soldiers, they have constructed a very ingenious and quite satisfactory type of “machine gun.” The weapons are set in rows in wooden frames mounted on the parapets of the trenches. Frequently as many as 20 guns are grouped in one of these batteries. By pulling a rod placed through the trigger guards of the rifles in each tier, all of the pieces arc discharged at one time. By using the magazine fire, about 40 bullets can be shot from a modern army rifle in one minute. This explains how such a battery of guns can discharge from 600 to 800 shots a minute, which is equivalent to the work of a machine gun. The loading requires more time than that of a machine gun, but the firing itself is just as rapid.

When the Germans commenced fighting with poisonous gases in the western war zone it required only a short time for the allies to equip their soldiers with respirators, and install warning signals in the trenches. These agents practically neutralized the effectiveness of this means of fighting. A further defense against asphyxiation has been suggested, however, which shows how truly the war is a conflict of wits. The use of gas depends upon there being a gentle breeze to. carry the fumes to the enemy’s positions. A strong wind is as useless for this purpose as is a calm. The new plan is to combat the gas clouds with counter air currents, just as our western pioneers once fought prairie fires with fire. This it is proposed to do by installing a series of fan blowers in the advanced trenches to create updrafts and raise the vapor clear of the lines.

These, when operated by hand, would be placed at intervals of 10 or 12 feet, and connected with large pipes extending through the base to the front of the earthwork. The spaces between the units would be increased when large, motor-propelled fans were installed. Anyone who is familiar with the blowing force of an aerial propeller, will readily appreciate how effectively a scheme of this kind might be worked out.

Ingenuity of a much different character has been shown by the Germans in connection with their aerial activities. Before hostilities commenced, night aeroplane flying was not practiced to any extent. A few months of war showed, however, that the flying machine could accomplish much under the cover of darkness that it could not attempt without extreme hazard in the daytime. One of the greatest problems encountered by a pilot at night is that of landing safely. To ameliorate this condition the Germans have devised lighting systems for their army aerodromes which assist airmen in alighting after nocturnal voyages. A powerful white light is installed in a large pit dug in the middle of a field and covered with heavy plate glass. Surrounding this central light, at distances of about 250 ft. from each corner of the pit, and corresponding to the cardinal points of the compass, are four red lights similarly fixed in the ground. These are controlled by a switch working in connection with a wind vane. When a red light shows at the east of the field, the aviator knows that the wind is blowing* in that direction. As he approaches an aerodrome he signals the attendants by flashing a revolver. The lights are then turned on, the big white glow indicating where to land and the relative distance to the ground,

while the red patches announce the direction of the wind. Ue turns the nose of his machine toward the white light and glides to the earth, avoiding the dangers of being caught by a side wind or misjudging the distance.

These illustrate a few of the numerous ways in which the war’s emergencies are being met. For every new instrument of destruction introduced, some means is promptly developed to counteract its effect or nullify its efficiency. And for every fresh obstacle encountered in the ever-changing methods of war, some scheme is devised for surmounting it.

Language (Dublin Core)

eng

Temporal Coverage (Dublin Core)

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

1915-11

Rights (Dublin Core)

Public Domain