-

Titolo

-

The Nazis figured it would take 3,5 years to land our military railroads in France - but- they are highballing now

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

The Nazis figured it would take 3,5 years to land our military railroads in France - but- they are highballing now

-

extracted text

-

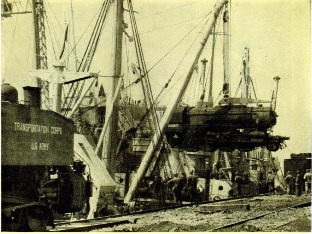

ON JUNE 6, 1944—D-day—more than

20,000 railroad cars and almost 1,500

locomotives sat on sidings and in marshal-

ing yards of southern England. They lay in

strings, mile on mile, like delicately articu-

lated centipedes.

The Germans knew they were there. Air

reconnaissance had told them so. They knew

what they were intended for. And they

weren't worried.

The Germans were sure that rolling stock

never could be brought across 100 miles of

white-capped water and landed in Nor-

mandy to carry supplies for the sustained

offensive necessary to drive them out of

France.

‘They held the ports. They would

hold them to the bitter end. After

that they would blow up the docks.

How could the British and the

Americans land heavy rolling stock

without ports? It was that simple.

Yet on D-day plus 38, long before

any Nazi-demolished port and its

docks had been reconstructed, those

cars and some light Diesel locomo-

tives from those English sidings

and yards began moving into

France. They went right in across

the sloping, sandy beaches in spite

of a 24-foot tide.

How this was done, how one of

the war's great engineering feats

was planned and executed, can now

be told for the first time.

Much had preceded that chapter

of the invasion. The Military Rail-

way Service of the Army's Trans-

portation Corps, which did the job,

Was warring on five continents.

It delivered supplies to China's

Ledo Road lifeline across rain-swollen riv-

ers. It had taken some of Mussolini's dis-

carded, rusted steam locomotives out of

bomb-pitted yards and put them to work in

Italy. It had transformed an Iranian rail-

road known as “the Shah's toy” into a

major supply route for rushing arms to the

harried Russians.

The United States Army knew, as all

armies know, that you can’t fight continen-

tal wars without railroads. That is why the

rolling stock and rail centers of the enemy

are A-1 priority targets of both tactical and

strategic air forces. That is why 42,000 men

and 2,000 officers were recruited from

America’s great civilian army of railroaders

for World War II. That is why American

locomotive manufacturers, who turned out

only 91 main-line units in 1940, began work-

ing around the clock after the Japs struck

Pearl Harbor. The United States became

the United Nations’ railroad arsenal.

America’s war of the rails began in Egypt

in 1942. The British needed help. Rommel

was knocking on the door to the Suez for an

ultimate junction with the Japanese press-

ing from the east.

Every time an Egyptian locomotive

chuffed, its steam and smoke drew fire from

a German strafing plane. So the United

States supplied Diesel-electrics to the Brit-

ish. It did more. It sent over the 760th

Diesel Shop Battalion to keep those locomo=

tives working. The British put their new

locomotives in the middle of trains where

German airmen seldom could distinguish

them from the boxcars—or, as Europeans

put it, the wagons.

At Naples the MRS plodded into the line

of fire to undo damage done by the Germans.

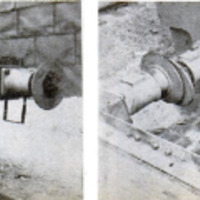

German demolition work had been typically

thorough. Rails looked like pretzels. Loco-

motive boilers were sieves. A device de-

signed with diabolical cunning had ripped

up untold miles of ties.

The Italians shrugged and said mo one

could make a railroad out of that debris.

The British rubbed their chins and said it

would take weeks.

Five days after the American railroaders

walked ashore, they had a railroad running!

That job was less complicated than the

one they undertook in the mountain-ridden

little kingdom of Iran. There had been built

“the Shah's toy,” a railroad that started

nowhere and ended nowhere. Riza Shan

Pahlevi, the country’s Cossack ruler, had

sunk $100,000,000 in it. It snaked up from

the Persian Gulf at 65 feet below sea level,

in temperatures running to 130 degrees, in"

to the bitter cold of the Elbruz and Luristan

mountains. It threaded through 225 tunnels

before it reached the capital, Teheran. From

Teheran the railroad splayed out to the

northwest and northeast. All told, it had

1,500 miles of roadbed, all single-tracked.

The Russians needed that railroad. In

the very critical days of early 1943, the MRS

moved in. It found that the British and

American locomotives in use were not pow-

erful enough to negotiate a roadbed with

hairpin turns at a speed necessary to meet

the Russian target of supply at the Caspian

Sea. It found that the Persian Gulf port

would not accommodate the deep-draft ships

streaming over from America.

A fleet of Diesel-electrics— streetcars,”

in railroad slang—was ordered. A hundred

miles of new line was built from a whistle

stop called Awaz to a better port at Khor-

ramshahr. By May “the Shah's toy" was

delivering 18 percent more tonnage than the

Russians had specified, notwithstanding the

fact that natives complicated operations by

stealing the oiled stuffing out of journal

boxes to make camp fires.

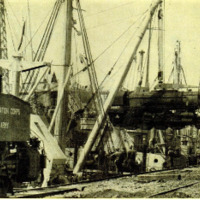

The Normandy operation was something

else. Never in a major war had rolling stock

been landed on a shore where the enemy

stood at the battlements.

That is where a man named Sidney H.

Bingham comes in. In peacetime Bingham

ran the New York subways. Emphatic, ima-

ginative, he was put into a uniform with

Transportation Corps insignia on his lapels

and assigned to planning railway operations

for the invasion.

The Military Railway Service had col-

lected the roiling stock for the job. By

ordinary means it would take 3 1/2 years to

get those locomotives and cars to France,

even without German interference. That

was as fast as they could be shuttled over

in the train-carrying ships the British used

in trans-Channel work before the war.

Moreover, the British ships would need

docks for unloading.

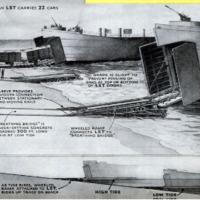

Sitting on a joint British-American board,

Bingham, a colonel, made a suggestion:

Why not load this stuff into U. S. Navy

LST's (landing ships, tank) and roll it across

the beaches? The LST's had little or no

draft, and he would figure out some way to

get the cars and a few Diesel locomotives

off the boats.

Somebody in the room snorted. That 24-

foot tide would allow just 90 minutes out of

each 24 hours for unloading on a beach,

granting the stuff could be unloaded on a

beach.

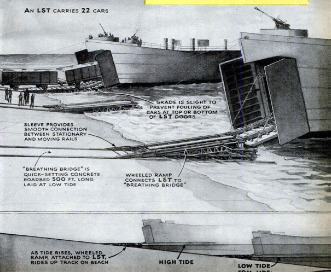

This was in July, 1942. Colonel Bingham

ignored the snort and set to work. Experi-

mentally he laid tracks in an LST. Then he

loaded rolling stock in it and sailed into

rough water to see whether the boat would

behave properly. It would.

Now for the big problem. He laid a

“breathing bridge” in quick-setting concrete

on an English beach at low tide, fitted a

wheeled ramp to the lip of the LST's cargo

deck, and rolled his cars ashore regardless

of the tide level.

Nobody snorted.

On D-day plus 25 Col. Bingham put down

four “breathing bridges” on a Normandy

beach at low tide. Thirteen days later he

started pushing converted LST's across the

100 miles of open water to the Cherbourg

peninsula. Each boat carried 22 cars. It

took him exactly 26 minutes to load in Eng-

land and exactly 21 minutes to unload in

France. He knew. He timed it.

By mid-October, aided by some of the

Cherbourg docks slowly coming back into

use after the usual Nazi destruction, he had

delivered a total of 20,000 cars and 1,300

locomotives.

This seeming delay in delivering the big

locomotives was part of the plan. Gen. Ber-

nard Montgomery stated flatly that he would

have no steam locomotives in his area of

operations during go first critical weeks.

The railroad crews, he complained, were al-

ways right up behind the front lines, and

the smoke and steam made targets for

enemy artillery. So they used Diesels.

The Second Battle of France could not

have been fought without the Transporta-

tion Corps’ cars and locomotives. Of the

30,000 locomotives the French railroads nor-

mally operated, less than 4,000 were found

and most of these were in very bad shape.

The campaign in France lent eloquent

testimony to the role of the railroad in war.

In the 81 days that the “Red Ball Express,”

the truck supply route between Normandy

and Paris, operated while the French rail

lines were being refurbished, it toted a half

million tons of supplies. That much is being

carried every 23 days now by the rails sup-

plying the front.

The MRS is patterned strictly on ortho-

dox railroad organizations, The basic unit

is the Railway Operating Battalion, made up

of four companies. Each has its duties:

dispatching and supplies, track and signal

maintenance and maintenance of way,

roundhouse operation and equipment repair,

and the actual operation of the trains. A

battalion runs a division of about 100 miles.

Three or four Railway Operating Bat-

talions, together with a Railway Shop Bat-

talion, a Base Depot Company and a Mobile

Railway Workshop, make up a typical grand

division. That corresponds in scope and au-

thority to a general superintendent's domain

on an American railroad.

Maj. Gen. Charles P. Gross, chief of trans-

portation, is responsible for the MRS. Brig.

Gen. Andrew F. McIntyre, formerly of the

Pennsylvania, handles details at home.

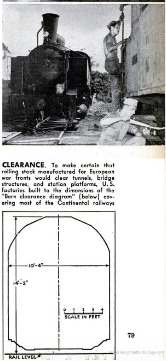

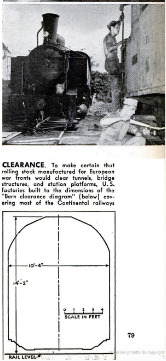

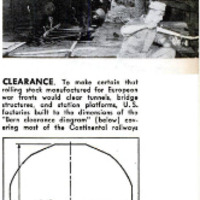

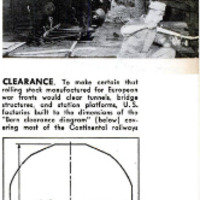

A lack of standardization complicates the

job. Clearances are the bane of the car and

locomotive designer's pencil. Even in peace-

time clearances lead to some fantastic rout-

ings. Any oversize shipment—one with con-

siderable “overhang,” projecting beyond a

car's head-on silhouette—bound from New

York to Washington, for instance, has to

travel by way of Harper's Ferry, Va. There

are some tunnels on the direct route that it

won't clear.

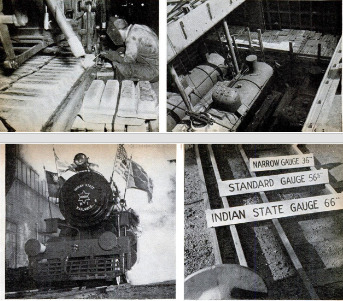

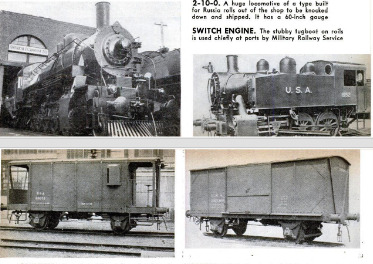

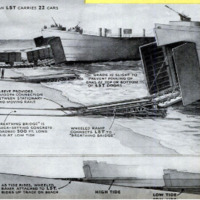

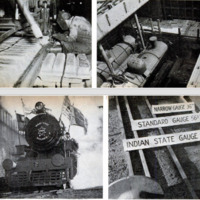

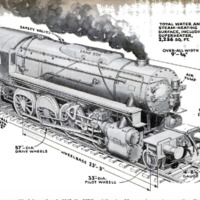

In manufacturing for the Russians, Amer-

: ican car and locomotive makers had few

prohibitions. The average width of rolling

stock in the United States is 10 feet, 8

inches; its height from the top of the rail, 15

feet. Russian stock runs to widths of more

than 12 feet and heights of more than 17.

In England, the width averages only 9 feet

and the height less than 13.

Cars and locomotives for England had to

be equipped with the exact opposite of the

American braking system. Over here com-

pressed air is used to keep the brake shoe

off the wheel; when the air is released the

brake clamps on. In England a vacuum in

the air line sucks the shoe onto the wheel.

American manufacturers discovered they

had to take the Russian temperament into

account in filling lend-lease orders. Spare

wheels had to be shipped by the thousands.

When a Russian locomotive engineer comes

to a grade and claps on the brakes, he takes

no half measures.

They discovered they had to equip loco-

motives intended for India with extra-bril-

liant headlights. That was so the engineers

could see the sacred cows, wild elephants,

and human foot traffic on the right of way.

There was the field problem of increasing

the traffic on Indian railroads to deliver sup-

plies to the Ledo Road truck route and to

the airfields used by planes flying “the

Hump.” The Bengal and Assam Railway

had twin gauges, extra wide and narrow. It

wound north from Calcutta for 800 miles,

and then all the supplies had to be trans-

shipped on to meter gauge for almost 1,000

miles more.

Hol 91 Of 16 asl oc JouIs Le harlow

gauge had been inoperative for as much as

six months of the year when rivers boiled

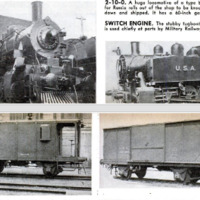

out of their banks. U. S. railroad men re-

channeled the rivers and built a bridge as a

substitute for the car ferries traditionally

used for the crossing of the mile-wide Brah-

maputra River. Where three or four trains

a day ran before the war, from 21 to 25 are

now operating with 12,000 wagons and 550

locomotives of the 2-8-2 type, marked

“Made in U. S. A.”

The MRS has had its compensations.

When it landed behind the assault troops in

North Africa, what should meet its delighted

eye but a score of “General Pershing” loco-

motives that the United States shipped to

France for World War I. They were as good

as ever.

German railroads, with 44,000 miles of

standard gauge, present no great problem

to the Army. Nor will the railroads of

China and Japan. In row upon row of secret

files in Washington's sprawling Pentagon

Building arz details on Japanese and Chi-

nese railroads.

The Military Railway Service of the

Army's Transportation Corps has only one

problem it hasn't solved. It would like to

know how to keep monkeys from swarming

into passenger carriages when trains stop

at stations in India.

-

Autore secondario

-

Devon Francis (writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1945-02

-

pagine

-

76-83,220, 224

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.43.40.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.43.40.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.43.45.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.43.45.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.43.50.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.43.50.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.43.50.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.43.50.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.43.59.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.43.59.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.44.06.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.44.06.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.44.13.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.44.13.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.44.13.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.44.13.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.44.26.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.44.26.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.44.34.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.44.34.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.44.40.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.44.40.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.44.47.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.44.47.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.44.54.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.44.54.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.44.59.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.44.59.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.45.06.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 16.45.06.png