-

Titolo

-

The truth about Japan's "mystery ships"

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

The truth about Japan's "mystery ships"

-

extracted text

-

TAKING shape beneath concealing roofs

of bamboo, in Japanese shipyards, war-

ships of secret design have long inspired

wild rumors. At last our advance across the

Pacific has forced the mystery craft out of

hiding. Now, for the first time, we know

what our Navy has to lick—and that infor-

mation will help it mightily to play its part

in the combination of sea, land, and air-

power pledged to the destruction of the

Japanese Empire.

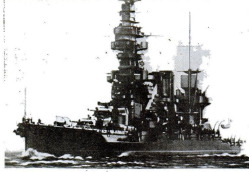

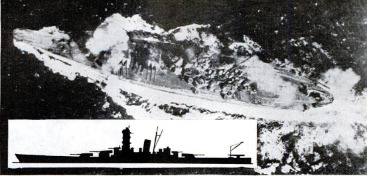

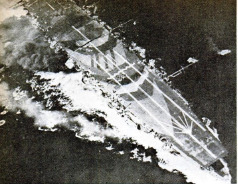

Tilustrating the latest in Nipponese battle-

ships, the Yamato and Musashi first showed

themselves in the Second Battle of the Phil-

ippines. A photograph snapped from a

U.S. Navy plane, while bombs made a

shambles of the Yamato’s superstructure,

enables any layman to analyze Japan's most

powerful warship class.

Study of the picture indicates a vessel ap-

proaching the 45,000-ton size of our Iowa

class—believed to be the only men-of-war in

the world that outclass it, ship for ship. The

Yamato mounts its main battery of nine big

guns, probably 16-inchers, in the first triple

turrets to be installed aboard Jap battle-

wagons. As in standard American practice,

two turrets have been placed forward and

one aft—the latter all but obscured in the

picture by smoke and wreckage. Since the

battle, Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz

has announced that the Musashi, sister ship

of the Yamato, is now definitely known to

have blown up and sunk as the result of

damage inflicted on her by U.S. carrier

planes in the same engagement.

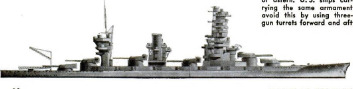

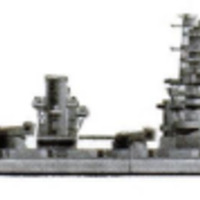

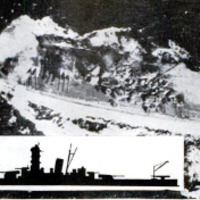

Battleship-carriers, strangest of naval hy-

brids, have appeared in the converted Jap

battleships Isc and Hyuga. The freak ships

appear to combine the worst features of

both types. Each provides a

“flight deck” aft, a fraction of

the length of the smallest flat-

top and apparently suited only

to catapult launchings. For the

dubious advantage of the “car-

rier” feature, the two after tur-

rets of each vessel evidently

have been removed—a surpris-

ing sacrifice of firepower, which

Japan can ill afford in her re-

maining capital ships.

From what we now know of

Japan's tools of seapower, the

opposing lineups for the Battle

of Japan can now be estimated

within reasonable limits. At

most, Japan can probably mus-

ter no more than 11 battleships

to our 23—a proportion of more

than two to one in our favor. If

the Land of the Rising Sun has

another Yamato class battleship,

as naval circles here believe,

two of its capital ships are

modern, compared with 10 of

ours. These figures do not in-

clude our newly completed 27,-

000-ton Alaska and Guam, which

the U. S. Navy calls “large

cruisers”—a masterpiece of of-

ficial understatement.

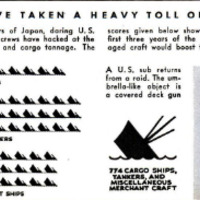

In other categories of fighting

ships — carriers, cruisers, de-

stroyers, submarines—the story

again is one of overwhelming

American superiority both in

numbers and in types. Due for

completion in 1945, the mam-

moth U. S. carriers Coral Sea

and Midway, will match the 45,-

000-ton displacement of our

mightiest battleships and will

provide a take-off run long

enough for the heaviest bombers

ever launched at sea. They will

dwarf even the 33,000-ton Sara-

toga, veteran of our carrier

forces, and the 13 or more Es-

sez-type carriers of more than

25,000-ton size that we have

completed since we entered

World War II. Our latest super-

destroyers, displacing 2,200 tons,

approach small cruisers in size

and armament. And now trans-

ports and cargo landing craft,

which formerly brought troops

and supplies to beachheads al-

ready secured, are giving way to

“assault ships” that take direct

part in amphibious fighting op-

erations. Comparatively shallow

draft enables them to launch

invasion barges and cargo

lighters close to shore, and

heavy armament covers land-

ing parties while they dig in.

Top priority has been given to

mass production of these as-

sault ships, designed especially

for use against Japan.

Assault transports, or APA's

for short, land a complete com-

bat team of hundreds of men.

Simultaneously, assault cargo

ships, or AKA's, bring up am-

munition and miscellaneous

supplies. Plans for a given op-

eration call for a definite ratio

of AKA's to APA's. Larger than standard

Atlantic landing craft, the assault trans-

ports provide commodious quarters and

anti-tropical ventilation, so that the men

will arrive fresh and full of fight after a

voyage lasting for weeks instead of days.

Converting destroyers for use as fast

troop transports provides another way of

landing invasion forces. First tried out some

years ago, the experiment has proved so

successful that the APD's, as they are called, have

become standard ships of the U. S. Navy.

“Beach rockets" of 4 1/2-inch size, which blast shore

defenses with the punch of 105-mm. artillery shells,

now are fired in salvos by specialized landing craft

carrying hundreds of them, according to a recent

statement by Rear Admiral George F. Hussey, Jr.,

Chief of the Navy Bureau of Ordnance. Owing to

the stepped-up tempo of the Pacific war, rocket-firing

ships and planes will require a threefold increase

over the nearly $100,000,000-a-month production of

the projectiles a few months ago, the Navy esti-

mates. Besides explosive rockets, the Navy employs

incendiary rockets for obtaining range,

and smoke rockets for screening

troops.

“This should be bad enough news for

Japan's naval commander in chief,

‘Admiral Mineichi Koga—if he has

managed to survive the rapid tum.

over of Nippon's war leaders—but

worse is yet to come. A powerful new

British ficet under Admiral Sir Bruce | |

A. Fraser, including ultramodern bat- yg

Heships and carriers, will fulfill Prime

Minister Churchill's promise of sea-

power to help America crush Japan.

Not to be confused with the British

force in the Indian Ocean, the Pacific

armada will be based on Australia,

and is expected to operate in close

teamwork with Fleet Admiral Chester

W. Nimitz and with General of the

Army Douglas MacArthur.

These, then, are the tools of Japa-

nese and Allied seapower—so far, a one-

sided picture. How about the men who use

them? Best-informed opinion ranks Jap

naval officers and men as the cream of the

Empire's armed forces, whose fanatical

courage makes overconfidence on our part

supreme folly. Even with their depleted

battle fleet, they may confidently be ex-

pected to pounce upon any advantage that

our extended lines and the slightest mis-

calculation may give them. Thoroughly

schooled In the unwritten “rule book” of

naval warfare, they perform at their best

50 long as everything goes according to

plan—as in their sneak attack on Hawaii.

But they have their weaknesses, too. Let

plans go awry, and the Jap totally lacks

Yankee initiative to grasp and exploit an

unexpected situation. And incompetence in

his high command, elevated to exalted posts

by the feudal system of caste rather than

for merit, has had an unfortunate way of

placing him in just such embarrassing posi-

tions. For six months, the Japs delayed

pressing home their temporary advantage

at Pearl Harbor—and then dispatched a

fleet of warships and troop transports to

seize Hawail.

They never got there, because they had

given us enough time to reorganize a fight-

ing fleet powerful enough to hurl them back

with smashing losses in the Battle of Mid-

way. Later, when our own amphibious

forces seized the offensive in the Solomon

Islands, Nipponese warships staged a whole

series of attacks in gradually increasing

strength. Why they failed to use their full

power at first can be explained only by the

inscrutable Oriental mind; as it was, we

were able to reinforce our embattled fleet

rapidly enough to repel every onslaught.

From that time until last October the

constant question was, “What will make the

Jap fleet come out and fight?” The answer

came when MacArthur invaded the Philip-

pines, with the obvious objective of taking

Manila and its strategic naval base astride

Japan's life lines to her southern conquests.

‘And the result was the Second Battle of the

Philippines—actually three battles in one—

where mighty battleships slugged it out

with shells in the rare and awesome spec-

tacle of a full-dress fleet action.

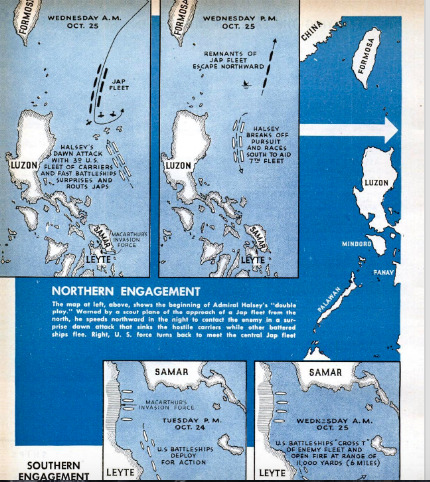

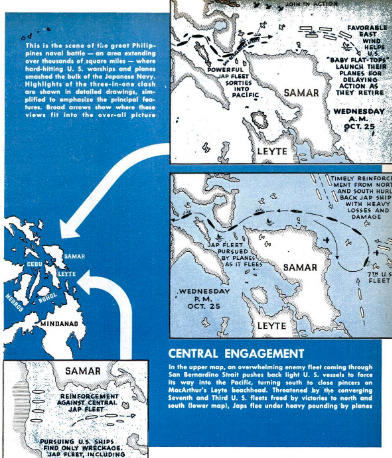

It was o desperate gamble, since it com=

mitted virtually all of Japan's warships, but

a better move than to wait until growing

Allied seapower sealed the gates of the Em-

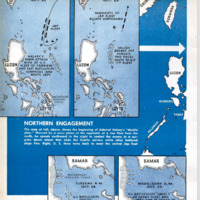

pire. From southern Asia outposts, a pair

of Jap fleets sought to thread the two main

passages through the Philippines and meet

in a pincers movement, where MacArthur's

supposedly vulnerable Invasion craft were

unloading reinforcements and supplies on

the {sland of Leyte. Meanwhile, a third Jap

fleet approaching from the north would pro-

vide support. If complete surprise could be

obtained, so much the better.

Wary of just such a move, however, Vice

Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid had posted

U. S. submarines as lookouts on the western

side of the Philippines, meanwhile guarding

MacArthur with his 7th U. . Fleet of bat-

tleships and lighter craft—supplemented by

Australian cruisers and destroyers. Prompt-

ly the subs detected the invaders and flashed

him warnings. Shortly after, a scouting

plane sighted the Jap fleet from the north,

and relayed a message to Admiral William

F. Halsey's U. S. Third Fleet of fast battle-

ships and carriers, roving farther to sea.

Cramming on speed, Halsey sped north

and intercepted the surprised Japs at dawn.

Before they knew what had hit them, their

four carriers were sunk—and the rest of the

ships, many damaged, turned tail. Reluc-

tantly abandoning pursuit, Halsey dashed

south again, in response to a report that the

U.S. defenders of San Bernardino Strait

were having their troubles with the central

Japanese force.

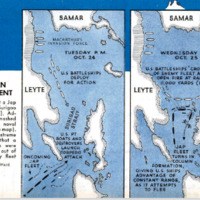

And so they were. Baby flat-tops on

watch in the channel found themselves con-

fronted with an overwhelming Jap fleet, in-

cluding two 45,000-ton battleships. Gallant

U. 8. destroyers braved mortal peril to lay a

smoke screen behind which the light carriers

retired—into a providential east wind that

enabled them to launch their planes on the

run. Circling back, the aircraft pounded the

oncoming Japs with such fury that they

made slow progress, although they overtook

and destroyed a few light American craft.

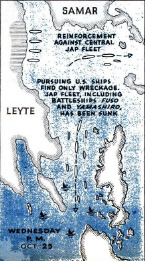

Forcing the passage into the Pacific, the

Japs started toward Leyte—and then mys-

teriously turned back and fled the way they

had come.

Evidently their commander, the Navy

concludes, must have received word of the

fate of the northern Jap force, and also of

the southern Jap fleet which had sought to

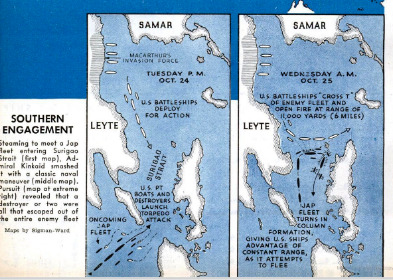

negotiate the Surigao Strait at night. Here

Admiral Kinkaid had laid a neat trap of

battleships and supporting forces.

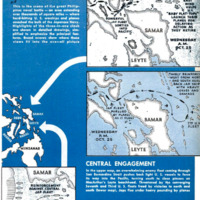

Dark silhouettes of the Jap warcraft sud-

denly stood out against a fiery sky as PT

boats, destroyers, and cruisers opened the

engagement. Then, with a thunderous crash,

the U. S. battleships spoke their piece.

Their commander had accomplished an ad-

miral’s dream by crossing the enemy's “T.”

or steaming across the head of his adver-

sary's battle line—which enabled him to

bring all his guns to bear while only the for-

ward guns of the enemy ships could reply.

To make things perfect, the Japanese

elected to escape by turning in column, or

follow-the-leader fashion. The first ship

gave the range, and practically every sub-

sequent U. §. salvo crashed home. Save for

a destroyer or two, every ship of the south-

ern Jap contingent, including the battleships

Fuso and Yamashiro, went to the bottom.

In the triple engagement, these two battle-

ships, four carriers, and six Jap cruisers

were definitely seen to sink, while 13 other

major warships were presumably knocked

out of action for from one to six months.

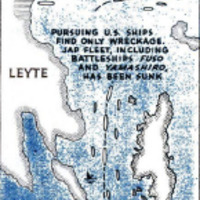

Old scores were settled in that and near-

by actions. Five battleships damaged at

Pearl Harbor, refitted and as good as new,

avenged themselves is the Surigao Strait

affair—the Pennsylvania, Maryland, Tennes-

see, California, and West Virginia. One

other battleship, the Mississippi, shared hone

ors with them.

-

Autore secondario

-

Alden P. Armagnac (article writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1945-02

-

pagine

-

90-96,228,232

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.17.21.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.17.21.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.17.26.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.17.26.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.17.36.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.17.36.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.01.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.01.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.17.47.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.17.47.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.11.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.11.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.01.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.01.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.06.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.06.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.11.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.11.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.21.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.21.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.27.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.27.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.37.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.37.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.44.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.44.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.52.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.52.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.58.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.18.58.png