-

Titolo

-

I ride "the beast"

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

I ride "the beast"

-

extracted text

-

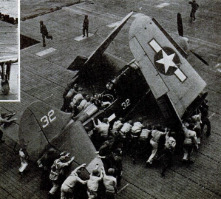

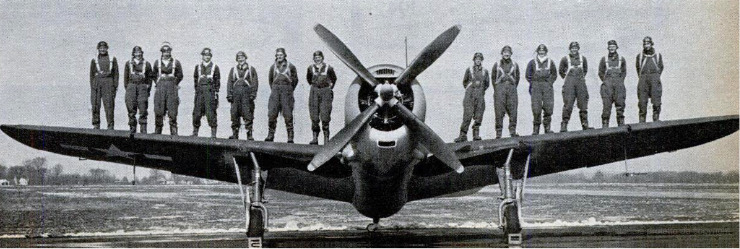

AT THE aft end of the carrier deck

some of our Helldivers sat packed

together, hunch-shouldered against the

wind like cattle sharing the warmth of

their collective bodies. Below, stored

in the cavernous hangar deck, were

other dive bombers, ready to be

wheeled quickly on the elevators.

We knew that it wouldn't be long

now. We were entering the combat

area of the western Pacific, bound for

what was to prove to be one of the

strangest engagements of the war.

Everything belied it. Some of the

pilots and air crewmen lolled in their

quarters or in the ready room. Others

monosyllabically played poker.

“Bombing One,” as our squadron

was called, had trained hard for this

hour. We had new-type dive bomb-

ers, faster, more heavily armed than

the carrier-borne bombers that had

been thrown at the Japs in the criti-

cal battles in the Pacific earlier in

the war.

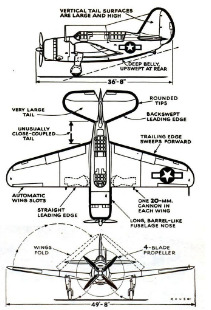

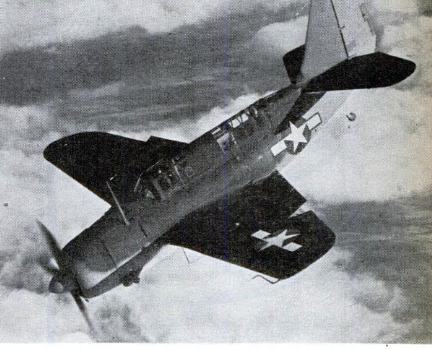

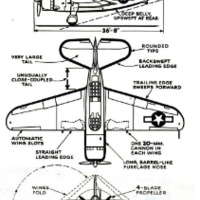

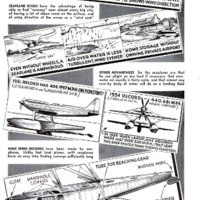

Our Curtiss SB2C Helldivers,

weighing some seven tons apiece,

were built to withstand the strains

of hard pull-outs and of bouncing

deck landings when our carrier—

which must remain unnamed—was

pitching and rolling. It is one thing

to put a plane down on an airport on

solid land, and another thing to do it

on a landing field that won't stand

still.

These planes were “the beasts.”

Where the term came from I don't

know, unless it derived from the big

fuselage (wholly enclosing the

bomb), the skyscraper fin, and the

engine with its barrel-like cowling,

which was as big as 10 wash tubs.

They had other attributes. They

carried a 20-millimeter cannon in

each wing, affording high firepower

against enemy planes and ground

installations. These were the first

cannon ever fitted to an American

dive bomber in the 16 years that the

Navy had practiced the art. They also

were the first to be mounted on a

carrier-borne plane.

In addition to the 1,000-pound

bomb carried in the belly, there were

two 250-pounders under the wings.

Protecting the pilot and rear gun-

ner were 150 pounds of armor plate.

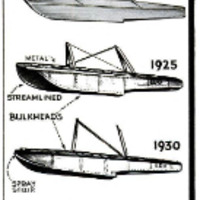

The Helldiver had been born in a

cattle barn on the Ohio State Fair

grounds at Columbus as the Curtiss

company pushed its manufacture in

temporary quarters while a new fac-

tory was being erected. The project

director, Raymond C. Blaylock—

who, by the way, had worked on the

FSC, the original Helldiver, the first

plane to be built specifically for dive

bombing when the Navy was evolv-

ing the technique between 1927 and

1930—managed hundreds of modifi-

cations dictated by Pacific battle ex-

perience.

My squadron knew what its job

was to be. The dive bomber and the

torpedo plane constitute the Navy's

one-two air punch. Their co-ordi-

nated attack is the only type that

bas been evolved with weight enough

to break

up enemy task forces. It worked in the Bat-

tle of the Coral Sea, at Midway, Guadal-

canal, and Rabaul.

On sea targets we would dive on anything

the Japs were foolish enough to put in our

sights. The fighters would strafe the decks,

then fly cover above us. Below us the tor-

pedo planes would sweep in and administer

the coup de grace after we had our targets

dead in the water.

Against land targets we would use sub-

stantially the same tactics. Land targets

were easier. They didn't move. There we

would get in the best licks with our wing

guns.

The first objective of the task force to

which we were attached was Saipan. The

Marines were to take Guam. This was D-

day minus 3, and our job was to soften up

the defenses. We also were to help neutralize

Jap air power in the area.

We hit Guam. Orote peninsula crawled

with Jap antiaircraft emplacements. They

were hard to see from the altitude at which

we ‘pushed over"-—that is, where we went

into a shallow dive. Usually it wasn’t until

we were halfway down that we spotted the

AA “winks.” Then we would have to go on

very low into a rain of automatic-weapons

fire to put our bombs where we wanted

them.

We used the cannon to start fires.

Our force pulled away and cruised north

to hit the Bonin Islands to neutralize the

Jap bases there and prevent interference

with our investment of Guam.

‘When we came back, a strange show was

going on. Without risk to their carriers

(they thought), the Japanese were launch-

ing hundreds of planes against us. Their

idea was simple. It was good. It just didn't

work. The Jap planes were to shuttle-bomb

—plastering our invasion forces and then

flying on to Guam. There they were to re-

fuel, rearm, and plaster us again.

Meantime, their carriers were to stand off

out of range of our fleet.

The double trouble for the Japs was that

our fighters shot down their planes prac-

tically as fast as they appeared, and what

few did get through couldn't use Guam be-

cause we had dive-bombed the airfield until

its surface looked like a Swiss cheese.

Somewhere, there west of us, was a Jap

fleet. We waited. Finally the orders came.

‘We didn’t know it then, but we were going

to participate in the First Battle of the East-

ern Philippines. It would be a long strike,

300 miles or so. The Helldivers had much

more range than earlier dive bombers. They

had more than 1,700 horsepower on their

noses, whirling three-bladed steel propellers.

But, even so, we ran the chance of losing

all the planes we launched. The point, of

course, was that the richness of the target

was worth the risk.

Bombing One pilots and gunners climbed

into their planes. Despite the size and

weight of the Helldivers, take-offs were

simplified by aerodynamic refinements. Out-

board on the leading edges of the wing were

“slots,” which go into operation when the

leading gear is lowered, assuring lateral con-

trol at low speeds. When the needle on the

air-speed indicator was at a dangerously

low point, a part of the leading edge of the

wing would pop out to channel an auxiliary

flow of clean air over the ailerons.

One by one we rolled down the length of

the deck, rendezvoused, and settled into for-

mation. Off to the right the planes of other

flat-tops were heading west.

It was a long flight. Presently two of my

planes got croupy engines and turned back.

That left 13.

Except for the blobs of cumulus clouds, it

was a perfect late afternoon. Here and there

the clouds obscured the sea.

Even before we flushed the Japs we knew

they had been found. The first elements of

our striking force relayed the news in code.

They were killing time, awaiting our arrival.

Then, of a sudden, our target was ahead

of us in plain sight. It was huge. It stretched

to the horizon, all around. There were flat-

tops, battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and

the inevitable “train” of supply ships. It

all looked peaceful enough as the afternoon

sun slanted on the water. Two of the ves-

sels, toy ships on a pond, were refueling.

Astern, flanked by two or three cruisers and

some destroyers, was a big Shokaku-class

flat-top of 30,000 tons. Its deck was bare.

For a dive-bombing pilot, this was smor-

gasbord.

“We're going after the big one astern,” I

radioed the leader of our torpedo-bomber

squadron. I glanced around. All of my boys

seemed O. K.

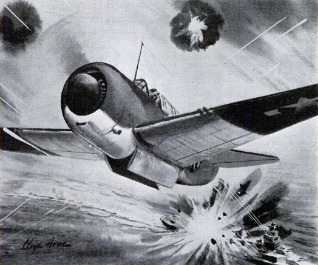

We nosed over at 15,000 and were doing

260 knots in our high-speed approach. We

opened the bomb-bay doors and pushed over

—steepening the dive—at 9,000 and opened

the diving flaps. The flaps, or air brakes,

are inboard on the trailing edge of the

wing. In position for a dive, they angle up-

ward and downward to form an elongated V.

The big bomb is carried internally, for the

first time in the Helldiver design, to stream-

line the plane and provide more speed. The

ship is fast enough to keep up with its es-

corting fighters, the Hellcat and the Corsair.

Antiaircraft guns began winking at us.

The flak floated past, reddish-brown, white,

and silver. AA fire comes straight at you,

and you wonder why it doesn’t hit you.

The carrier began turning. It turned

amazingly fast. That worried me. My plane

as yet was not in bombing attitude. I

wouldn't go into a 70-degree dive until I was

down to some 5,000 feet. I was leading the

carrier with my sight in an effort to lay the

bomb in the middle of its deck. I kept riding

the rudder pedals.

Dive bombing is a matter of estimation—

estimation of the wind, the speed and course

of the target, and the amount of time it will

take your bomb to drop from a given alti-

tude. You watch your altimeter, compen-

sating in your head for the “lag” it shows

behind your actual altitude.

There is little sensation to a dive. You

know you are picking up speed. The pres-

sure on your eardrums tells you so. Your

senses are alive to everything, even the

littlest item. The target keeps getting big-

ger. The whitecaps, which from upstairs

looked like white fluff on glass, begin taking

on motion.

The flat-top was trying to complete a cir-

cle. I steepened my dive. In a moment the

altimeter said “go.” I pressed the button,

automatically reaching for the manual re-

lease to make sure the bomb was gone.

With the next motion I closed the diving

flaps and bomb-bay doors and pulled out.

Pull-outs are a lot worse in fiction than

they are in fact. Your legs feel heavy for

a moment. Your sight sometimes dims, as

though someone had clipped you on the chin

with a boxing glove. Then it’s all over.

1 raced away, riding the rudder, hauling

and pushing on the stick to make my plane

a poor target. Things happen in slow mo-

tion in battle. I flew for what I thought was

a long time. Then I turned to count my

planes. Instantly tracers began outlining

the Helldiver in red. I resumed course, tak-

ing violent evasive action. Pretty soon there

were no more tracers.

I called up my squadron on the radio.

Fuel was low. It would take time to ren-

dezvous, so planes would have to return in

independent groups. Five of my planes

joined up with me. I wished we could wait

for the rest. We headed east.

It hadn't been a bad strike. Three mem-

bers of Bombing One had hit clean. My

bomb had been a near hit. The flat-top was

burning so well that the last two pilots to

push over decided not to waste their bombs.

on it. They attacked a cruiser.

Fire is the bane of the flat-top. If you can

penetrate the deck plates, the chances are

you will ignite the oil and high-octane gaso-

line stored below. Normally that stops it

dead in the water. A flat-top’s watertight

compartments make it hard for dive bomb-

ers to sink it, but the torpedo planes do a

nice job of finishing it off.

It looked as though the torpedo planes had

registered three hits on our target. Other

ships in the Jap fleet had taken a pounding,

among them a Kongo-class battleship. A

Hayataka-class carrier was sunk. Another

in the same class was damaged. A cruiser

and three destroyers were hit. Three tank-

ers were sunk, two others left burning.

Our planes flew eastward, throttled back

to conserve gas. The sun went down. Dusk

came, then night. The fuel needles crept

across the faces of the dials. It looked bad.

I kept rehearsing the sequence. of what to

do in a water landing.

My fuel needle wavered uncertainly at

the far corner of the dial. Now it was almost

on the little peg at the corner. This was it.

I waited for the engine to gasp and conk

out. And right then, as though in answer to

a prayer, we looked down on the home

hearth,

A lot of planes went into the water that

night. Some “splashed,” as Navy parlance

has it, short of the fleet on their way home.

Some milled around above the fleet, trying

in the melee to find their home decks, and

failing. Some landed on other carriers. |

The destroyers were everywhere, wet from

stem to fantail as always, pulling dripping

pilots and gunners aboard.

I happened to make our carrier—with five

minutes’ fuel left in my tanks. A cursory

roll call brought little response. I kept say-

ing to myself, “Well, it was a damn good |

squadron while it lasted.” I could think only

in the past tense. My pilots, my gunners,

my planes, were gone.

And then, one by one, destroyers began

drawing alongside and the men of Bombing

One began clambering aboard our flat-top.

Pretty soon I had half my flight, then three

fourths of it, and at the end of three days

every man Jack had returned. Our casual-

ties: one cut finger.

If all the awards I recommended come

through, the men of Bombing One are going

to have a lot of decorations on their blouses.

They deserve them. |

-

Autore secondario

-

Comdr. Joseph W. Runyan (article writer)

-

Eric Sloane (Illustrator)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1945-02

-

pagine

-

131-135,205-206

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.37.33.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.37.33.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.37.39.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.37.39.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.37.44.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.37.44.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.37.49.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.37.49.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.37.54.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.37.54.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.38.00.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.38.00.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.38.08.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.38.08.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.38.13.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.38.13.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.38.28.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.38.28.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.38.34.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.38.34.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.38.40.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.38.40.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.38.46.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-05 19.38.46.png