-

Titolo

-

The plane of tomorrow smells like an oil stove

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

The plane of tomorrow smells like an oil stove

-

extracted text

-

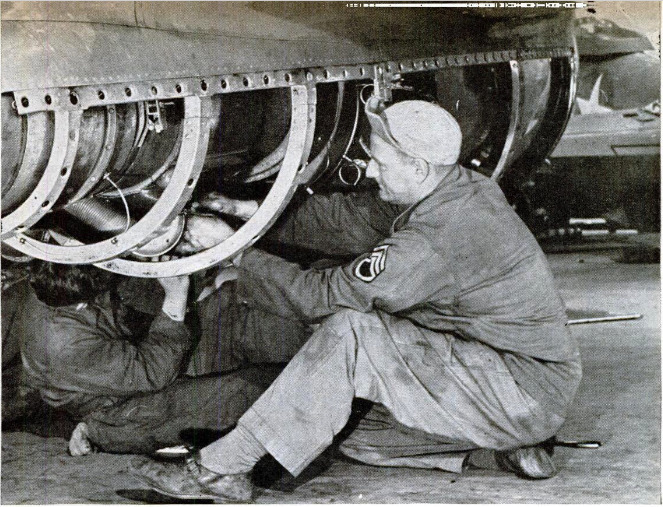

THE P-51 mechanic, curiosity and

perhaps a trace of contempt

written on his features, squatted

under the wing of the jet-propelled

plane and ran an eye over the flame

tube. Other mechanics were in-

stalling an engine in the jet job.

S/Sgt. Earl Kohler, in charge

of the project, glanced up.

“How does she look, Bill?” he

asked the Mustang man.

“Well,” came the considered re-

ply, “I'd call that a plumber’s

nightmare.”

That was early in the history of

jet propulsion in the Army Air

Forces. Since that day, mechanics

on conventional fighters and bomb-

ers have asked Kohler and his crew

a million questions about servicing

the jet plane.

“They want to know,” says Ser-

geant Kohler with some impatience,

“what wrenches we use. How long

it takes to pull an engine. How the

jet works. One guy even asked if

it uses fuel. All kinds of damn fool

questions.” }

Kohler, who operated a garage

for 15 years before he went into

the Army, was one of the first AAF me-

chanics chosen to work on the original

XP-59A jet plane while it was being put

through months of tests in the California

desert. After the project was revealed, he

‘was sent to Wright Field to keep the planes in

shape for training and further experiments.

“Every mechanic gets a funny feeling

‘when he first sees the jet job,” Kohler says.

“I remember what I thought. I said to

myself, ‘Hell, this thing won't fly. There's

not enough stuff.” But after the jet took off

a few times, I began to get the idea.”

Mechanics trained on Thunderbolts, Light-

nings, Marauders, and Fortresses—any of

our aircraft with conventional engines—

have learned to think of power in terms

of solid machinery, Kohler explains. In a

conventional engine everything is solid and

tight. Mechanics think in terms of com-

plicated wiring, ignition, gauges and cylin-

ders, elaborate fuel systems. Everything is

complicated.

“But in the jet plane everything is simple,”

Kohler says. “You put in six quarts of oil,

just like an automobile.”

The cooling system is just a couple of

oil jets which spray lubricant and air into

the two rotor shaft bearings. The oil is

standard hydraulic fluid 3580. The excess

runs down and forward into the accessory

section, and is returned by a small scavenge

pump. The system is cleaned by a Cuno

filter. The generator, fuel pump, and starter

are the only accessories carried over from

the conventional plane, and the ignition is

even more simple than the oil system.

There are only two spark plugs, located in

the No. 4 and No. 8 combustion chambers.

The other chambers are interconnected

and ignite from these two. After the unit

is started, combustion continues without

further assistance from the plugs. Com-

bustion is as steady as the flame of an oil

furnace. Plugs last as long in the intense

heat of the jet as they do in a conventional

engine. In the jet their spark gap is con-

siderably wider.

Kohler and his men work on the P-50A,

which must be classed as a training plane

in the jet field. Yet, with few exceptions,

their experiences would be applicable to any

jet aircraft.

“We use about a fifth as many tools,”

Kohler explains, “and maintenance of a

jejt plane is less than a fifth of what it is

on the other kind. As for the engine, it’s

so damn simple I can't understand it.

“Air comes in the front end, goes through

the compressors,

mixes with kerosene in the combustion

chambers, and is ignited. It blasts out

through the flame pipe, and that’s all there

is to it. How the hell that makes an air-

plane fly, I don’t know.”

Engineers, explaining the jet force which

drives a plane, have compared it to the

strong, sudden whip at the nozzle of a

garden hose when water is turned on full

force.

“Most mechanics are surprised to learn

that there are only eleven bolts holding the

engine in place,” the sergeant comments.

“And not very big bolts at that. In the

engine there are but two main bearings and

one shaft.

“I can pull an engine with an inexperi-

enced crew in 35 minutes, and four men can

pull both engines and install new ones in a

day. Where we used to spend five days

doing a certain job on a conventional plane,

we can do the same thing for a jet in a day.

Where other mechanics would use 25

wrenches for a certain type of job, we

generally use about five.”

All the equipment necessary for changing

a jet engine can be carried in the plane,

and this consists of a small wing holst and

frame, and a cradle to support the engine

when removed. Since the unit is so close to

the ground, no work stands are necessary

to reach any part of it.

Mechanics invariably ask about the jet

exhaust and want to know how close a

person can stand in front or behind the

engines, Kohler says. Most of them have

heard fanciful stories about women hav-

ing their dresses whisked off by the suction

of air going nto the engines. And there is

one story, widely told, of an officer who

tried to look into the rear end and got his

cap visor scorched off back to the eagle.

Kohler does not believe these tales, but he

does know a guy who stepped into the ex-

haust and was Kicked back 70 feet in fast

somersaults.

“Td say a person should keep at least

200 feet behind a jet engine when it is

blasting,” the sergeant recommends. “You

can stand closer without getting hurt.”

Once a flight is over, mechanics don’t

need to let the plane cool oft before begin-

ning work on the engine. By the time they

get the cowling off, the engine is cool

enough to be taken out.

Development of the AAF jet plane, one

of the best-kspt secrets of the war, took

place at Muroc, Calif, where Kohler said

he signed away his life every day. “Every

time turned around I was signing some-

thing, promising that I would keep. my

mouth shut.”

Even the commanding officers at an AAF

base near by did not know what was going

on inside the restricted area of the desert.

Pilots were forbidden to fly over it and no

amount of rank could get a curious officer

into the field. On several occasions, the fet

plane was seen smoking through the sky

and frantic telephone calls came from the

neighboring air base notifying jet crews

that a burning plane had fallen on their

field. The callers were politely thanked for

their concern.

One afternoon, when the experimental

plane was smoking heavily, the neighboring

air base called out its fire and crash equip-

ment and sent it clanging down the high-

way to the secret station. The crash wagons

pulled up at the main gate and demanded

to be let inside, drivers shouting that they

had the location of a burning plane.

Again, the guards were compelled to

thank them quietly and politely—and keep

the gates locked. On another occasion a

bird colonel became so curious that he drew

himself up to full height before the guards

and demanded to know what was going on

behind all the secrecy and mystery. A

security officer had to be called out to

pacify him.

“Colonel,” he said, “behind those hangar

walls is the hope of tomorrow. We are

coming out with a gadget that will revolu-

tionize the sewing machine.”

Perhaps the simplest function of fet

maintenance is servicing the plane with

fuel. This is no more involved than calling

the kerosene truck and filling up. The fuel

is thoroughly filtered to safeguard the

barometric fuel controls. These units do

what the regulator on a turbo-supercharger

does-—they maintain a constant power with

changing altitude. The engine can operate

on nearly any hydrocarbon fuel such as

gasoline, kerosene, alcohol, and even hair

tonic or brandy.

The jet engine has about 10 percent as

many moving parts as a reciprocating en-

gine and, since there is only a rudimentary

ignition system and no carburetor, there is

no elaborate mixture control, nor prop con-

trol, nor icing worries.

“You get all that in something they call

a plumber's nightmare,” Kohler says. “I

take them apart and put them back, and

I still can't find what makes them fly. It's

the airplane of tomorrow—and it smells like

an old ofl stove.”

-

Autore secondario

-

Edward T. Wallace (article writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1945-03

-

pagine

-

70-71,224,228

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)