-

Titolo

-

You can't fly without airfields

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

You can't fly without airfields

-

extracted text

-

THREE times in 150 years of United States

history, transportation has been revo-

lutionized. First came the development of

canals and other inland waterways; then,

the construction of our great railway net-

work; finally, the building of an incompar-

able highway system. Each of these in

turn brought profound changes in the Amer-

ican way of living.

Now we are at the beginning of a new

era in transportation. We are ready to

broaden and deepen the foundations for

what may well become the world’s finest

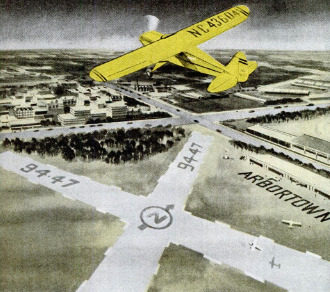

GOOD ROADS made the Auto Age come teu. Onl good Land:

ing fields—and plenty of them, everywhere—will make the.

Air Age come true.

Go back a littlo—to 1920, just after the last war. We had 339,000

mills of surfaced streets, roads, and highways. On these we drove

9,000,000 motor vehicles. By 1941 we had spent over forty billion

dollars for road building and had 1,697,000 miles of surfaced

streets, roads, and highways. They carried 34,000,000 motor ve-

hicles. And total travel was up 534 percent.

Landing fields are even more important to lying than good roads

are to motoring. You can't ly anywhere unless you can land.

The extent to which you and your town are going to share in the

benefits of the Air Age depends largely upon the personal interest

that you and your fellow citizens take in providing adequate land-

ing facilities—landing strips or Mightstops, airparks, air harbors.

Almost everyone is going to fly—in private planes, in air taxis

and air buses in transports. A town with good landing facilities

Sell grow with the Air Ago ... attract residents who are progres-

sive, successful, Forward-looking ... gain tho business advantages

and added employment that go with the development of a gigantic

new industry ... expand its community activities, will be tied

into the whole world-wide postwar system of air transport.

‘What finer tribute could any community make to the memory

of the men and women who are sacrificing their lives in World

War II than to build a victory landing field and dedicate it to

them? It would be a living memorial, better than any monument.

To combat postwar unemployment, many states are already

setting aside vast surplus funds for postwar improvements, part

of which should be earmarked for landing fields. And the Federal

Government, i it follows recommendations in the $1.250,000,000

“National Airport Plan” of the Civil Acronautics Administration,

mow before Congress, will share the costs with states on a 50-50

basis aa in the Public Roads program.

Now is the time, therefore, to use your influence in your own

community to plan a landing field and, if posible, acquire the

land. Only in this way can you—and all your fellow citizens—

share fully in the coming Air Age.

We should be glad to have your comments, suggestions, and

questions on this subject, Address the Aviation Editor, POPULAR

SCIENCE MONTHLY, 353 Fourth Avenue, New York 10, N. Y.

"THE EDITORS

facilities for travel in another medium—

the air.

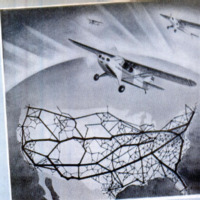

Both for the big commercial airliners,

linking cities and continents, and for priv-

ately owned airplanes, giving personal wings

to millions, airports, “airparks,” and other

types of landing areas will be built in each

of the 48 states.

The bill: $1,250,000,000.

The goal five or ten years from now:

6,000 landing areas, or one within reach of

every American community with a popula-

tion of 1,000 persons or more.

There is a close parallel between railroad

and highway construction and the building

of places where airplanes can take off and

land. The major airport, with its multiple

runways and instrument landing equipment,

is to the transport plane what a track and |

a block-signal system is to the railroad

train. The airpark and subsidiary landing |

facilities are to the private plane what the

well-groomed highway is to the automobile.

The inland waterway was the backbone of

the United States domestic transportation

system in the first third of the nineteenth

century. The golden age of railroad con-

struction was the last half of that century. |

The extraordinary expansion of America's |

highway network occurred after the First |

World War.

Today the aviation counterpart of rail-

road and highway construction is a tele- |

scoped project. Landing areas to give both

the airliner and the personally owned plane

maximum utility will be built simultane-

ously.

And, interestingly enough, just as the

construction of railroads and highways had

a pronounced effect on the ability of the na-

tion to defend itself against attack, so will

landing facilities for airplanes contribute

to national defense.

When the war is over we are going to

need a lot of places where airplanes, of both

the transport and personally-owned types,

can take off and land.

Official Washington anticipates a twenty-

fold increase in the number of licensed air-

planes by 1950. On the basis of less than

25,000 nonmilitary aircraft of record before

Pearl Harbor, that would mean a half mil-

lion private planes and commercial trans-

ports. Other estimates run well beyond the

million mark for the end of the first decade

after the war.

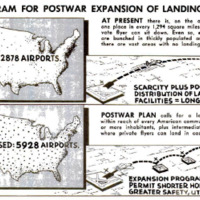

Today there are good landing facilities for

only a fraction of either number.

We have, in fact, less than 3,000 fields,

exclusive of those built for military opera-

tions. Of those, 740 are suitable for air-

liners.

Only 291 communities in the United States

are served now by the scheduled air-trans-

port system. Almost 6,500 with popula-

tions of 1,000 or more have no service.

Government experts estimate that within

a decade after the war 20 million passengers

will ride the air lines annually as against

a fifth of that number in 1941.

The number of intercontinental commer-

cial airliner flights will be increased sharp-

ly. Planes will leave not only from the

seaboards but also from cities in the inter-

ior of the country. It is a shorter distance

from Chicago to Moscow than it is from New

York to Moscow, for instance.

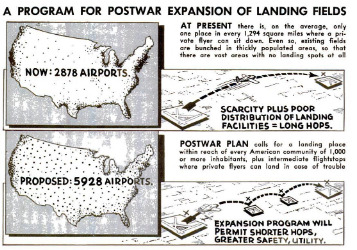

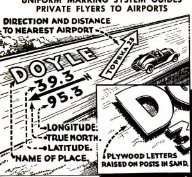

In most parts of the United States the

private pilot, riding cross-country, keeps a

worried ear attuned to the throb of his en-

gine and a bilious eye on the weather, be-

cause the spots where he can make emer-

gency landings are few and far between.

On the average, he has a place to sit down

only once in every 1,204 square miles.

Even that figure is misleading, because

landing fields are bunched around the more

populous areas, leaving the great open

spaces arid of facilities. Moreover, fully

half the existing fields are indifferently

maintained. In bad weather they are mud

holes. They are badly marked. A pilot

needs a telescope to spot them from the air.

We are going to have a lot more places

where airplanes can take off and land. More

than 60 percent of the money to be poured

into standard airports and lesser landing

facilities is earmarked tentatively for im-

proving ports that can be used by airliners.

Here is a hypothetical case history of what

expanded air-line service would mean: Two

cities of 100,000 population lie 600 miles

apart. Between them, evenly spaced, are

five communities of 25,000 each. If a trans-

port plane makes a stop at one of those five

communities on its flights between the two

Dig cities, traffic between the terminals in-

creases by 70 percent. If two stops are

made at intervals of 200 miles, the traffic

increase is 160 percent. If stops are made

at all the intermediate communities, the

traffic between the two terminals increases

sixfold.

The rest of the money earmarked for

landing-field construction and improvement.

will go to the private flyer. Counting all

the projects in the long-term plan, he will

have a minimum of 5,000 ports. Possibly,

with the inclusion of intermediate landing

“strips,” he will have as many as 6,000 to

10,000 stopping points. If he had 8,000, he

would enjoy a landing area in every 372

square miles.

The nation’s smaller communities will

benefit most from the airport program. Of

the new airports planned, only 150 will be

built in cities of more than 50,000 popula-

tion; only 59 in cities of between 25,000 and

50,000; but 515 in cities of 5,000 to 25,000,

and 2,326 in towns of less than 5,000.

What neither industry nor Government

knows is just what America will have when

the building project is complete. Airplane

design, as to both size and performance,

which largely dictate airport design, is in a

state of flux. The commercial air lines are

only guessing about what kind of equip-

ment they will need a decade, two decades,

from now. Manufacturers are only guess-

ing about how many people will buy planes

for their personal use.

Will the transoceanic airliners

be behemoths of 200 tons gross

weight, as compared with today's

40-ton standard versions? Will the

domestically used transports carry

30 passengers or 100, and on hops

of what length? How many coast-

to-coast nonstop or one-stop sched-

ules will be needed as against

“local” schedules stopping every 50

or 100 or 200 miles? Will the take-

off and landing speeds of transport

planes require surfaced runways a

mile in length, or a mile and a half,

or two miles?

Will private-owner aircraft be

standardized in the conventional

fixed-wing design, or will they be

largely of the whirling-wing type

like the helicopter and the Auto-

giro? If of the fixed-wing type,

will better engineering progressive

ly reduce their take-off and landing

runs,

encouraging a shrinkage rather than an ex-

pansion of landing areas? If whirling-wing

craft—which can take off straight up and

land straight down—are first in popularity,

will communities be dotted with relatively

small fields, rather than a few larger ones?

To all these questions only the public can

answer. Any air line or manufacturer would

give a year’s earnings to get those answers

in advance. The trouble is that the public

itself doesn’t know them yet.

Using the only lamp by which man’s feet

are guided—the lamp of experience—manu-

facturers, air-line executives, and private

flyers are counting on compromises in ar-

riving at airport sizes and runway lengths.

While at least two manufacturers are

planning the construction of airliners to

accommodate 100 passengers or more, which

‘would require 10,000-foot runways, Charles

I. Stanton, Deputy Administrator of Civil

Aeronautics, says:

“Twenty- to 60-passenger airplanes are

going to be the backbone of our domestic

air-transport system for some years to

come, because they can furnish long-distance

travel with intercity bus-schedule frequen-

cies. Edward Warner, of the (Federal) Civ-

il Aeronautics Board, concludes that 50-

passenger airplanes are likely to be the best

for transatlantic services also.”

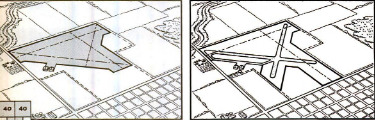

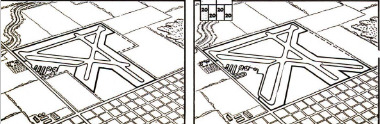

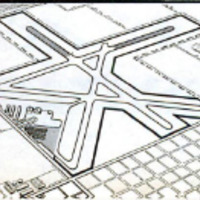

Cities, anxious to be on the main line of

air traffic, are in a quandary. It is axio-

matic among airport engineers that if you

double runway lengths, vou require four

times as much over-all area in an airport.

They state, too, that if the terminal is placed

in the center of the airport, with runways

sticking out like the spokes of a wheel—a

favorite current design of some of the plan-

ners—you again quadruple the size. That

automatically pushes the airport farther

from town. "Great expanses of land rarely

are available at the city limits except at

prohibitive prices.

So compromises will be made. A few of

the big cities will have super-airports with

a few paved runways nearly two miles in

length. Very likely these will be for air-

liners engaged in intercontinental flying.

There will be hundreds of terminals with

runways no more than a mile in length for

intercity schedules.

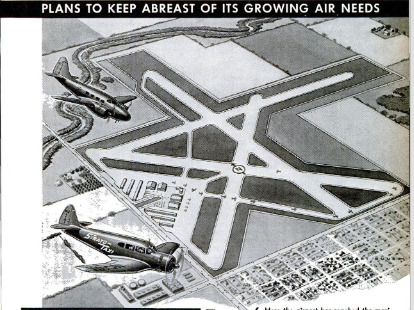

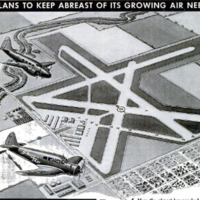

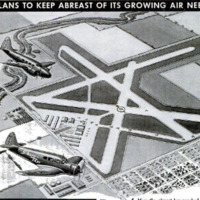

Typical of the outsize airports to come is

Idlewild, under construction for New York

City. It will cover 4,057 acres, contain a

dozen paved runways and, when complete,

will be able to handle a theoretical total of

5,760 take-offs and landings each 24 hours.

Chicago has under consideration a vast air-

port covering 3,600 acres fronting on Lake

Michigan.

Of the first half dozen runways to be built

at Idlewild, by the way, two will be 10,000

feet long, and the other four will scale down

to 8,200 feet, 7,500, 6,500, and 6,000 (2,000

yards).

For airliner operation, airport saturation

depends not on the size of the landing area

but, instead, on the number of schedules

that can be handled hourly. That, in turn,

depends on the number of planes that can

be dispatched and landed under instrument-

flying conditions—when fog, snow, or heavy

rain lowers the “ceiling” and reduces visibil-

ity. That, finally, depends on the installa-

tion of parallel runways and the refinement

of radio aids.

Parallel runways now permit only six de-

partures and as many arrivals an hour in

instrument weather. Engineers are hope-

ful of boosting that to 30 in and 30 out—or

one movement per runway each two min-

utes—in the next few years. In clear weath-

er a movement of 70 planes an hour on one

runway is considered feasible.

Just what the private pilot will have in

landing facilities in the postwar years will

depend in part on demand, in part on the

vision of the men planning for the future

of private fying. The utility of the private

plane hinges on that hoary conundrum:

Which came first, the chicken or the egg?

Should private flying create the demand for

landing areas, or should landing areas

create the demand for planes?

The national aviation planners are bank-

ing on an increased demand for planes if

the landing areas are created first.

Very likely several hundred of the larger

airports ultimately will be closed to priv-

ate flying. Even now the big terminals dis-

courage the patronage of the private pilot

by charging him landing fees. (At New

York City's La Guardia Field, for example,

the minimum charge for a private-plane

landing is $2.50.) They don’t welcome priv

ate planes for the same reason that a rail-

road terminal does not plan for, or welcome,

the business of the private motorist.

In the postwar years the landing areas for

the private pilot will have all the landscaped

beauty of the express highway. They will

cluster around the perimeters of the big cit-

ies, or, indeed, be built right within the city

limits, within easy reach of the business dis-

trict. They will be as much a part of the

smaller community as the playground or

the town square.

Nor will they be limited to that. Inter-

‘mediate landing areas, probably to be known

as “flightstops,” will be sprinkled liberally

throughout the country. In the form of T's

or L's to provide take-offs and landings for

all wind directions, they will be built at the

intersections of major highways, and more

than likely be adjoined by the counterparts

of the automobile tourist camp. There the

itinerant pilot can land in the face of a

storm front or tarry overnight.

Col. Earle Johnson, national commander

of the Civil Air Patrol, Army Air Forces

auxiliary, suggests that both for the future

of civilian flying and for the military secur-

ity of the nation landing facilities can well

be made postwar victory projects—taking

the place of “useless” war memorials.

The national airport program is identified

inseparably with national defense. Air-

ports mean facilities for moving armies

from one border of the country to the other

by air overnight. They mean the opportun-

ity to concentrate fighting and bombing

planes at any point that may be threatened.

They mean mass flying, and mass flying

means a backlog of men who will know at

least the rudiments of aviation if they must

be thrown into military training in another

emergency.

Tomorrow's airport-airpark-airstop-air

harbor network gives promise of crystalliz-

ing what airmen have been talking about

almost since the turn of the century—mass

three-dimensional travel.

-

Autore secondario

-

Devon Francis (article writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1945-03

-

pagine

-

74-81,211,212

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.10.14.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.10.14.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.10.22.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.10.22.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.10.29.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.10.29.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.10.35.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.10.35.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.10.42.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.10.42.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.10.50.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.10.50.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.10.56.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.10.56.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.11.03.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.11.03.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.11.10.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.11.10.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.11.15.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.11.15.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.11.03.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.11.03.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.11.29.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.11.29.png Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.11.36.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-10-07 12.11.36.png