-

Titolo

-

Zoom boats sock like battleships

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Zoom boats sock like battleships

-

extracted text

-

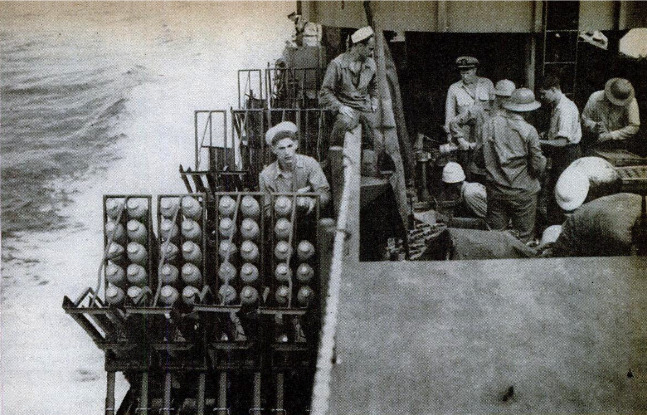

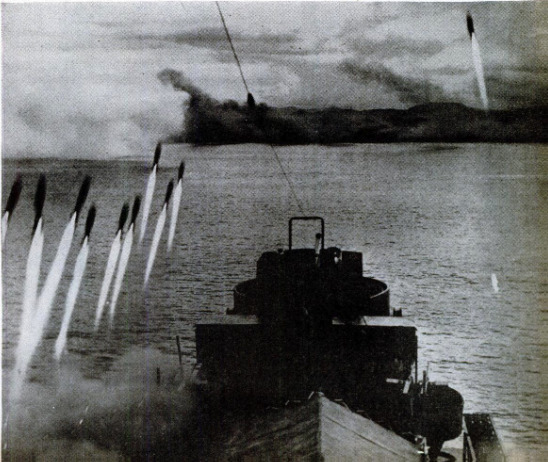

ORANGE flames flash and smoke puffs

along the decks as American landing

craft approach hostile shores. But these jets

of fire in the dawn's dim light cheer the men

about to land, for they mark the departure

of a salvo of rockets to clear the coast of

Japs.

Each rocket whooshing forward will hit

like a 105-millimeter shell, and hundreds of

rockets now can be shot electrically from

the tilted crates along the sides of a single

landing craft. All told, the short-range

salvos from one rocket-firing craft may be

a fourth greater than the firepower of two

of our modern, New Jersey class, 45,000-ton

battleships.

Rockets are an ancient weapon; they

stopped Kublai Khan in the thirteenth cen-

tury. But they have been improved so

greatly so recently that the Navy spent

10 times as many million dollars to produce

them in 1944 as in 1943. And now, more

huge rocket factories are being built—to

supply the armed forces with more mil-

lions of dollars’ worth of rockets per month

this year than were ever made before per

year,

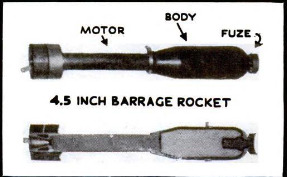

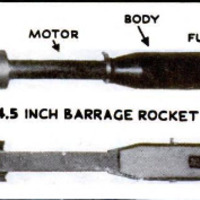

The beach-barrage rocket that is clearing

the way for American invaders in the

Pacific weighs a little more than 15 pounds.

Its body is 4.5 inches in diameter and is

loaded with a high explosive. On its nose

there is a tiny wheel that is whirled by the

wind when the rocket swishes into the air.

This arms the fuse, which touches off the

explosive payload in the body of the rocket

when it strikes upon the enemy’s ramparts.

Behind the explosive head of the projec-

tile is a “motor” consisting of a long, nar-

Tow tube of propellent powder and an elec-

trical wiring system. Current to start this

motor is supplied by batteries, charged by

generators fed by the ship's engines. Con-

tact between these batteries and the wiring

within the rocket is made by a little wire,

known as a pigtail, which extends from the

rocket’s tail into the launching rack.

When current flows into the wiring sys-

tem through the pigtail, the propellent pow-

der is ignited at the end near the payload.

The fire travels backwards through this

tube of powder. It burns more slowly and

steadily than ordinary gunpowder and emits

fiery gases. These escape through a nozzle

in the tail and thus drive the rocket for-

ward.

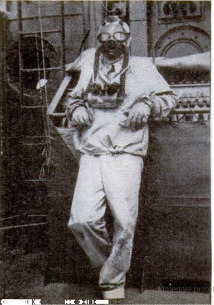

There is a loud hiss, rather than a boom,

when a rocket is fired. The tail jet is 50

hot that men take cover before launching

these rockets and wear asbestos suits when

working with them. But this bright, yellow-

ish, torchlike flame lasts only long enough

to lift the rocket well into the air. It ceases

before the projectile begins its descent to-

ward the target.

The effect on the enemy is similar to

that of heavy mortar fire. Rockets do not

have the velocity or high degree of accuracy

of artillery. But

they can be fired so that each salvo overlaps

a previous one. Targets may be determined

by using ranging rockets. And the blast

effect and fragmentation from a barrage of

bursting rockets can be employed to make

the area where men are about to land too

hot and lively for the foe to linger there.

Secondary fortifications, including mines,

wire, machine-gun nests, and shallow pill-

boxes can be virtually eliminated. Even men

protected by large, strong fortifications can

be temporarily stunned by a rocket bom-

bardment.

The 4.5-inch rocket, moreover, is only one

of several calibers now in use. The smallest

is called a SCAR, sub-caliber aircraft rock-

et, and is only 2.5 inches in diameter. The

largest is five inches in diameter. Recent

developments, however, have made it possi-

ble to produce bigger rockets, aim them

more certainly, and use them at longer

ranges. For example, it has been suggested

that an automatic computing device similar

to the electronic bombsights now in use

might enable a fighter-plane pilot to launch

rockets at a target with greater accuracy.

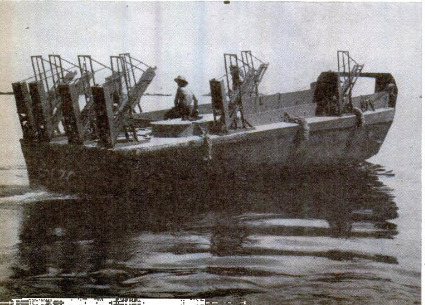

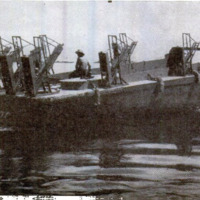

Since there is no recoil, the apparatus

from which rockets are launched can be

lighter and much simpler than a gun. The

US. Navy put rocket launchers on its

LCS (8), landing craft, support (small),

while the British were putting them on their

LCT (R), landing craft, tank (rocket).

Some of the latter craft were turned over to

this country more than a year ago. After

careful tests, Navy authorities ordered more

of them converted to American designs and

specifications with the utmost speed. Until

recently, these vessels were definitely hush-

hush.

Meanwhile, rockets were used with sensa-

tional success on the Navy's LCI (G),

landing craft, infantry (gunboat), in the

Pacific. A single LCI skipper estimated that

his craft fired 1,000 rockets into the beaches

of Guam.

‘Washington authorities report that the

Japs have made comparatively little use

of rockets. But American officers have

found that invasion casualties can be re-

duced by using more rockets.

The Army is directing the production of

propellent powder, and the Navy is in

charge of assembling, loading, and testing

rockets. Homec-front workers are being

asked to turn them out faster, in greater

quantities, to save American lives.—VOLTA

TORREY.

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1945-03

-

pagine

-

82-84,232

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)