-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

A-20 Bombers Squadron Overview

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Speedy, Hard-Hitting, Bombers Form The Porcupine Squadron

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

YOU may talk all you want about your

heavy bomber, which comes in from

almost incredible distances and un-

packs its punches from invisible altitudes.

Nobody but its own crew is ever going to

love it. Nobody ever loves the fighter with

a bicycle, who dances around the corners

of the ring and lets loose his blows by re-

mote control.

This story is about a lightweight. It

hasn't been ballyhooed nearly as much as

the big boy, but it's the fastest, toughest,

bloodthirstiest infighter on wings.

With its shoulders hunched forward in a

Jack Dempsey crouch, it sails right in and

mixes it up on the enemy’s own ground,

with kidney jabs and rabbit punches. When

the American soldier comes personally to

grips with the enemy, this plane will be

right in there with him, bombing from 75

feet above ground, biting in the clinches.

The American soldier is going to love it,

as an intimate comrade in arms. The British

love it already, for the enemies it has

slaughtered.

In its already long record of homicidal

wickedness, this ship has four aliases.

Americans know it as the DB-7 and the

A-20A. The British call it the Boston and

the Havoc. It has as many specialties as

it has names, but whatever may be the job,

it always has the same fingerprints and

sharklike killer's mug. It is the Douglas

light bomber.

Designed as a bomber, weighing 91% tons

loaded, this twin-engined plane attained its

first great usefulness as a fighter, and a

night fighter at that. It first reached Eng-

land at a time when the British were con-

cerned, not with the ground-straf-

ing of troops, but with the inter- |

ception of the night bombers which

were destroying London. The

Night Interceptor Command took ;

the ship, blacked out its goldfish- |

bowl nose where the bombardier

sat, and filled the space with the |

greatest arsenal of cannon and i

machine guns ever put into a fight-

ing plane. They shrouded the |

ship's exhausts with long tail pipes

to hide the spitting flames and fit-

ted it with secret devices for scent- |

ing enemies at night. They cut a

ton off its loaded weight. They |

called this modification the Havoc. |

Soon it was knocking down night

bombers as they came in over the |

Channel, getting the reputation for |

destroying more of them than any

other interceptor. Then a still |

more aggressive job was devised

for it, described as “night intru- |

sion.” The Havoc slips over to the

Continent, using its 1,200-mile |

range, and lurks near a Nazi air-

drome like a weasel around a hen |

coop, picking off the bombers as |

they start out for England or come

home to roost.

To the American builders, this

metamorphosis of the DB-7 was a |

surprise and a delight. The manu- :

facturers put it into mass produc- |

tion, hopped up its power. It was

one of the very first ships to get double-

row engines. The British aeronautical press,

never inclined to overpraise American

planes, was permitted to report that Havoc

III, the latest version, had a top speed of

380 miles an hour. This would make this

relatively heavy ship faster than the Hur-

ricane, right in the Spitfire class.

Meanwhile the American, light-bomber,

version of the ship was christened the Bos-

ton by the R.A.F. and was found useful not

only for attack work by daylight but also

for the highly important jobs of observation

and reconnaissance,

Naturally the success of their flying pro-

tégé in the night life of the Continent tend-

ed to cramp the style of the light-bom-

bardment men in the U. S. Air Forces. They

couldn't get as many ships as they wanted,

but they had enough of the A-20 to try it

out thoroughly in their own tactics, a tech-

nique of attack which they had been de-

veloping for the last 20 years. This is a

type of low-down assault so utterly differ-

ent from the uses of the Havoc that it is

amazing for one ship to be useful for both

purposes. But the A-20 turned out to be

an ideal ship for contour flying, which the

pilots themselves call grass-cutting or

skipping through the dew.

Let's take a look at the A-20. It is a

shoulder-wing monoplane, with its two ra-

dial engines in two big underslung nacelles,

which taper back far beyond the trailing

edge of the wings. The big wheels of the

tricycle landing gear retract into these

nacelles. The narrow fuselage projects for-

ward into a nose almost as long as the tail

which leads back to an unusually high fin.

The pilot's single cockpit is forward of the

propellers and the bombardier’s transpar-

ent compartment occupies the nose. The

gunner (or gunner and observer) can work

both from a rear cockpit and from an open-

ing in the plane's belly. The ship has a

span of 61 feet 4 inches and is 47 feet 7

inches long. Loaded it weighs 19,500

pounds.

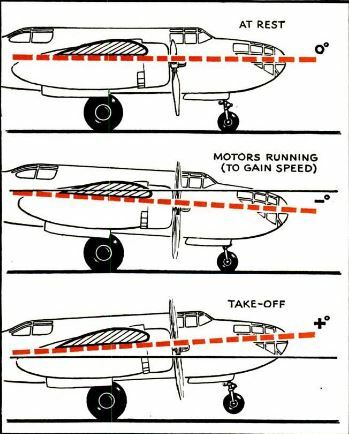

Even sitting on the ground, the plane has

a sporty, aggressive look, as though its

shoulders were hunched forward ready for

a fight. Studying this, vou realize that its

wings are tilted, not up, but downward.

They have what the aeronautical engineers

call a negative angle of attack. Speeding

down the runway on the take-off, the plane

has no immediate impulse to fly, but rather

presses its nose down, taking up all the

slack in the shock absorber on the forward

wheel of the landing gear. To start it flying,

the pilot has to pull back on the stick, push-

ing the tail down. To cut down wind resist-

ance and increase speed, this ship takes ad-

vantage of a remarkable fact of aerody-

namics: that a wing with unsymmetrical

camber (bulging on top and flat on the

bottom) can lift without being turned up

into the wind, can lift even when it is

cocked down. This peculiarity makes neces-

sary a very high landing speed. The A-20

is a hot ship.

But the exciting thing about this ship is

the way it is used, by the American light

bombers as well as by the British night

fighters. The A in its name stands for “at-

tack,” and the flyers who use it were known

officially until two years ago as attack

squadrons. Their tactics, on which these

squadrons have been working for the last

20 years, are to fly in upon an objective at

such low altitude that they practically skim

the treetops. By using parachute bombs

which give them an instant for escape, they

can blast troops from an altitude of only

75 feet and be safely out of the way before

the explosions. Otherwise, they would be

felled by their own bombs.

The A-20A flyers of the 3rd Bombardment

Group (Light) pride themselves that, fol-

lowing the contours of the land at 75 feet

altitude, . they can go to an objective 300

miles away and bomb it within a half min-

ute of a specified time. Plenty of flyers in

this outfit have nicked the tops out of pine

trees in the course of their training. During

the Louisiana maneuvers an A-20 pilot

sheared his plane through a cluster of five

high-tension wires, without damage to any-

thing but the power line.

The surprise and terror of an approach

by a flight of these planes, flying more than

300 miles an hour so close that you can

almost touch them, is something which

must be seen and heard to be appreciated.

When I first saw them, a flight of eight

A-20's, followed by Navy Grummans and

P-39 pursuit ships, came in suddenly and

low over an air field in North Carolina.

There were 12 press photographers there,

but so fast and furiously did those planes

arrive and depart that not a photographer

got a shot at them. It would have been

even more difficult to catch them with a ma-

chine gun.

Imagine a road through the jungle,

streaming with Japanese troops. Suddenly

there is a roar of approaching planes, but

before the direction of approach can be

identified, the planes appear over the tree-

tops only a few hundred yards away, travel-

ing 160 yards a second. There are three of

them, one for the center, one for each side

of the road. Before a machine gun can be

aimed, they are over and past, each drop-

ping a bomb every ten yards for 1,000

yards. By the time this article gets into

print, it may not be necessary to imagine

this scene of destruction. It may very well

have happened.

Recently I flew on a mission with one of

these squadrons. Out of consideration for

local residents they were flying at an alti-

tude of 500 feet or above, but over a stretch

of uninhabited country they came down

close over the treetops and showed me what

hedge-hopping is really like. Sitting up in

the transparent nose of the lead plane,

traveling better than 300 miles an hour,

over treetops which often were no more

than 20 feet below, following the hills up

and down like a skier—it was an experience

which can only be stated, not adequately

described.

Flying as a squadron this way, we were

almost proof against attack. Ground ob-

servers’ more than a few hundred yards

away could not see us. Often we were down

in a ravine with ridges of land rising on

cither side. Pursuit planes could not get

at us. The A-20 has a critical altitude of

1,000 feet above sea level; that is, its en-

gines perform best when right down by the

ground. Most pursuit planes are built to fly

above the clouds, and they will burn their

engines out if they fly at wide-open throttle

close to the ground. To get at us, at our

speed, fighter ships would have to dive.

And when a fighter ship pulls out of a

power dive, it mushes or squashes through

the air for a long distance before its wings

finally support it. A plane diving at us

would have a very good chance of crashing

into the ground. Assuming that fighter

ships did get down close to our level, they

could not get under us. And if they

came in over us they would confront a

close-flying phalanx whose back was a

bristling nest of machine guns, as dan-

gerous to approach as a porcupine.

The A-20 can also be used for level

bombing at higher altitudes, and even

that does not exhaust its usefulness.

It's a lot of plane in one package.

A regular little death-dealing sweet-

| heart!

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Hickman Powell (Article Writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1942-05

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

82-88

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

References (Dublin Core)

-

DB-7

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Roberto Meneghetti

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 5, 1942

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 5, 1942