-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

The Iron Horse Saves the Day

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

The Iron Horse Saves the Day

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

TALK all you want about airplanes

and electronics and motor transport

—the part of this war effort which really

rates a shout of amazement is the role

played by the American railroads. The

iron horse, which plowed the plains and

spanned the mountains, was not what he

used to be. For the last 20 years he had

been getting creaky at the joints. To

this Buck Rogers generation, millions of

whom had never even ridden on a train,

it seemed that he was inevitably doomed

to go out to pasture. But here is the old

horse now, snorting in the traces, haul-

ing bigger loads and faster than anyone

dreamed possible—Ileast of all the rail-

road men who are making him do it.

With fewer miles of road than they

had in 1918, with fewer employees, with

20,000 fewer locomotives and 600,000

fewer freight cars, the railroads of

America in 1942 moved two thirds more

ton-miles of freight than in 1918, and

in 1943 are moving twice as much. In

the first three months of this year, their

passenger traffic, which had slumped off

to a trickle in the 1930’s, was virtually

double what it was in the corresponding

period of 1918. And this, mind you, is

the accomplishment of a transportation

system which in 1918 was almost at

its peak and for two decades after that

had been taking it on the chin from the

truck and bus competition of the motor age.

‘We Americans of the motor age, indeed,

have only God and the railroads to thank

for the fact that we avoided national disaster

in 1942. Pearl Harbor was bad enough, but

when the U-boat packs fell upon our de-

fenseless oil tankers on the eastern seaboard,

they were striking much closer to the actual

vitals of the country. The whole industrial

Northeast was dependent on gasoline, and

the devastating success of the submarine

was cutting off that supply.

It was the railroads that came to the

rescue and averted the collapse of motor

transport. A fleet of 70,000 old tank cars—

used by the oil companies for odd jobs of

storage and short hauling—were put to

work, hitched into solid trains, and shuttled

back and forth across the country on fast

daily schedules as precise as passenger serv-

ice. Railroad men had been laughed at

when they first thought they might be able

to move 200,000 barrels a day in this fashion,

and soon it was proved how wrong they

were. For by this last summer the old tank

cars—stopping occasionally to get new wheels

—were moving five times that much!

The East still starved for gas. But that

was because the railroads had been so suc-

cessful that the Army and Navy dared to

draw on eastern gas for their fighting supply.

While this battle of oil was being won, the

loss of Malay rubber to Japan threw another

great burden on the rails. We have man-

aged to get by on our tire supply, because

railways have absorbed the great expansion

of traffic that would have been on rubber.

Transportation is a fundamental necessity

in any war. Sea transport, because it is

under attack, and air transport, because it is

new, have had the spotlight; but the rail-

roads have handled a far heavier load, be-

cause they move each item many times.

From mine to smelter, to mill, to part fac-

tory, to assembly plant, our goods move

from raw material to completion as engines

of war, making each move by rail in a steady

stream on which the flow of production is

utterly dependent. Once assembled, the war

machine goes to troops by rail, then moves

with troops from training camp to maneuver

area, back to training camp, and again to

port of embarkation. Then, on its arrival

abroad, the railroads resume the burden.

All the vast new factories, munitions de-

pots, and training camps, springing up in

sections where industry and population had

been small, have been built and supplied

with men and materials brought by rail.

Freight traffic, which formerly moved pre-

dominantly eastward through yards and ter- |

minals built to take it, now runs west in al-

most equal flow—to the great Pacific ports

of embarkation, to the plane factories of

California, to the shipyards of the North-

west. Why, for just one of Kaiser's Liberty

ships, it takes a trainload of steel, which

must arrive on time. And then the train re-

turns, carrying copper or timber which ordi-

narily would have moved via the Panama

Canal, now closed to merchant trade.

All this has gone on while trains rushed

oil to the East; while millions of travelers,

deprived of rubber, have rushed to the rail

roads; and while troop movements have

reached a fantastic level. Where soldiers of

1918 moved perhaps three times by rail while

training, today’s troops move six to eight

times, on trips averaging 800 miles, often

spanning the continent. Transportation has |

been used prodigally, because the railroads

could provide it. And the remarkable thing

is that they provide it with almost no new

equipment. Sidings have been lengthened to

hold longer trains, intricate electric traffic

controls have been installed to accommodate

far more trains on a single track, yards have

been built. But in general the rolling stock

is little more than it was in quiet 1939. The

new streamlined trains have kept running at

full speed. The new 4,500-horsepower Diesels

have hauled away unceasingly, dragging

great loads across the western mountains.

But a great part of the increase has been

through the intensive use of equipment

which had seemed almost ready for discard.

Intensive management has done the trick.

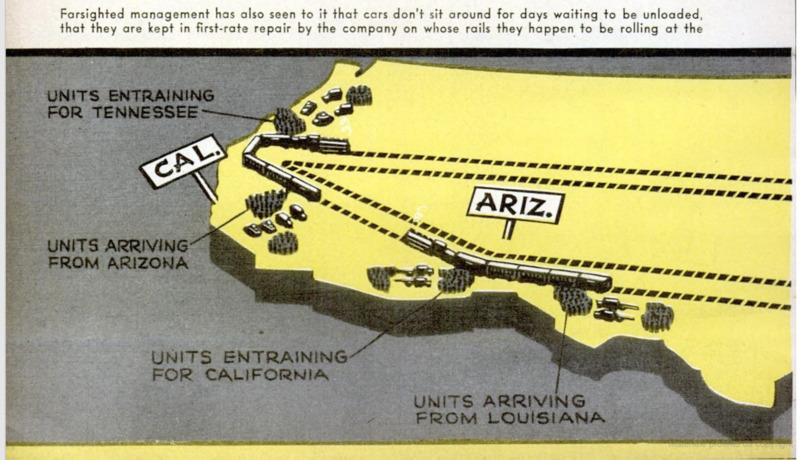

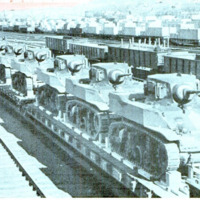

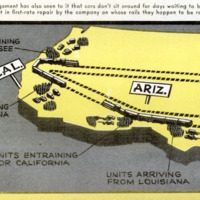

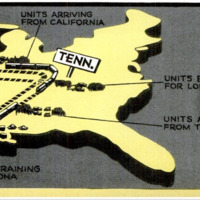

For instance, it takes about 1,300 cars— |

passenger and freight—to move an armored

division. A few years ago such equipment

would have been immobilized for days or

weeks after making a special run. But last

spring, within a period of six weeks, one set

of equipment moved seven divisions, on

trips of several thousand miles.

First the trains, carrying troops with their

tanks, moved one division from Fort Knox

down to Camp Polk, in Louisiana. As each

train unloaded, it picked up a unit from an-

other division, bound for the Arizona desert

area. From then on to California, back to

the Tennessee maneuver area, again to Loui-

siana and the desert, and back to California

and Tennessee. That series of movements,

which could be accomplished only by care-

ful advance planning and scheduling, is one

of the prize accomplishments of the military

transportation section of the Association of

American Railroads, a civilian unit quar-

tered in the Pentagon Building outside of

Washington, where it functions virtually as

a part of the Army, moving more than 2,500

special trains a month.

At one time during the First World Wax

there were tied up In eastern terminals and

yards more than 200,000 freight cars, far

more than could be unloaded, while other

parts of the country were suffering from

car shortages. The job had been botched, so

the Government took over the railroads and

botched it some more. But all the fault was

not on the railroads or the Government.

Much of it was due to faulty planning by

shippers.

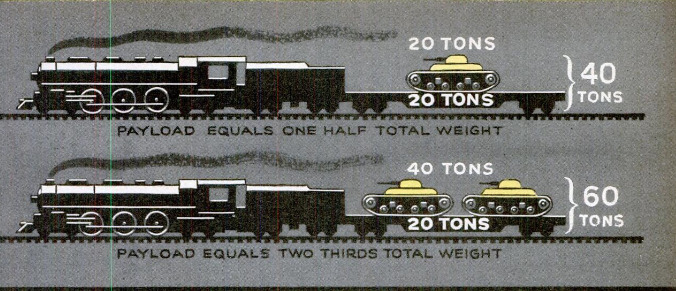

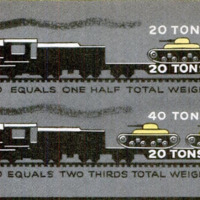

The railroads and the Government both

had more foresight this time. Locomotive

power has been conserved by running longer

trains, by keeping engines on the road for

longer runs, and by loading cars more heavi-

ly. When a 20-ton car is loaded with 20 tons

of freight, only half of what the engine pulls

is payload. But load that car to capacity of

40 tons or more, and the locomotive is pull-

ing twice as much freight while its total load

is increased only by one half.

All purely military _transportation—of

troops, Army freight, and goods for Lend-

Lease—is under direction of the Army

Transportation Corps, set up after Pearl

Harbor as a part of the Services of Supply,

under command of Major General Charles P.

Gross, In this country, the actual work is

done by the roads themselves, co-operating

under the leadership of their Association of

American Railroads.

But once overseas, the Army takes con-

trol and its own railroad troops man the

trains, in co-operation with our allies. Long

before the war our railroad military units

were set up as part of the Army reserves,

entire skeleton outfits drawn from individual

railways, with operating battalions modeled

ater the organization division, and shop and

maintenance battalions.On three rail systems across the north of

Africa today American railroad men in uni-

form are working with a motley collection of

French civilians, Algerians, and British sol-

diers, working with everything from the

oldest of narrow-gauge engines to the new-

est of American cars and locomotives, un-

crated and assembled on the spot. And as

the African and Italian campaigns show,

they have been getting results. Farther east,

other American railway troops work in

partnership with Persians, running the

trans-Iranian Railway, from the Persian

Gulf cross the mountains to Russia, moving

the great flood of Lend-Lease supplies.

Over there they have new cars and new

locomotives, thousands of them where they

are needed most, and there will be plenty

more when the troops move in on Europe.

They are moving the stuff that will win the

war; and whether or not they talk the same

language, whether they are in uniform or

not, they all understand each other on that.

For they are all railroad men.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Hickman Powell (writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1943-11

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

73-76

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

Popular Science Monthly, vol. 143, n. 5, 1943

Popular Science Monthly, vol. 143, n. 5, 1943