-

Titolo

-

Fighting on a thousand fronts is "Ghost Light" our new weapon in the dark

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Fighting on a thousand fronts is "Ghost Light" our new weapon in the dark

-

extracted text

-

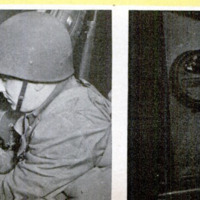

A LEADER of a night scouting party |

consults his map. As he is near the

enemy lines, it would be suicide to strike

a match or use a flashlight. No need.

Printed in luminous ink, lines of the map |

shine dimly but clearly in the dark. |

The party moves on. Lest his men be-

come separated from him, the leader wears |

a faintly glowing button on his back. |

Similarly, to the rear, ghostly processions |

of blacked-out tanks and troop-loaded trucks |

are advancing in follow-the-leader style,

each guided by a spot of luminous paint

on the one ahead. |

Now the scouts have completed their

mission. To mark directions for the secret

troop movement, they have daubed roads

and trees with splotches of ordinary-looking

paint. When a soldier turns the invisible

beam of a special black-light flashlamp upon |

one of the painted direction markers, it lights |

up as plainly as a traffic signal. |

Through 30 centuries, from the time when

ancient Egyptians used light-emitting min-

erals to create a mysterious glow around

tempie altars, the phenomenon called lumi-

nescence remained no more than a showy

novelty. It turned up in the theater, where

seemingly unoccupied shoes tapped brightly

across an unlit stage, and where costumes

and scenery gave striking luminous effects.

It came down to earth, and into everyday

life, in fluorescent lamps for homes, offices,

factories, and outdoor displays. From this

beginning, its practical uses on war and

home fronts are multiplying constantly.

According to a recent order, all ships of

more than 3,000 tons using New York Har-

bor must have doors, stairways, control

valves, steam pipes, and other important

points marked with luminous paint. Thus, in

case a torpedo puts the regular lighting

system out of commission, sailors can still

make repairs or find their way to lifeboats.

Direction markers pointing to air-raid shel-

ters, and the shelters themselves, may use

“firefly” illumination in total blackouts. Set-

ting an example for motorists in air-raid

precautions; New York's Mayor La Guar-

dia uses a car with phosphorescent fenders

and bumpers. Many London streets and

sidewalks now are outlined with luminous

strips or curb markers, which we may pos-

sibly adopt in coastal areas.

Fluorescent powders can be used for test-

ing the soundness of a gas mask. They are

spread on the outside of the mask, the

wearer takes several breaths, and the in-

terior then is examined under black light

for telltale glow.

Cases of arson and other forms of sabo-

tage committed with pilfered explosives

have been cleared up by injecting traces

of fluorescent dye into the waxed-paper

wrappings of sticks of dynamite, and the

gums and glues that go into bombs. It is

impossible to handle them without getting

traces of the dye into the pores of the skin.

Suspects, rounded up and questioned in a

routine way, are then suddenly exposed to

black light. The dramatic evidence of glow-

ing hands seldom fails to obtain confessions.

Senders of false fire alarms, and passers of

counterfeit money, have been trapped by

somewhat similar means.

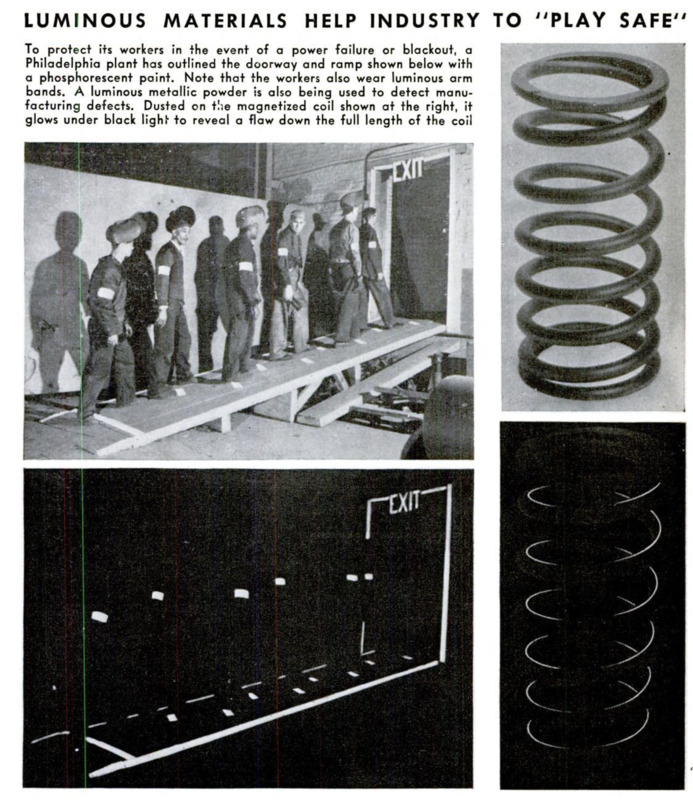

In a standard industrial

test for flaws in castings

and stampings, the piece

is magnetized and dusted

with metallic powder,

which outlines any cracks

or internal defects. A

recent improvement on

this scheme makes the

powder luminous under

black light, giving a more

conspicuous and sensi-

tive test. The method

will also test a surface

for freedom from oil.

Medical workers find

a new tool in fluorescent

stains. Cancerous and

other cells treated with

these dyes and examined

under a microscope with

black-light illumination

reveal characteristics

that can be observed in

no other way.

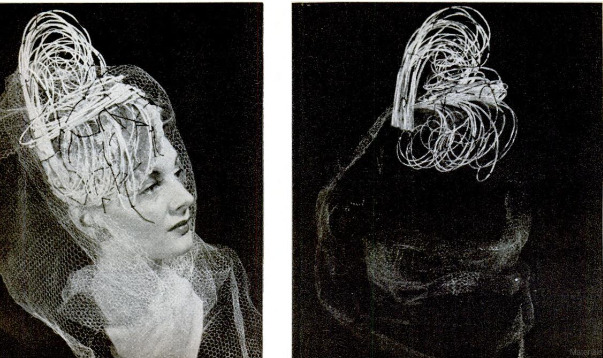

For “blackout parties,”

originated in raid-dark-

ened London, luminous

clothes and furniture pro-

vide the only light in the

house — except in such

games as “blackout golf,”

played with a self-glow-

ing club, ball, and indoor

putting green. Fashion

fads include luminous

dresses, capes, hats,

stockings, hairdress, and jewelry.

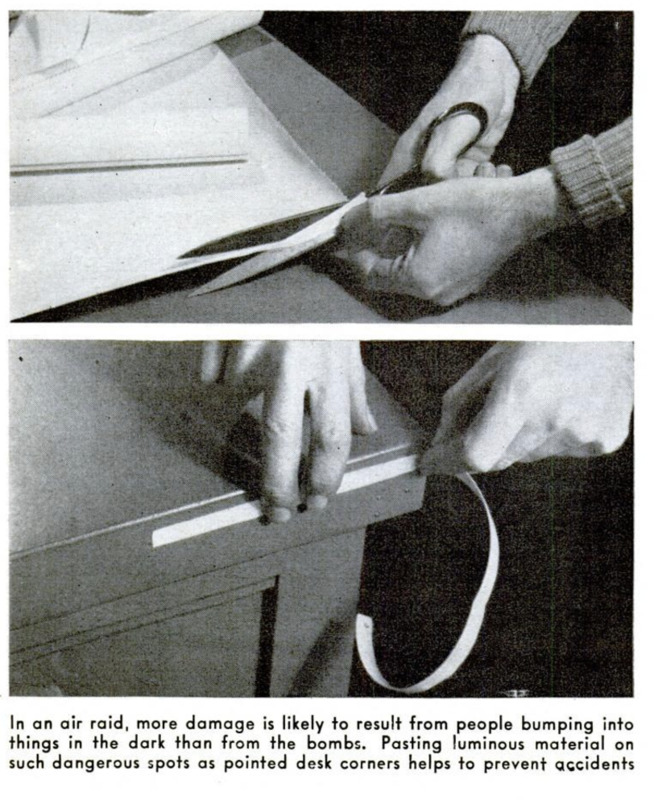

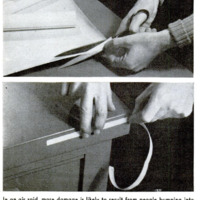

More practical domestic uses of modern

luminous paint will reduce our yearly toll

of 30,000 fatal home accidents. Danger spots

such as stair treads and electric fans glow

all night when outlined with long-wearing

phosphorescent preparations. Applied to

street numbers, doorknobs, keyholes, and

light switches, they serve a home owner's

convenience without using electricity.

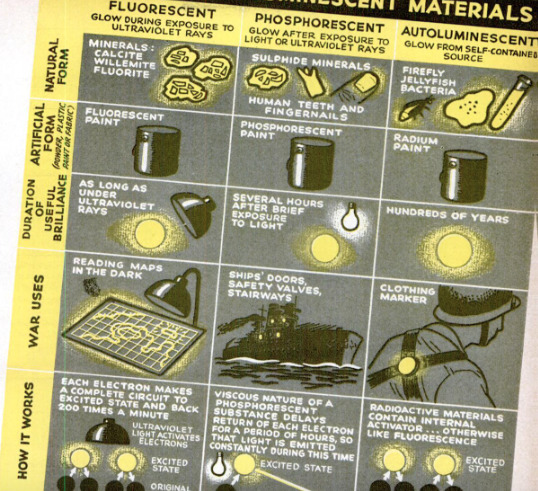

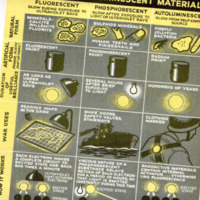

Scientists classify luminescent materials

into three or more distinct kinds, according

to their behavior, which in turn decides

which is best suited for a given use.

Fluorescent substances glow just so long

as they are exposed to ultraviolet rays—

popularly known as black light—and no

longer. This property has suggested the

war use of fluorescent buoys to guide friend-

ly ships through channels in mine fields,

when illuminated momentarily by a black-

light searchlight. Of the many known

fluorescent minerals, some are ores of stra-

tegic war metals. Important deposits of

tungsten ore have been located by night

prospecting with black-light equipment.

Phosphorescent materials soak up illumi-

nation from the sun or from artificial light.

Then they proceed to reradiate it for several

hours, without exterior stimulation. Lumi-

nous paint made from such substances pro-

vides all-around service and is unaffected

by power failure. One of its former disad-

vantages—that it could not be extinguished

at will—is now reported to have been over-

come by Gilbert T. Schmidling, a pioneer

American research worker in the field. By

illuminating it with strong red light, he says,

the phosphorescence can be “put out.” Sub-

sequent illumination with sunlight turns it

on again.

Self-illumination, or autoluminescence, oc-

curs spontaneously from a variety of chemi-

cal and physical actions. The firefly, nature's

prize example, owes its glow to a slow form

of chemical oxidation, which has been dupli-

cated in the laboratory. Crystals of saccha-

rin emit light when crushed or rubbed

together. The luminous paint employed on

watch dials provides permanent light by

bombarding a metallic sulphide with rays

from radium.

-

Autore secondario

-

Jean Ackermann (writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1943-11

-

pagine

-

98-101

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)