-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Why our aerial gunners are Outshooting the Axis

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Why our aerial gunners are Outshooting the Axis

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

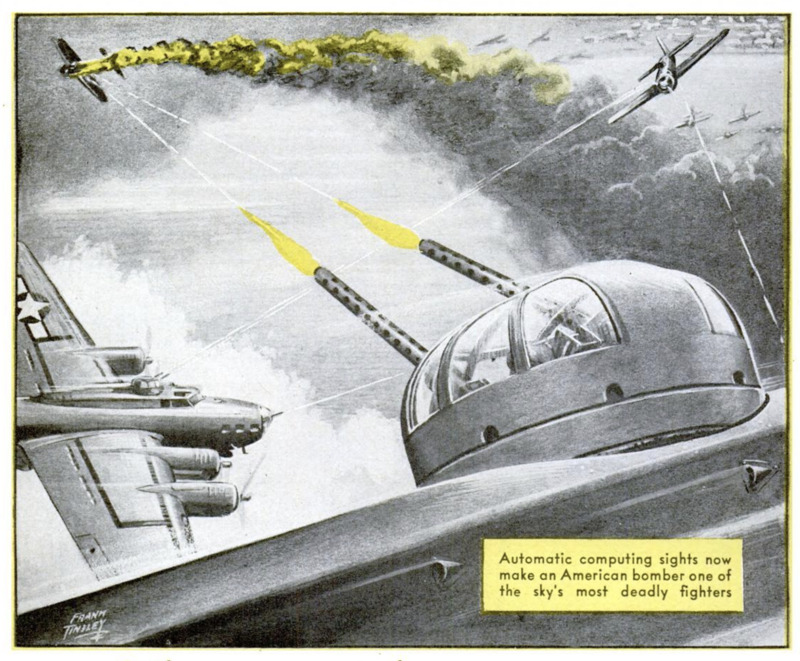

AMERICA'’S big bombers, which roared to

fame as tough ships that could “lay

eggs in a basket” from 20,000 feet and take

terrific punishment, are even more famous

now as killers of the sky. On one bombing

mission, not long ago, a flight of them

knocked out 74 Nazi fighters. Good to be-

gin with, they are now superbly lethal.

How come? The answer is gunnery—

gunnery that is more than weapons, more

than power turrets, more than competent

gunners. It is all these, plus an automatic

computing gunsight that makes supermen

of the bombers’ gun crews. This automatic

sight has given our big ships a fire-power

“reach” of more than 1,000 yards, or twice |

the effective range of Axis aerial guns.

Until recently this automatic sight was a

secret weapon. Its details are still secret, but |

the veil has been lifted enough to show what |

it can do and, in general, how it does it. Basi- |

cally, it is a compact machine that automat- |

ically calculates speed, drift, windage, tra-

Jjectory, and range, and compensates for all |

these factors as it aims the guns where the

bullets will do the most damage to an eneray

plane. It does all this with a minimum of hu-

man effort, and reduces human error to a |

minor factor by eliminating virtually all

guesswork. And, lastly, it is so simple to

operate that three weeks’ training with it

can make an expert gunner out of a novice.

Any duck hunter or trapshooter has a

rough idea of the primary problems of an

aerial gunner. First of all, to hit a moving

target he must “lead” it, that is, shoot far

enough ahead of it to allow for its speed.

Then he must take into account the range

of his gun, the effect of the wind, and the

characteristics of the shell he is shooting.

The duck hunter's target, however, sel-

dom flies more than 60 miles an hour. The

aerial gunner’s target travels more than six

times as fast. And while the duck hunter

shoots from a stationary position, the aerial

gunner is in a bucking, twisting ship travel-

ing at least 200 miles an hour. The duck

hunter uses a shell whose hundreds of tiny

pellets are deadly over a three-foot circle

at 50 yards. The aerial gunner's weapon

fires only one bullet at a time. To approxi-

mate the aerial gunner's task, the duck

hunter would have to do his wing shooting

with an automatic rifle while sitting in the

rumble seat of a -ar going down a country

road at : ) miles an hour. Accurate shoot-

ing from a big bomber with manually op- |

erated weapons ond ordinary sights is phe- |

nomenal. Man simply is not physically

equipped to <7 it.

Of his equipment, his eyes are probably |

nearest to the necessary perfection. When

a bomber is flying at 200 miles an hour and

an oncoming pursuit ship is moving at 400

miles an hour, the combined speed of ap- |

proach is 300 yards a second, which is not

very far from the speed of sound. Yet a |

gunners eye can follow a pursult ship travel- |

ing at that terrific speed. In a wink of the |

eye, however, the target will have moved

about 25 yards. And we know from optical

research that persistence of vision makes

the eye incapable of registering an abrupt

change nating less than 1/32 of a second. |

The eye Is fallible to degree not vet fully

determined; but, on the whole, it is good

enough for the aerial gunner's Job.

A man's physical reflexes ure less de- |

pendable. But because of thelr importance,

the Air Forces insist on high standards. Im:

pulses from the eye or ear must be obeyed

by the muscles without perceptible delay.

Tests of thousands of automobile drivers

have shown an average reaction Ing of 44 |

second. Yet in half that time an aerial gun-

ner's target may move as much as 66 yards.

A trigger finger even a tenth of a second

late In obeying the eye's order to fire would

Put the burst of fire completely off the tar.

get, even if no other factors were involved.

Mental processes are another factor. The |

best mathematical mind Isn't fast enough

to solve, at a given instant, a problem deal-

ing With alr speeds of hundreds of yards a

second, particularly when such compiex mat. |

ters as windage, drift, trajectory, and range

are also involved. That Is why the guns in

a fighter plane are in fixed mounts: they can

be aimed by pointing the plane itself, and no

complicated calculations are necessary.

Add to the gunner's problems the fact |

that high altitudes slow up both physical re-

flexes and mental processes, and then the

situation become really complicated. OXy-

gen helps to compensate for the altitude,

but low temperatures—it gets down as far

aa 45 below zero F. at 25,000 to 30,000 feet

also tend to retard the reflexes.

The automatic computing sight was de- |

veloped to minimize all these human factors. |

It is a mechanical Einstein that literally

computes half a dozen complex and con- |

stantly changing problems, and delivers the |

correct answer at any desired instant. Al-

though the gunner sights at the target it-

self, the computer aims the guns at the

point where the target will be when they

go into action.

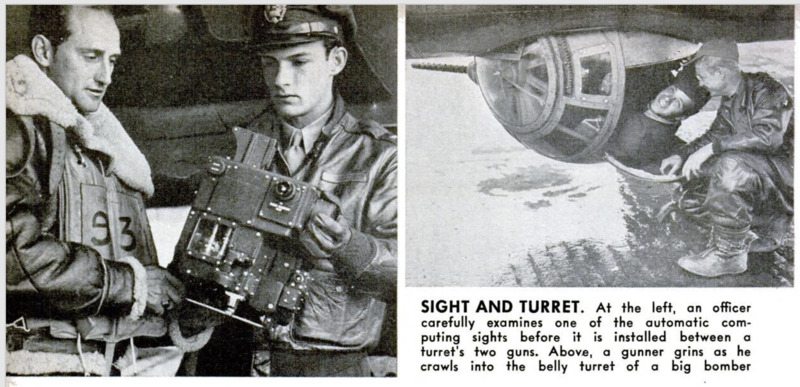

Typical of several models is the sight de-

veloped by the Sperry Gyroscope Company

for use with a hydraulically driven turret. |

Looking like an ordinary small black box, it

is mounted between the turrets two guns.

At one end of the box are knobs similar to

the tuning knobs on a radio. On its top is

a reflecting glass—the scanning sight— |

with two parallel lines of light Which can

be spread apart or drawn together by man- |

ual control or a foot pedal. These light lines |

are the governors of the range finder.

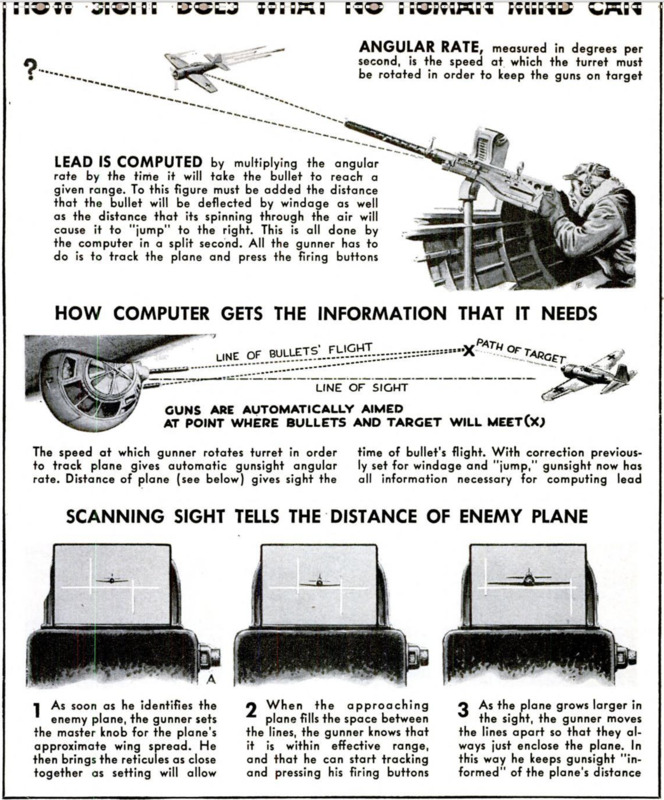

Before the take-off, the computer is set

for the type of ammunition used and wind- |

age jump, or deflection to the right caused

by the spin of the bullet. After the take-off,

another adjustment is made to compensate

for the plane's speed. A power switch takes |

the manual labor out of the gunner's job by

making the turret swing automatically in

accordance with the “orders” from the sight.

The gunner has a pair of handle bars |

with firing buttons at his finger tips. When |

he spots an enemy plane approaching, he |

identifies it by type and sets a master knob

on the sight at the plane's approximate wing |

spread. A Messerschmitt, for example, with

a wing spread of about 33 feet, will call for |

a setting at that figure. Swinging the tur-

ret until the oncoming target is framed in |

his reflecting glass, the gunner brings the |

light lines to their minimum spread, which

is governed by the master knob setting

when he identified the enemy plane. Since

the over-all dimensions of a fighter are ap-

proximately the same from any angle, he

has only to Keep the plane between the

light lines, and as soon as the target fills

the space between the lines it is within

range. At that point, the gunner can be-

gin effective fire, and can continue it as

long as the light lines enclose the approach-

ing plane’s extremities.

Everything has been compensated for au-

tomatically—range, speed, windage, deflec-

tion, and angular rate. All he has to do is

track the plane, and press the firing buttons.

All American medium and heavy bombers

are now equipped with automatic computing

sights and power turrets of one type or an-

other. This accounts for the lopsided scores

when bombers go out and run into fighter

opposition. Neither the Japs nor the Ger-

mans have power turrets or computing

sights, and, considering the development

necessary to bring them to perfection and

the precision work needed to manufacture

them, it is unlikely that the Axis will pro-

duce such a sight unless the war drags on

considerably longer than now seems likely.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Hal Borland (writer)

-

Frank Tinsley (illustrator)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1943-11

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

112-115

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

Popular Science Monthly, vol. 143, n. 5, 1943

Popular Science Monthly, vol. 143, n. 5, 1943