-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

U. S. Modern Infantry Vehicles

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

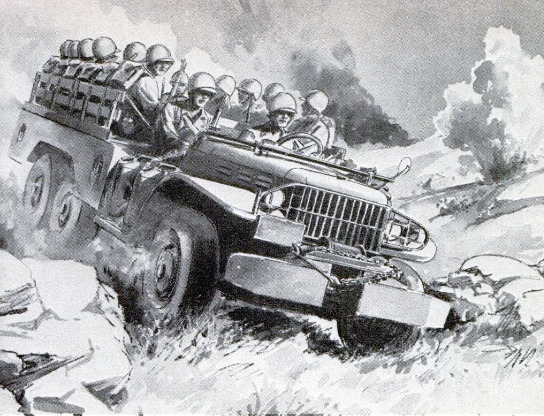

Modern Infantry Rides to Battle on Wheels...and Fights on Its Feet

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

MOTORIZED infantry, a new weapon

in the American arsenal, has now

met the finai test of major battle,

and many military observers believe that

these high-wheeling foot soldiers will deal

the decisive and finishing blows in the great-

est war of world history.

Fast infantry is a relatively new concept

in war. From the dim days of Cyrus the

Great to the first World War, the fate of bat-

tles and nations was decided, in the main,

by the shock of troops who marched and

maneuvered at the classical pace of three

miles an hour.

‘The gasoline engine has changed all that.

A modern motorized infantry division can

move 10 miles per hour over poor roads, 15

over secondary roads, and 20 or 25 on good

highways. In terms of battle strategy, this

means that troops who used to move to the

battle front at 15 to 25 miles a day can now

approach action at 100 to 150 miles a day.

The whole pace of a military operation de-

velops about six times faster than in the past.

This speed-up has greatly increased the

advantage of the force that can seize and

hold the initiative. It has made this a truly

offensive war, as contrasted with the grind-

ing defensive struggle which the trench and

machine gun made of World War I.

Motorization also has put the element of

deception back into large-scale war by mak-

ing possible the rapid grouping of forces for

an attack at an enemy weak point. In World

War I, the opposing commanders had to de-

pend almost entirely on railroads, and it

took weeks to pile up the overpowering

quantity of supplies and troops needed to

mount an offensive.

Motorized infantry has not cut so spectac-

ular a figure in the war reports as its mech-

anized partner, the armored force, yet its

basic function is fully as important as that

of the tank formations. It nails down and

exploits the gains that the tanks batter out;

to use an analogy with football, the tank

first opens a hole in the enemy line, and

then the motorized division carries the ball.

‘There is a practical reason for this. The

armored division, preceded by infiltrating in-

fantry, is formidable in attack, but has rela-

tively little defensive strength or holding

power. It is never more vulnerable than at

the moment when its forward lunge has been

halted, its headlong momentum spent. That

is when the motorized division becomes es-

pecially valuable. Following the armored

striking force through the gap in the ene-

my’s formations, the fast infantry occupies

roads, crossings, bridges, towns, and other

strategic points. Then it fans out, rolling

back the flanks of the gap or curving back

to attack from the rear.

Moreover, if the initial break-through suc-

ceeds in disrupting the enemy resistance, the

main job of pursuit and destruction falls to

the motorized divisions. For this task they

have the right combination of great mobili-

ty plus great combat strength and fire pow-

er. They can hit hard to break up any re-

organized center of resistance, or, if the ene-

my develops a strong counterattack, they

can dig in and hold until the armored force

and other reinforcements are brought up to

strike again. This process, in which units

of an army take turns in striking and sup-

porting each other, is called “leapfrogging.”

‘The motorized division's function of pur-

suit after a break-through is of great im-

portance. Correspondents and commentators

who have studied the massive fighting in

Russia since 1041 are inclined to believe that

both the Nazis and the Russians missed

chances to win crushing and decisive vic-

tories in the first year by not having enough

motorized divisions to exploit initial success-

es. Both armies inflicted heavy defeats on

the enemy during their separate offensives;

neither side had enough fast infantry to

prevent the other from carrying out an or-

derly retreat.

‘There is nothing essentially mysterious or

startling in the organization of a motorized

infantry outfit. It is simply an infantry di-

vision permanently equipped with its own

motor transportation. The men ride their

vehicles to the zone of action, then dismount

and fight on foot as any other infantrymen

would.

The idea was tried out on a limited scale

during World War I. Wherever possible,

troops going up to the front were hauled by

truck; no soldier who rode very far in a

1916-model camion will ever forget the ex-

perience. But the number of trucks and

lorries that were available always was rela-

tively small. Major movements of troops

and equipment were pretty well confined

to the existing railway nets.

The modern motorized division, however,

rolls along in style, riding in some 3,000

vehicles of all types, ranging from the fast

scouting motorcycle to the heavy cargo

truck. Such a division will include about

12,000 men. It is slightly smaller than a

standard triangular infantry division, but

has greater fire power, mainly because it is

more lavishly equipped with automatic

weapons.

The U. S. motorized division has jeeps,

half-ton trucks, three-quarter-ton heavy-

weapons carriers, and 2 1/2-ton cargo trucks

and personnel carriers as its basic vehicles.

The omnipresent jeep is the all-purpose car,

serving as anything from reconnaissance car

to ammunition carrier. The handy three-

quarter-ton is now being standardized as the

Army's medium truck. It is squat and

strong in appearance, looking something like

a burly, overgrown jeep, and its low-slung

look has won it the nickname of “Toad"—a

term believed to have originated among the

men of the Sixth U. S. Motorized Division.

Aside from these basic cars the division

has many specialized vehicles, including ar-

mored scout cars, self-propelled artillery,

mobile repair shops, command cars, Medi-

cal and Signal Corps cars. The infantrymen

themselves ride the 2 1/2-tons, 20 of them toa

truck with their full field equipment on

board.

‘Enemy aircraft are extremely dangerous

to a moving truck column, of course, and a

sharp watch is kept. Every other truck in

the moving line carries a .50 caliber machine

gun on an antiaircraft mount.

In normal circumstances the cars are

required to keep a considerable interval

between them on the road, to lessen the

damage from a bomo or shell hit. As a re-

sult, a division may stretch from 20 to 30

miles along a road, and may take two hours

or more to pass. Such an outfit on the move

is an impressive demonstration of flexible,

controlled power rolling by. In dry weather

the cars kick up plenty of dust, and each

succeeding truck seems to loom up out of a

mist and lumber by, while the troops inside

stare out, some grinning and curious, some

intent and serious.

The complicated movezient of men and

machines goes on with remarkably little

confusion. Its marching orders havs been

drawn with railway-timetazle precisica, and

every unit must move by st the scheduled

time. The division has ite own military po-

lice company, primarily to handle traffic

problems at tough places along the road, and

road guides with painted signs and arrows

indicate the correct turns at intersections

to save even the little loss of time that might

be occasioned if the drivers had to slow

down slightly for directions.

‘Those traffic MP's are one example of spe-

cial troops attached to the division either

permanently or for temporary service. There

are many others. The American motorized

division is by no means a rigid organization,

and the Army has been consistently willing

to experiment and reshuffle the outfit to

build up its combat strength. The exact ta-

bles of organization of the new-type division

have not been published, but the general

character of such a division is well known.

Basic fighting units in a typical division

are three regiments of infantry and four

battalions of artillery. Three of these are

light artillery (105-millimeter gun-howitz-

ers) designed to support the three infantry

regiments. The fourth battalion usually

functions as divisional heavy artillery, and

is equipped with 155-mm. howitzers.

The motorized division is well equipped

for reconnaissance, being assigned a full

squadron of mechanized cavalry, as con-

trasted with the single troop that is allotted

to a regular triangular infantry division.

Other components of the motorized or-

ganization include one or two battalions of

engineers, medical and quartermaster bat-

talions, signal company, and ordnance units.

Special troops may be added for particular

‘missions—tanks or tank destroyers, for ex-

ample, or extra engineers trained specially

for river crossings or the neutralization of

mine fields.

The division, in any case, is not regarded

as a rigid, unalterable organization, and

does not try to fight that way. Its combat

operations rather are based on the principle

of the combat team. The entire trend of

modern war is toward the creation of these

teams—special task forces flexibly organized

and built up to whatever strength appears

to be needed for the specific mission in hand.

Combat teams can be of any size, from a

squad to an army. In normal divisional op-

erations, however, the commander (usually

a major general) would be likely to arrange

his force in three combat teams. Each of

these would be built around a regiment of

infantry and a battalion of light artillery.

Reconnaissance, engineers, tank units, and

other forces are added as they are needed.

The infantry regiment, incidentally, provides

an extra punch for the team with its own

cannon company, which functions as an in-

tegral part of the regiment. The main self-

propelled weapons ‘are the TS-mm. gun

mounted on & half-track vehicle and the

Dewer 105mm. on full-track chassis like

that of a medium tank. These 105, which

gave the Germans such a nasty surprise

hen they were first used in North Africa,

fot the nickname of “Priests” from the

British troops because of the pulpitiike ap-

pearance of their antiaircraft machine-gun

Turrets,

The infantry regiment's colonel is the

logical commander of a combat team of this

size, and in the course of a battle he may

often find it advisable to assign smaller

teams within his own force to carry out

particular tasks. To a large degree & mod-

ern battle, even on the greatest scale, con

sists of a vast complex of relatively small

actions by teams.

“An enemy outfit which tries to meet this

attack by the old technique of stringing out

along a wide front soon finds Itself being

chewed up and disrupted by the hard-hitting

teams, which pick their own points of at-

tack and always have great local superiority

at the places they strike.

‘When the division moves up for combat,

ts reconnaissance force normally leads the

‘way. However, as the mechanized cavalry-

men are likely to get out 50 miles or more

ahead, the division supplements them with

a close reconnaissance of its own, maialy

carried out by infantrymen with rifles and

‘machine guns in jeeps.

“The actual widih of the divisional front

varies widely according to the terrain, the

nature of the operation, and the size of the

enemy force. It can be as narrow as a few

hundred yards or as wide as several miles,

especially if two. forces are trying

to outtank each other f open country. &

‘motorized division hates to depend on a sin-

gle road; two roads is the minimum it likes

to move on, and the more alternative routes

it finds available, the better use it can make

of its mobility in maneuver.

Military men have sharply divergent opin-

fons an one of the most important factors in

the tactical employment of motorized in-

fantry—the point at which the men should

be dismounted for action. One school of

thought bolds that this should be done when

the vehicles come within range of enemy

light artillery, while another believes that

the dismounting is not necessary until the

trucks come within range of effective small-

arms fire.

The first range suggested would be 10,000

yards, which seems pretty far back. And

the second would be 2.000 yards, which may

or may not be too close. On the whole, the

German example in the first two years of

the war seems to indicate that the speed and

‘mobility gained justify the risk in bringing

the vehicles extremely close to the action.

The Nazis even worked out a technique un-

der which special infantry shock troops—

pancerjaegers—were attached to the ar-

mored forces. Their task was to mop up

scattered enemy resistance in the gap made

Dy the tank attack, so that the motorized in-

fantry could be rushed through and dis-

‘mounted in position to strike the enemy's

‘main body from the rear.

The normal pattern of a modern attack

‘most often proceeds with reconnaissance in

the lead, then the armored striking force,

then the motorized divisions to exploit the

attack, and finally the regular infantry to

occupy the territory and anchor the new

position against a counterattack. (In some

situations, however, the entire attack may

be led by special shock infantry and en-

gineers trained to knock out fortifications

and dig up mine fields)

‘When an engagement is being prepared,

the division must find the best possible con.

cealment for its (Continued on page 218)

vehicles from hostile aircraft. This is no

small problem, since there are some 3,000

cars and trucks to be hidden.

As a result, in a zone of poor concealment,

the division's bivouac area may cover an

area of six by eight miles, while in a heavily

forested region it can be much smaller. In

open plains or desert country, little or no

concealment is possible, and about all that

can be done is to disperse the vehicles widely

to limit the damage possible from one bomb

hit or shell burst.

Most carefully concealed of all, when the

division is in bivouac, is the command post,

the guiding brain of the entire organization.

‘This post may be fairly elaborate in a rela-

tively stable area; if the division is moving

fast it probably will be in a single vehicle.

In either case, it is the nerve center of the

widespread net of communications—tele-

phones, teletype, radio circuits, messengers,

and signaling—which controls and co-or-

dinates the entire outfit.

Laymen sometimes ask why, i* motoriza-

tion confers such advantages, all infantry

isn't on wheels. The answer is that while

all modern divisions have vehicles for spe-

cial purposes, the complete motorization of

an entire army would be ruinously expensive

and would create impossible problems of

traffic and supply at the front. There is a

point at which even the best vehicles will

begin to get in each other's way. And, even

the motorized division must normally de-

pend on railway transportation from the

rear bases.

‘Take the matter of fuel alone. The figures

on gasoline consumption of American divi-

sions are not published, but some idea can

be gleaned from material recently released

by British sources which have made a study

of German fuel consumption. This took an

average of all German vehicles—light,

heavy, and armored—in the proportions in

which they are used in combat operations.

American organizations probably use about

the same amounts; our gasoline is of better

quality than much of the German synthetic

product, but, on the other hand, our cars

run to more horsepower than theirs and we

use the jeep far more than the motorcycle.

The survey indicated that a German or-

ganization the size of our motorized division

would require 100,000 gallons of gas to

move 100 miles on the road. That is about

400 tons of gasoline, and it would take some

100 tank trucks to haul it. Truly, in 1943

an army marches on its fuel tank as well

as on its stomach.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

John H. Walker (writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1943-12

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

62-66, 218

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

Popular Science Monthly, vol. 143, n. 6, 1943

Popular Science Monthly, vol. 143, n. 6, 1943