-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

U. S. rifles and pistols in five wars

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

U. S. rifles and pistols in five wars

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

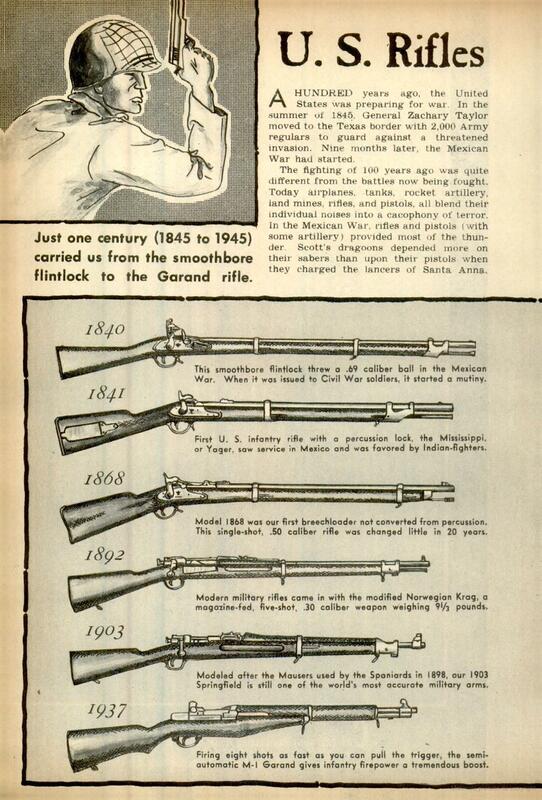

A HUNDRED years ago, the United

States was preparing for war. In the

summer of 1845. General Zachary Taylor

moved to the Texas border with 2,000 Army

regulars to guard against a threatened

invasion. Nine months later, the Mexican

War had started.

The fighting of 100 years ago was quite

different from the battles now being fought.

Today airplanes. tanks, rocket artillery,

land mines, rifies, and pistols, all blend their

individual noises into a cacophony of terror.

In the Mexican War, rifles and pistols (with

some artillery) provided most of the thun-

der. Scott's dragoons depended more on

their sabers than upon their pistols when

they charged the lancers of Santa Anna.

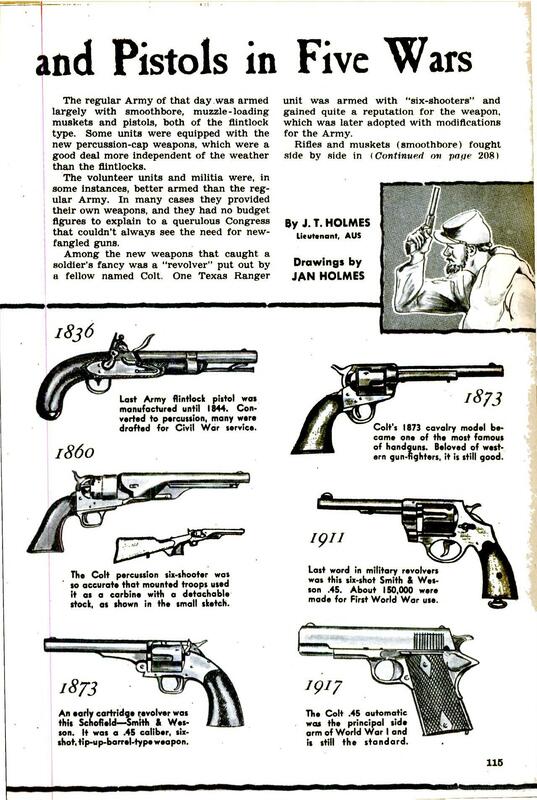

The regular Army of that day was armed

largely with smoothbore, muzzle-loading

muskets and pistols, both of the flintlock

type. Some units were equipped with the

new percussion-cap weapons, which were a

good deal more independent of the weather

than the flintlocks.

The volunteer units and militia were, in

some instances, better armed than the reg-

ular Army. In many cases they provided

their own weapons, and they had no budget

figures to explain to a querulous Congress

that couldn't always see the need for new-

fangled guns.

Among the new weapons that caught a

soldier's fancy was a ‘‘revolver” put out by

a fellow named Colt. One Texas Ranger

unit was armed with “six-shooters” and

gained quite a reputation for the weapon,

which was later adopted with modifications

for the Army.

Rifles and muskets (smoothbore) fought

side by side in

this war. The older smoothbores were prac-

tically useless beyond 50 to 100 yards, and

most battles were fought at close range

with a good deal of bayonet and sword

work involved. The Mexican Army, cor-

ruptly administered, was more poorly

equipped than the American, and practi-

cally every type of shoddy foreign gun could

be found on the battlefields.

The Mexican War brought home the fact

that improvements were necessary in mili-

tary firearms, and inventors were encour-

aged to go to work. The Civil War found

the nation still trying to standardize its

military firearms, however. Probably no

conflict in history has brought together so

many antiquated and modern—for the time

— weapons. Flintlocks, muskets, rifles, re-

peating rifles, single-shot carbines, repeat-

ing carbines; flintlock pistols, “six-shoot-

ers” percussion single-shots, “pepper

boxes,” and derringers faced each other at

Bull Run and Cold Harbor, Gettysburg and

Antietam.

The shortage of manufacturing facilities

on both sides brought about the importation

of foreign arms from Belgium, Germany,

England, and any other nation that had mili-

tary junk to sell. In the end, the industrial

facilities of the North tipped the scales, and

the South was defeated by Yankees firing

guns said to be “loaded on Sunday and fired

all week.”

‘The Civil War spelled the doom of the

muzzle-loader. After the battle of Gettys-

burg in 1863, some 20,000 guns were col-

lected from the battlefield. Examination

at an arsenal showed that anywhere from

two to 23 charges were rammed down one

on top of the other in a very heavy per-

centage of the weapons! It was quite ap-

parent that breechloaders had to be de-

veloped, or half of the soldiers might as

well be armed with sticks. Standardiza-

tion also was decided upon, as investiga-

tion showed some 69 types of rifles being

used, most of them calling for special types

of ammunition.

For economy, many of the old muzzle-

loaders were converted to breechloaders in

the years following the Civil War. The

same was true of pistols, although their

development was ahead of that of the shoul-

der weapons.

In 1873 a new-model, single-shot breech-

loader, which fired a cartridge .45 inch in

diameter, was adopted. This weapon went

through a series of modifications and was

used until about 1892. During all these

years, the Army was experimenting and

testing all types of military rifles and pis-

tols that were being used elsewhere in the

world.

Around the 1890's a board of Army of-

ficers decided to adopt the Norwegian Krag

rifle as the standard infantry arm for the

U.S. This was the first of the .30 calibers,

or “pencil” bullets, as they were called.

The rifle was modified in 1896 and used in

the Spanish-American War.

In this war, the regular Army had the

advantage over the militia and volunteers,

who were largely armed with the older-

model Springfields, which fired the old black-

powder cartridge. Loud laments were heard

every time a round was fired. A cloud of

white smoke gave away the firer’s position

to the Spaniards, who cracked down with

their superior Mausers and smokeless pow-

der.

Following the successful conclusion of

this war, it was decided that we needed a.

rifle incorporating the advantages of the

Mauser with American refinements. The

result was the now famous Model 1903

Springfield, which was the standard infan-

try rifle until the beginning of the pres-

ent war.

A Filipino rebellion next occupied the

Army, and it was found that the .38 caliber

pistols in use did not have sufficient shock-

ing power to stop the fanatical enemy. The

result was the .45 caliber Colt automatic

pistol developed in 1905, which was stand-

ardized with improvements in 1911. This

gun was used through the First World War,

and it is the standard side arm today, al-

though some revolvers are still in use at

the present time.

The First World War did not bring about

any startling developments in rifles or pis-

tols, perhaps because the need for large

quantities of arms enforced standardization.

Because we could not manufacture the

Springfield rifle fast enough to equip our

fast-growing Army, a large proportion of

American infantrymen carried the British

Lee-Enfield. Various types of automatic

weapons were brought out.

America was ready for this war with the

finest semi-automatic rifle in the world. It

was the eight-shot, rapid-fire, accurate Gar-

and. It was a rude shock to a Jap soldier

to wait until five rounds had been fired by

an American soldier and then charge with

the bayonet, only to find that he still faced

a loaded gun. Both the Germans and Jap-

anese have attempted to copy this efficient

weapon, but so far neither has been not-

ably successful.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

J. L. Holmes (article writer)

-

Jan Holmes (drawings)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1945-05

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

114-115,208

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 146, n. 5, 1945

Popular Science Monthly, v. 146, n. 5, 1945