-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

They learn about jets from her

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

They learn about jets from her

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

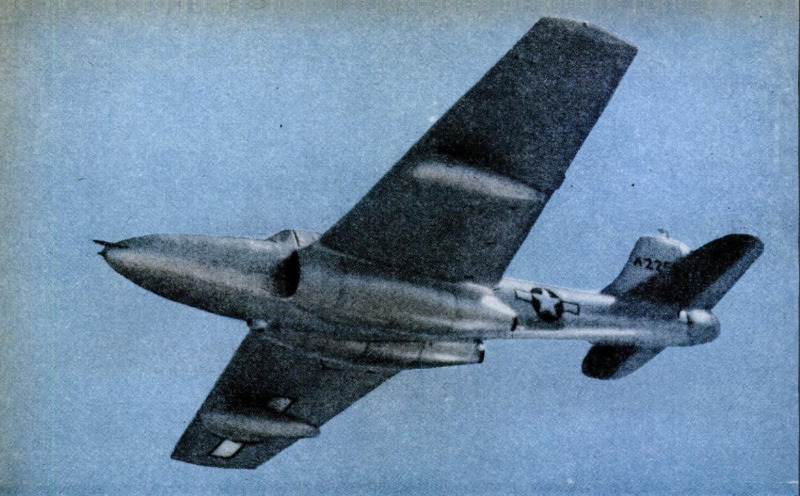

AMERICAN jet-fighter pilots, who soon

will be taking the new P-80 Shooting

Star into action, learned their stuff in the

P-50 Airacomet, the Army's twin-engine

jet fighter-trainer. For months tests have

been run, tactics developed, and pilots

checked out on the P-59. It has been the

primary test ship for our present jet pro-

gram, and lessons are still being learned

from it, both on the ground and in the air.

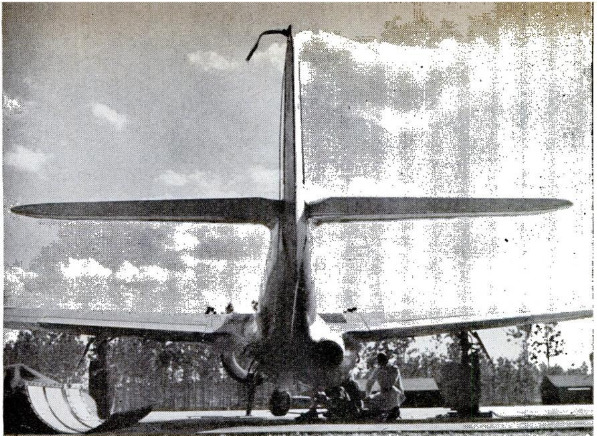

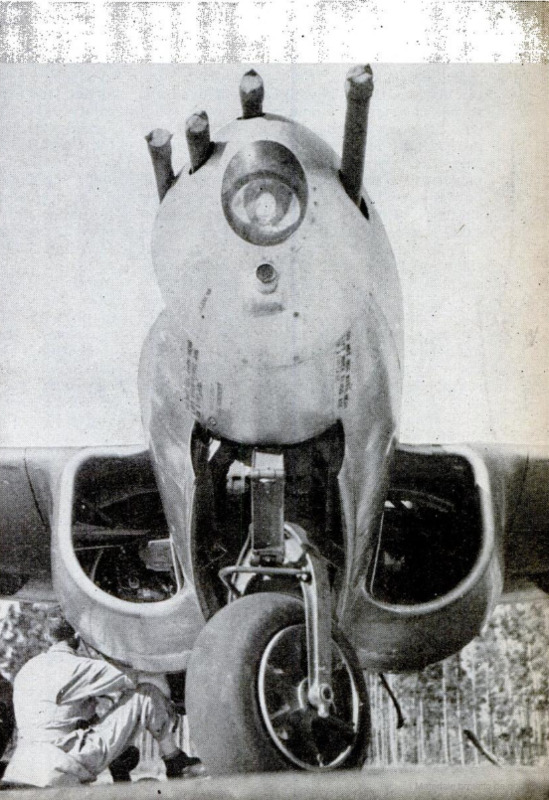

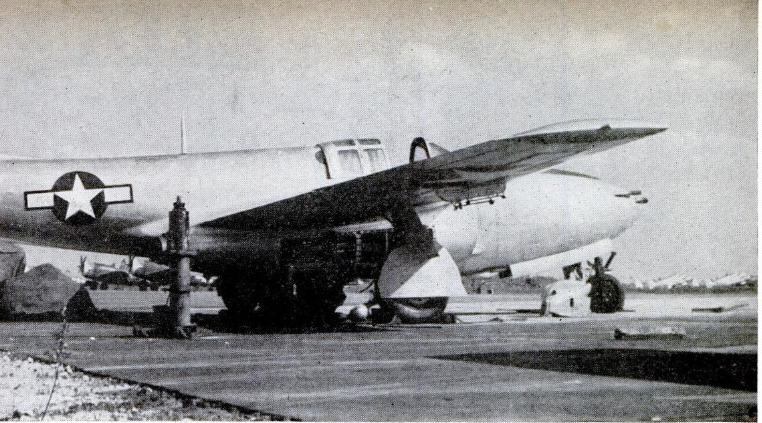

On the ground, it's not a particularly im-

pressive plane. Unusual, yes, for it looks a

bit like a Kingeobras fuselage with mid

wings and no prop and unusually stubby

landing gear. Seen from the front, it seems

to goggle at you from two vacant, close-set

eyes, the intake ports for the engine nacelles,

which are faired into the fuselage just un-

der the wings. In side view, it has a sway-

back appearance, for its tail rides high to

clear the blast from the engines.

Then the starters whirr and the engines

spit flame, a few seconds of orange fire that

roars away into a shimmer of blue heat.

Dust whips up 75 or 100 feet back of the

plane. Brakes are released and the ship

lumbers away, turns awkwardly down the

runway. She quickly gathers speed, lifts,

and is airborne. Up she goes, at an aston-

ishing angle of climb. Suddenly you realize

that there goes the jet ship, an airplane

without a propeller, without a piston, with-

out anything like the engine you always

considered necessary to take a plane into

the air and Keep it there. This ship has

“squirted” itself into the air with a couple

of outsize oil stoves and a pair of whistling

fans. Tn fact, its most noticeable noise is

the tinny whistle you associate with the

sudden acceleration of a big electric fan.

And when it really gets going you don't

hear even that sound until the ship is past

you. Then you hear that strange rumbling

Toar peculiar to the jet ships, the growl of

violently disturbed air that sounds like a

freight train between two high hills.

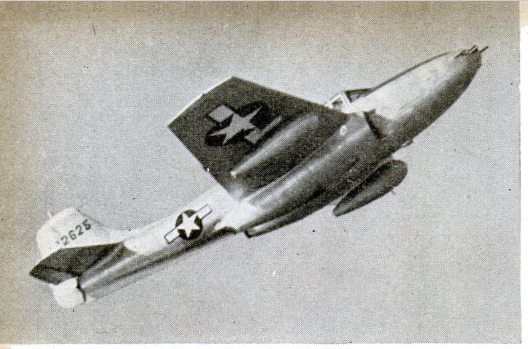

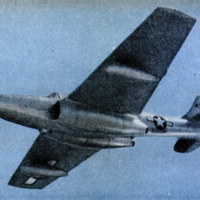

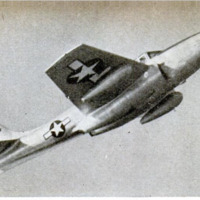

The ship climbs swiftly, levels off, gathers

speed. The pilot puts it through maneuvers,

Just to show you its paces.

No doubt about it, the

Airacomet handles with

remarkable ease at con-

ventional speeds. Then he

goes on up, where the air

starts to thin out, and he

begins to open her up. She

looks like a gnat up there,

a silvery. gnat in a great

hurry. She streaks for the

far horizon, and you real-

ize that the talk about jet-

plane speed is more than

talk.

Then she comes back, in

a wide sweep over the

field, losing altitude very

slowly. One sweep, and

another, and still she is

gliding in; and then she

comes leisurely down

toward the runway, kill-

ing speed, dropping n al-

most like a glider. Down,

down—still with a lot of

lift, although she seems to

be coming in no faster

than a Cub plane. Then

she is in. She sort of

hunches down, sets her

wheels on the ground,

quivers a little, and rolls

down the runway to a stop.

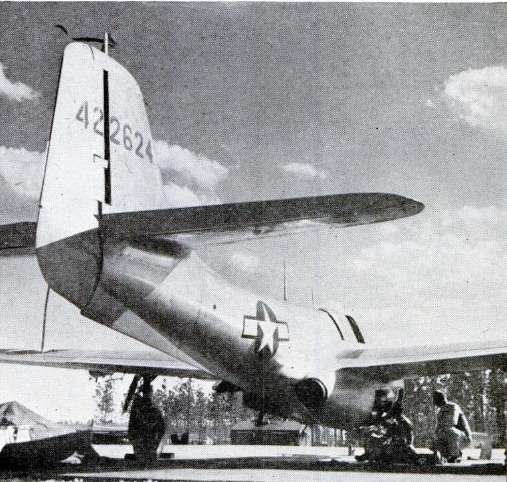

Technically speaking,

the P-59 is a mid-wing

‘monoplane with a span about three feet less

than that of a P-38. As it comes off the as-

sembly line, the P-59 weighs about five tons.

It has a tricycle landing gear with wing

wheels exceptionally far apart. Landing

gear is fully retractable. It is a single-place

ship with conventional-type controls. Horse-

power of its twin jet engines Is undisclosed,

but the somewhat larger engine in the

single-jet P-80 is said to develop around

4,000 horsepower. Top speed also is undis-

closed, but both German and British jet

ships are known to be able to top 500 miles

an hour. Officially, the P-59 has “over 400

mph” Its speed and efficiency increase

with altitude, and its ceiling is officially

listed as over 40,000 feet. Pilot's compart-

ment is pressurized, but the pilot uses oxy-

gen even at the usual levels for the simple

reason that the oxygen in the cabin's air is

s00n exhausted.

Mechanics fall in love with the ship. The

engines are unbelievably simple, having only

two moving parts, the impeller or com-

pressor, and the turbine which drives it,

both attached to the same shaft. All told,

the jet engine has only about one tenth as

many parts as the conventional reciprocat-

ing engine. A whole engine can be removed

from the P-50 in just a bit over half an

hour, and the mechs say they can remove

and replace both engines in a short day.

Further, they don't need a mech stand to

work on these engines. Actually, they use a

garage mechanic's “creeper” for a good

deal of the work, because the engines are

50 low the mechanics work flat on their

backs a good deal of the time,

The jet engines will operate on almost

any inflammable hydrocarbon, but kerosene

has been used and found most satisactory

in most of the test and tactical work done

at the Air Forces Tactical Center in Florida.

Pilots and engineers say, however, that they

can run the ship on anything from hair

tonic to brandy.

Pilots have many kind words for this

ship. “It handles as easy as a glider,” one

pilot says—adding, “at average speeds.”

Actually, at the speed of a conventional

plane it ‘seems to handle with exceptional

ease, and the boys say it takes them back to

“stick-and-rudder days.” Complete lack of

torque contributes to its easy performance.

Other factors are low wing loading and lack

of propeller drag. It has such a flat glide

that some of the pilots will tell you it coasts

three times as far as the ordinary pursuit

ship. This is evident when you watch the

ship land; it has to stall around and kill

speed for an unusual time before it settles

down. Most pilots overshoot their mark the

first few times they try to land it. This is

also caused, in part, by the short landing-

gear struts. The jet plane sits much closer

to the ground than propeller-type ships.

The P-59 has unusually good stall char

acteristics. Pilots say it gives ample warn-

ing, shuddering, then falling off straight

ahead without yawing into a spin. “When

you want to spin,” says ome pilot, ‘she

handles like a baby buggy. I've turned out

of a five-turn spin in three quarters of a

turn. On accelerated turns, though, you've

got to watch your step. When you're hitting

400 mph. you reach four G's (four times

gravity's pull) in a hell of a hurry. Just a

few seconds of that and you black out, un-

less you've got a G suit to protect you.”

There is virtually no engine vibration in

a jet plane. About the only moise is the

swish and roar of air on its wings, with the

background rumble of the jet engines’ pow-

er exhaust. Lack of vibration greatly les-

sens pilot fatigue and improves pilot ef-

ficiency and reaction. Again, the pilots liken

the feeling to glider flying. At conventional

speeds, that is, above 400 miles an hour, it's

something else again. This lack of vibration

raised an unusual instrument problem in

the P-50. The pilots

had to put “rattlers”

on the instruments to

make sure they were

working; they didn’t

trust them without the

usual vibration rattle.

The P-59 is a twin-

jet job, but she can fly

and land on one jet.

“And she has plenty

of speed on one,” the

pilots assure you. Be-

cause the two jets are

snuggled close to the

fuselage instead of

out on the wings, the

failure or cutout of

one jet does not great-

ly alter the flying

characteristics of the

ship.

Those who see the jet ship for the first

time often wonder about the suction of the

engine intakes and the blast from the jet

nozzles. There is a strong suction at the |

intake, and in the air it might conceivably

gobble up a few birds. To prevent this, pro-

tective screens are used. The nozzle blast

is dangerous—as dangerous as the arc of a

whirling propeller. Anyone walking into |

that blast 20 feet

from the ship probably would feel as

though he had walked into the path of a

flame thrower. Fifty feet away he might be

knocked from his feet, but he wouldn't get

badly burned.

Principal problem of today’s jet planes

has been fuel consumption—lack of range.

Jet engines have been far from economical

on take-off or at low speed and altitude.

Only at high altitude and speed have they

been as economical as conventional airplane

engines. The Germans also have had to

face this problem, which has limited opera-

tional range. But our engineers seem to be

well on their way to a solution; official an-

nouncement of the P-80 says that it “op-

erates over any of the ranges at which

conventional pursuit ships of today are

called upon to perform.”

Among the pilots who checked out on the

P-50 were boys who, flying our conventional

fighters, had faced German jet planes over

Europe. How does the P-59 compare with

the German jet jobs? “I couldn't say,” one

such pilot replies with a smile. “I never

flew one of the German jobs. And they

never stuck around long enough for us to

study them.” In combat, the German fet

planes usually operate at extreme speeds,

‘making perhaps one or two passes at a con-

ventional fighter and then getting away

from there in a hurry. At such speeds, our

pilots generally agree, the German jets are

slow in maneuver, and a conventional Amer-

ican fighter plane can side-step them unless

the pilot is caught completely by surprise.

The German jets traveling 500 m.p.h. or

better seem to need about five miles to turn

around. Our conventional fighters can turn

in about a mile at around 400 m.p.h.

‘The pilots do indicate, however, that the

P-50 at the speed of a conventional fighter

—that is, around 400 m.p.h.—probably can

outmaneuver the best of the German or Jap

conventional fighters. In addition, it has at

least the extreme speed of the German jet

Jobs, with consequent loss of maneuver-

ability.

The future of the fet plane is anybody's

guess. You hear all kinds of predictions.

Lawrence D. Bell, president of the Bell

Aircraft Corp, which built the Airacomet,

says: “Within five years no military fighter

planes will be built which do not incorporate

the jet-propulsion principle. There is no

doubt that jet-powered planes will make

all present types obsolete in years to

come.” That opinion is not universal, even

among those who have worked a good deal

with the jets. But there is no doubt that

the jet plane is already opening a new

horizon in flying.

Right now one can sum up the advan-

tages of the jet plane in this way:

It has more speed and a higher ceiling

than the conventionally powered ship.

It has less weight per horsepower at alti-

tudes of equal operating efficiency.

It has considerably fewer working parts,

which means less danger of breakdown; it

also means simplified maintenance.

A practical pilot, with plenty of hours

over enemy territory and a respectable

number of enemy kills to his credit, sums

it up this way:

“The fet is fast as all hell. It can out-

climb anything else I've ever seen. It can

outmaneuver most of them at their own

speeds. It would be a honey for strafing, or

for attacking bombers, or probably for dog-

fighting, though today you usually make a

couple Of swift passes and get him or get

the hell out. It's a thoroughly sweet ship.

But T'd like to know what happens to her

when she takes a piece of flak or a few

50's through those windmill furnaces of

hers. Maybe I'm jittery, but I know how

the ships I've been flying over there—the

propeller ships—act when that happens. 1

know how much they'll take and still bring

me back. When I know as much about the

Jet jobs, then I can speak with authority.

Meanwhile, she's one sweet ship to fly.

Ain't had so much fun since I was a kid in

high school.”

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Hal Borland (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1945-06

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

82-85,212, 216

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 146, n. 6, 1945

Popular Science Monthly, v. 146, n. 6, 1945