-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

From stuntman paratrooper How armies hit the silk

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

From stuntman paratrooper How armies hit the silk

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

THE airborne forces that parachuted to

earth beyond the watchers on the Rhine

this spring mushroomed out of an idea that

is older than Uncle Sam. The parachute

vas invented before the airplane, but, until

after World War I, parachuting was mainly

a showman’s stunt, on a par with sword

swallowing.

The French flyer who saw a German pop

out of a burning plane and float gently into

a storm of bullets in no man’s land in 1917

was flabbergasted. His generation of air-

men had felt that anyone who was seriously

interested in ways of deserting his ship was

a sissy.

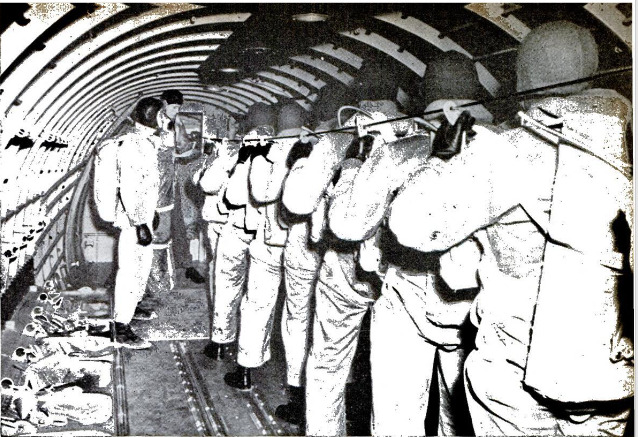

But the parachute now ranks with the

lifeboat, the first-aid kit, and the chariot as

‘one of mankind's super-duper ideas. It is no

longer a mere fire escape from the heavens

for pilots; it can be used now to deliver al-

most anything that can be taken up in a

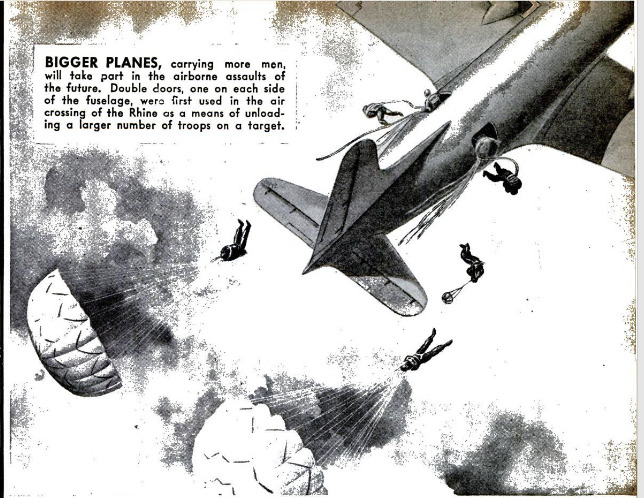

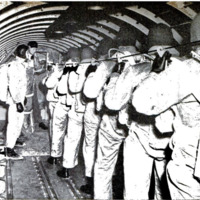

plane. Electrically driven conveyor belts

dump cargo bundles into thin air from some

planes, and doors were cut in both sides of

the C-46 Commandos that flew over the

Rhine, so that two columns of paratroops

could march out simultaneously and descend

in double file.

Such surprising assaults from the sky

stem from scientific research that was

started during the last war—and continued

after the Armistice.

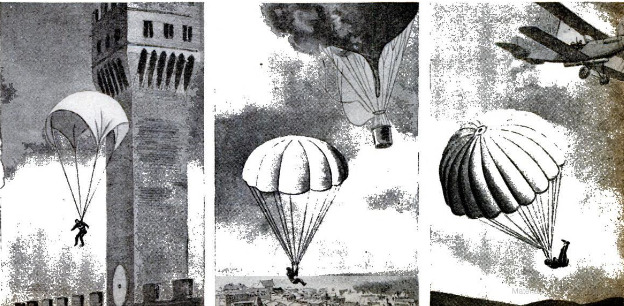

Nearly five centuries ago Leonardo da

Vinci drew a picture showing how a man

with “a tent of calked linen” could “let him-

self fall from any great height without

danger to himself,” and between 1780 and

1800, when men began to go up in balloons,

some of them came down this way.

The first parachutes had rigid frames and

were far from perfect mechanically. Pro- |

fessional daredevils devised nonrigid para-

chutes, beneath which they hung on trapeze

bars. The speed of airplanes increased the

hazards. Capt. Albert Berry made the first

successful drop from an airplane in 1012

with a ‘chute that had been packed in a

metal cylinder under the planes fuselage.

But the First World War was over before

any country had developed a ‘chute that

could be guaranteed to open on leaving an

airplane.

Interest waned considerably when peace

came, but Major E. L. Hoffman and a num.

ber of other Americans persisted. Leslie

Irvin saw Houdini produce a huge flag from |

a tiny container, and thought of making a |

parachute out of silk and squeezing it into a |

small pack. Other noteworthy features of

the parachute that he produced were a sim-

ple rip cord and a pilot parachute to pull |

out the main canopy.

“PLANE FAILED, PARACHUTE

WORKED,” Jimmy Doolittle happily wired

the Irving Air Chute Company 14 years ago,

after a thrilling escape from a damaged

plane in the National Air Races. That four- |

Word message was a climax to years of re

search, including more than 50,000 tests with

dummies. And the same four words now |

summarize more adventures than there's

paper enough to print.

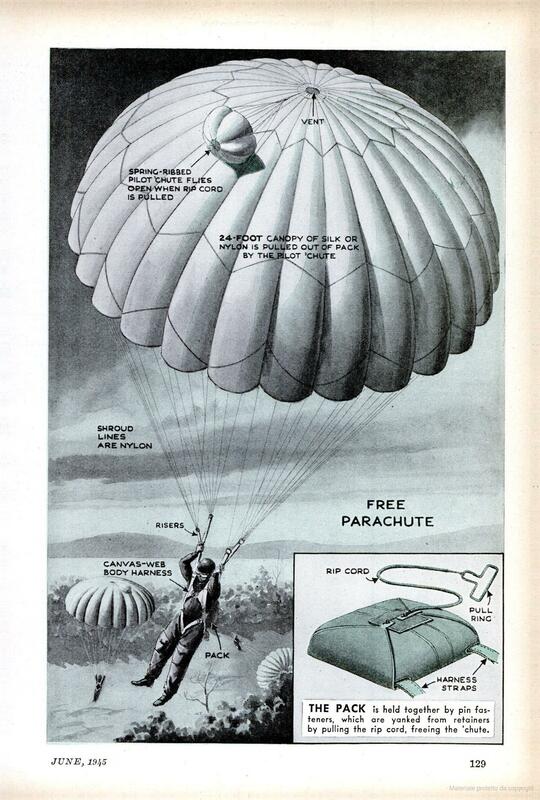

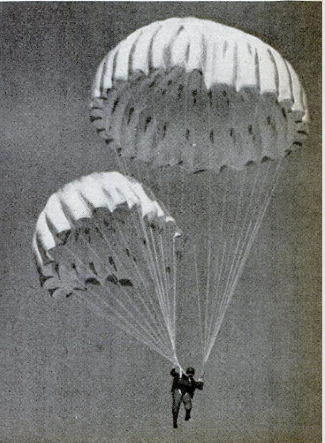

The parachutes used nowadays are thor-

oughly reliable mechanisms. Both the “free” |

‘chutes, used in emergency descents, and the

“automatic” type, worn by paratroopers

and pulled open by a canvas-web “static

line” attached to the plane, are trustworthy

conveyances. Unusual conditions and human

errors still result in mishaps, but young

pilots now are told emphatically:

“Don’t take chances. Hit the silk if some-

thing goes wrong. We can build ten of these

planes in the time it takes to train you.”

This advice has been stressed because,

even after airmen were ordered to wear

parachutes, flyers persisted in an attitude

comparable to that of sailors who refuse to

learn how to swim. The importance of the

know-how is better realized now. Well-

trained paratroops have been injured in

leaps only about one sixteenth as often as

flight crews. Such statistics prompted the

AAF Office of Flying Safety to wage an ex-

tensive educational campaign among air

personnel in 1943, and brightly colored post-

ers now hang in air stations to remind com-

bat flyers of the correct way to descend be-

neath a blossoming awning.

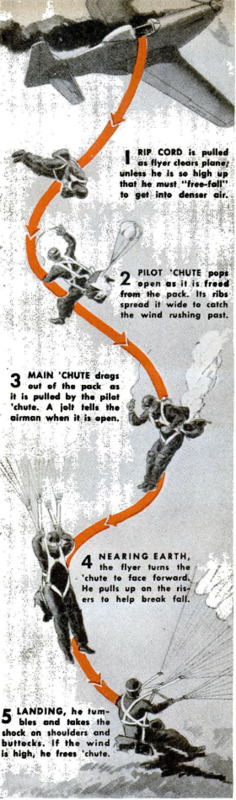

‘To get out of a stricken, 400-mile-an-hour

fighter with an enclosed cockpit, or a big,

complex, misbehaving bomber, a man still

may need luck as well as a cool head and

technical skill. Most combat planes now are

fitted with automatic door or canopy re-

leases, some of which are spring-assisted

and actually fly off. Bombers have escape

hatches forward and aft, and the gaping

hole of the bomb bay may be used in a

pinch. But it pays 1945 candidates for mem-

bership in the Caterpillar Club to keep in

mind “three A's”:

Altitude: “Am 1 high enough to have

time for the "chute to open? Paratroops are

dropped from low but carefully predeter-

mined altitudes. If T'm very high, I must

connect the oxygen bottle on my leg, or

make a free fall until I reach ‘breathing’

air.”

Attitude: “The best attitude for a bail-

out is upside down. Can I roll the plane over

and fall out? If the ship is diving, I must

brace my feet lest I be thrown forward

when I unbuckle the safety belt. If the ship

is spinning, T'd better go out the correct

side—toward the inside of the spin, So the

tail will be swinging away from me.”

Air Speed: “Will I be going 400 miles an

hour when I leave the plane? That's too

fast. ‘Body speed’ in a normal free fall be-

fore a ‘chute opens is only about 125 miles an

hour. Can T fall free until T have slowed

down nearer to that speed?”

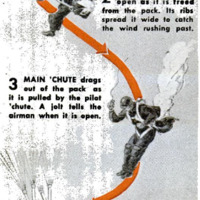

As he falls away, the wise parachutist

keeps his legs together to avoid tangling the

harness and risers when he pulls the rip

cord. A jolt tells him when the ‘chute opens;

if he finds himself swinging too much, he

steadies the magic carpet above him by

pulling at the shrouds on the high side of

each swing. He then looks downwind for

a likely landing spot, and grasps the

shrouds to swing the ‘chute so that he is

facing the way the parachute is drifting.

If trees or other obstacles loom in his path,

he sideslips by pulling down on the shrouds

on one side.

As he hits the ground, he pulls up strongly

on the risers. He lands with his feet to-

gether and his body and knees slightly bent.

He doesn't try to stay on his feet, but tum-

bles, taking the shock of the roll on his

shoulders and buttocks. A man coming down

straight, without oscillating, in a standard

24-foot parachute hits the ground about as

hard as though he had jumped off an eight-

foot wall.

If the wind is high, the well-trained para-

chutist unbuckles the hagness leg straps be-

fore touching the ground, unsnaps the chest

buckle the instant he lands, to free himsel

from the dragging ‘chute. He takes pains,

however, to save his ‘chute if possible, by

spilling the wind out and collapsing it as

s00n as he has landed—because a parachute

is often as nice to have on the ground as in

the air.

Stranded airmen have used their para-

chutes to make tents, clothing, bandages,

slingshots, fish lines, snowshoes, and scores

of other handy items. One sergeant, to at-

tract the attention of planes searching for

him, touched a match to the rubberized

horsehair cushion of his ‘chute, and the black

column of smoke that it sent up led to his

rescue.

‘Pure silk parachutes are considered best,

especially in northern climes, and some are

still being made in this country from Japa-

nese silk bought before the war. But many

parachutes now ‘are made of nylon, or ace-

tate fabrics such as celanese, milanese, or

rayon. Cargo parachutes are made of mer-

cerized cotton and rayon, and those for

flares and fragmentation bombs of specially

processed paper. Experts at the Parachute

Laboratory of the Materiel Command at

Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio, have developed

dozens of different kinds and sizes of ‘chutes.

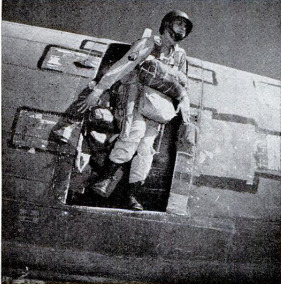

Both seat-pack and chest-pack parachutes

are available that can be attached to a

man's harness by snap buckles in a Jiffy.

Bomber crews and Navy airmen wear the

harnesses that go with these packs. They

can walk around the whirling propellers on

a crowded carrier deck, or move about in-

side a plane, without being encumbered with

packs, yet can hook them on quickly when

they need them.

Food and other necessities are stored in

some modern military parachutes. The

AAF B-4 Basic Emergency Kit is zippered

into a canvas case which is attached to the

‘chute harness in place of the back or seat

pad normally worn for comfort. This outfit

includes a_feather-stuffed poncho-quilt, a

folded machete, and a first-aid package as

well as a small supply of emergency rations.

The Navy has a similar kit that may be

substituted for the harness cushion, and

also a pararaft for carrier pilots. The in-

flatable raft is made of rubberized nylon

and stowed in a small roll on top of the

parachute pack. The raft is only large

enough for one man, but has a protective

cover and folded paddles.

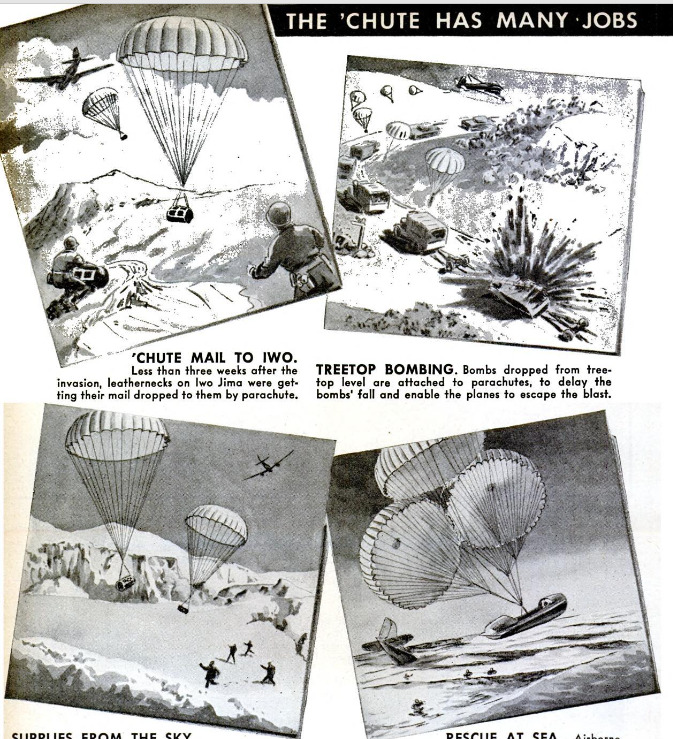

Rescue planes can spill more food, medi-

cines, and supplies on men downed on land

or sea. A Tropic Rescue Kit contains items

helpful to men lost in jungles or deserts,

and a Marine Rescue Kit has a canister full

of supplies for castaways.

Our Army learned a lot about packaging

and parachuting provisions from the U. S.

Forestry Service, whose asbestos-clad

“smoke jumpers” were being supplied by

parachute in fire fighting before the war,

Orange ‘chutes are used in the arctic, and

an orange flag pops up from some of the

containers used, to help men find the sup-

plies dropped for them. Other colors are

used in the tropics and, to facilitate the re-

covery of parachuted cargoes from trees, a

weighted line dangles from each bundle.

This line is about 75 feet long and brightly

colored, with a four-pound steel ball on one

end to carry it through foliage.

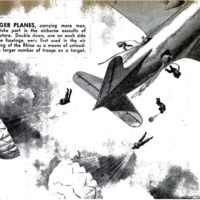

The paratroops of World War II have

given the most spectacular demonstrations

of Leonardo da Vinci's theory, but they are

still lightweights compared with other mili-

tary forces. Brig. Gen. Wiliam D. Old,

Commanding General of the I Troop Car.

rier Command, recently predicted “aerial de-

livery of standard ground-force divisions.”

“The armies of the future,” he warns,

“will not be as concerned with the frontiers

of enemy nations as with vital spots within

the nation itself. Thus, entire air-trans-

rorted armies may be landed in the heart

of the enemy's homeland and wage their

war from within—supplied, equipped, and

reinforced entirely by air.”

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

James L. H. Peck (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1945-06

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

128-135

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 146, n. 6, 1945

Popular Science Monthly, v. 146, n. 6, 1945

content.jfif

content.jfif Screenshot 2023-01-18 150117.png

Screenshot 2023-01-18 150117.png Screenshot 2023-01-18 150131.png

Screenshot 2023-01-18 150131.png Screenshot 2023-01-18 150142.png

Screenshot 2023-01-18 150142.png Screenshot 2023-01-18 150152.png

Screenshot 2023-01-18 150152.png Screenshot 2023-01-18 150205.png

Screenshot 2023-01-18 150205.png Screenshot 2023-01-18 150217.png

Screenshot 2023-01-18 150217.png Screenshot 2023-01-18 150228.png

Screenshot 2023-01-18 150228.png Screenshot 2023-01-18 150243.png

Screenshot 2023-01-18 150243.png Screenshot 2023-01-18 150255.png

Screenshot 2023-01-18 150255.png