-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

A dime is its landing field: jeep with wings

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

A dime is its landing field: jeep with wings

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

ABOVE the treeless volcanic isles at

Japan's back door, a new kind of war

has been fought with a weapon more than

40 years old. The unarmed airplane, intro-

duced at the start of World War I, returned

to service to help drive the Japs into their

inner citadel.

In the fighting that marked the start of

the Kaiser's war, the flimsy aircraft of the

period were used solely for reconnaissance.

In the mobile, seaborne fighting of the

Mikadc's war, the role of the plane that

drops no bombs and shoots no bullets be-

came that of an airborne scout car, ambu-

lance, motorcycle, and artillery observa-

tion post.

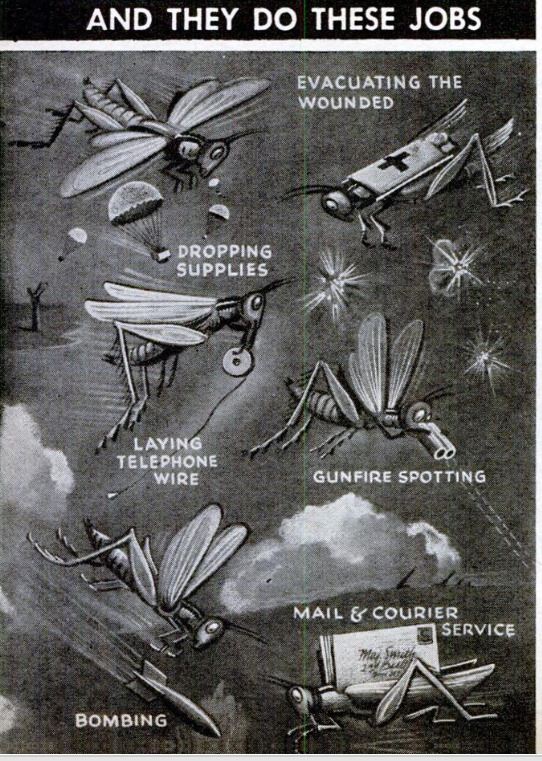

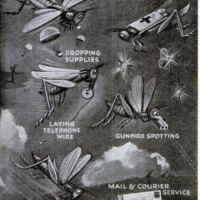

Of all the weapons that have been given

wings for fighting in a third dimension, the

“grasshopper” plane, often fitted with an

engine of less power than that of a small

automobile, is the most versatile. Grass-

hoppers have been used for almost every-

thing that requires transportation, even in-

cluding the laying of telephone wire to ad-

vanced observation posts over mountains.

Because they are slow and fly at treetop

level, and therefore make poor targets for

either ground gunners or enemy fighter

pilots, they are ideal vehicles for carrying

messages, directing highway traffic, and

dropping supplies to units cut off by the

swift ebb and flow of battle.

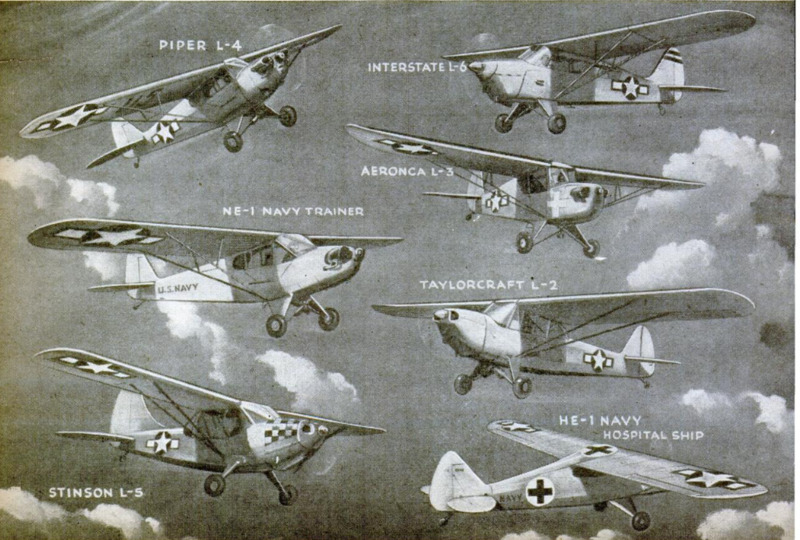

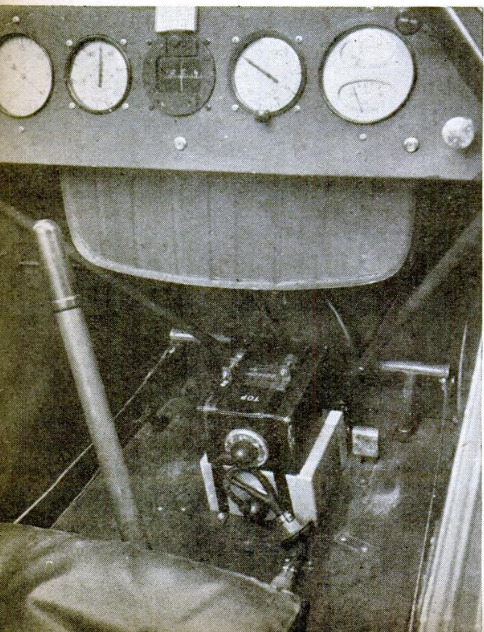

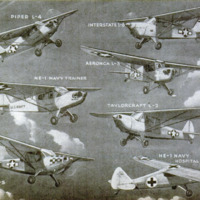

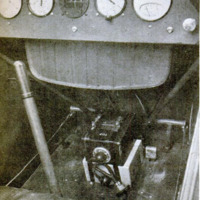

The grasshoppers are the same thing as

the small private planes that used to dot

the grassy, postage-stamp airports through-

out the United States before the war. They

have changed only their garb. Some of

them have a little more horsepower. They

carry two-way radio. A limited number,

flying for the Army, the Navy, and the

Marine Corps, are equipped with stretchers

for ambulance work.

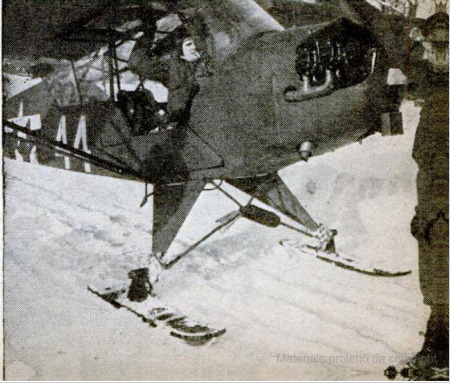

They require no regular landing fields.

The first of them on Guam—and they were

the first American planes to land there, as

well as on Iwo Jima—sat down on a short

strip of ground bucked flat by bulldozers.

They can put their wheels on the ground

and stop in less distance than the span of a

Superfortress wing. A favorite trick of the

grasshopper pilot facing an emergency is

to land in a treetop. It damages the plane,

but it's usually safe enough for the pilot.

With more affection than derision, the

grasshopper has been called a flying egg

beater, aeropeep, coffee grinder, and Maytag

Messerschmitt. It might well be called an

airjeep—aerial partner of the quarter-ton.

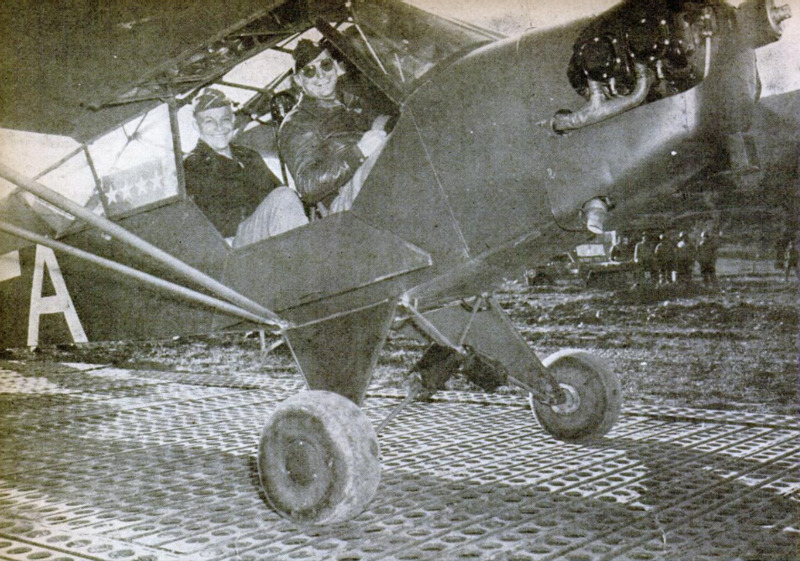

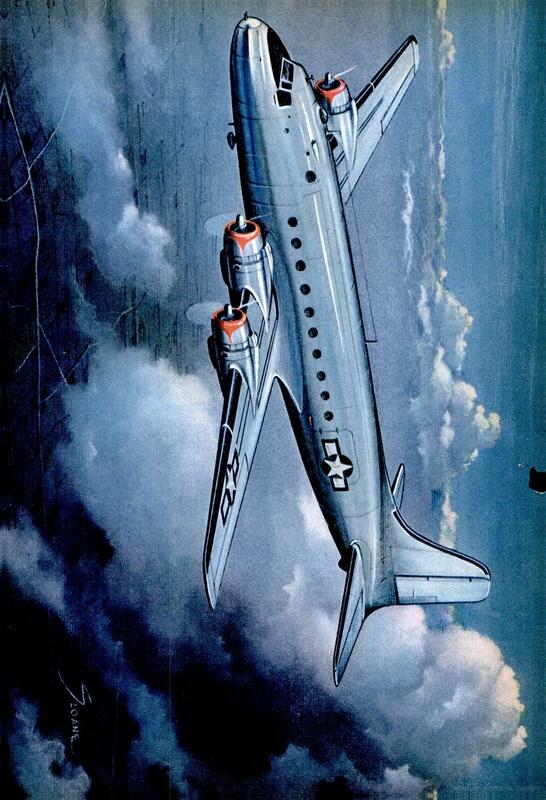

Airjeeps are at their best in artillery-

spotting work. Flying at 25 to 100 feet

above the ground, the pilot and his observer

—they carry a crew of only two—can see

everything on the ground.

During the invasion of Peleliu Island, in

the Palau group, airjeeps were flown off

carriers to direct Marine artillery fire. They

hovered over the Jap positions and radioed

ranges to the guns. During the shelling they

retired to an altitude of 1,000 feet to avoid

concussion. Then they swooped down to

report the results.

They topped off their performance at this

Jap outpost by directing the fire that de-

stroyed a flotilla of enemy barges loaded

with soldiers sent to reinforce the garrison

holed up in Bloody Nose Ridge.

The first Marine airjeep outfit organized

as a squadron went into action on Guam. Under the com-

mand of Maj. Gordon W. Heritage, of Wash-

ington, D. C., it was based on a CVE, an oil

tanker converted into a carrier. The ship

lay off Guam for three days while the

leathernecks went in over the beaches. Then |

the planes took off to establish a base at an

improvised landing strip on Orote Peninsula.

‘They had to land on a makeshift runway

because air and sea bombardment had pul-

verized Agana Field, the Jap airstrip. From

3,000 feet away the Japs were lobbing shells

from mortars and spraying the area with

machine-gun bullets. The airjeep crews

slept, when they could, behind bulldozers.

Daily they flew behind the Japs’ front |

lines. Within ten seconds after they took

off they were over enemy-held ground.

Winging just over the tops of the trees,

they helped shorten the Guam campaign

by days by directing the fire of 27 batteries

of Marine artillery, each with 12 guns.

One pilot caught the glint of sun on steel |

as he flew low over the jungle. He ordered

a concentration of fire. It cost the Japs

three big guns, 60 trucks, and 400 officers

and men.

In Italy, during the European war, air-

jeeps were used to lay telephone lines be-

tween command posts and forward obser-

vation positions in mountainous country that

was hard to get to. The airjeep pilots un-

reeled wire as they flew along.

In Burma airjeeps evacuated 400 wounded

British and Indian soldiers cut off by the

Japs on the Arakan front. From a hastily

built landing strip they had to fly nearly

1,000 miles in short hops back to their

home base.

In Algiers, an airjeep pilot sighted a herd

of gazelles roaming the countryside behind

the coastal hills. He organized a hunting

party and dropped several of the animals

with rifle fire from the air. A retriever in

a ground jeep collected the meat. Camp

cooks featured ‘gazelleburgers” on the

menu.

One airjeep was credited with downing a

Messerschmitt fighter. When the Nazi got

on his tail the airjeep pilot flew into a dead-

end ravine. Turning in a circle hardly wider

than the span of his own wing, the Ameri-

can pilot watched the German, unable to

maneuver out of the hole he had bungled

into, crash.

For two months airjeeps were used to

keep traffic rolling on the congested ‘Red

Ball Express” highway line between Cher-

bourg and Paris before American engineers

got the French railroads into operation.

Cruising back and forth above the narrow

ribbon of pavement, they radioed word of

traffic jams to the engineers charged with

keeping trucks moving.

The versatility of these lightplanes was

proved anew by Lt. Col. John C. L. Adams,

an infantry officer, during the invasion of

southern France. Twice he landed behind

the German lines in an airjeep to make

personal contact with the commanding of-

ficers of units that had been cut off.

Occasionally, airjeeps were fitted with

bazooka barrels on the under surface of

their wings, and the pilots attacked extra-

tough enemy gun positions with rockets. A

variation of the installation is a small bar-

rel platform on each wing strut. The ba-

zookas are fired with lanyards. One pilot

on the European front killed off targets as

big as German Tiger tanks (P.S.M., Feb.

45, p. 84).

The Germans, British, and Russians have

used their own types of airjeeps in a

variety of ways. It was a slow German

plane of exceptional performance, called

a Storch, that snatched Mussolini from Al-

lied captivity. Both the Germans and the

British used lightplanes to land saboteurs.

Red Army lightplanes were used to string

parachute flares that guided tanks to weak

spots in the German lines during the cam-

paign in the southern Ukraine. The Rus-

sians arm their airjeeps. They used them

for bombarding German artillery positions.

Fast thinking by a grasshopper pilot

probably saved the life of Gen. George S.

Patton in a close call on the European

Front. “Old Blood and Guts” was taking a

look at the battlefield from a small liaison

plane when a German fighter dived at it with

all guns blazing. Patton's pilot dropped the

grasshopper to treetop level, and the Nazi,

unable to pull out of his dive, crashed in

flames.

~ Alrjeep crews are proud of their outfits

and their planes, and they sometimes look

on the exploits of men who fly bigger,

heavier planes with an ironical humor. One

squadron in Italy organized a “bombing”

mission of eight planes. The ammunition

consisted of five-gallon tins of gasoline.

Over the target, a German airfield, they

solemnly unloaded their “bombs.”

Back on their home field they wrote a re-

port: “We failed to shoot down 120 enemy

planes. We did not obliterate the target,

and, despite flak which was not thick enough

to walk on, we did not start fires visible for

80 miles.”

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Devon Francis (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1945-07

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

94-97,210,214

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 147, n. 1, 1945

Popular Science Monthly, v. 147, n. 1, 1945