-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

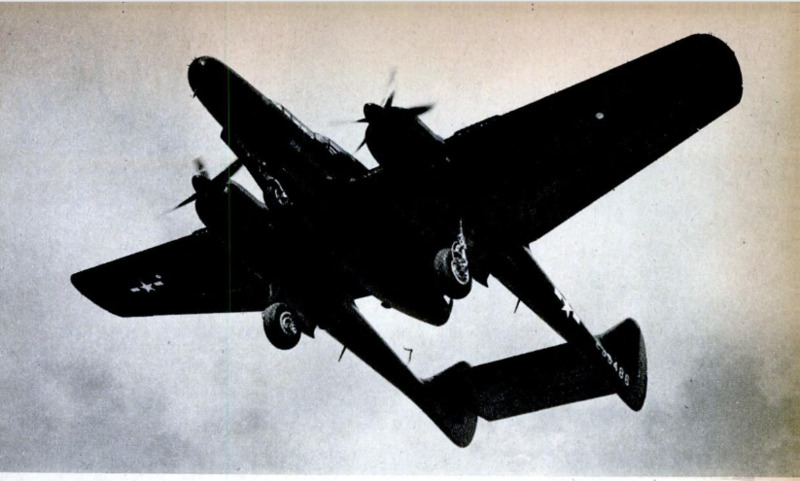

My sweetheart is a black widow

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

My sweetheart is a black widow

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

THAT Jap pilot tooling his twin-engine

Dinah Mark II toward our airstrip at

Morotai wasn't worried. At 8,000 feet his

fighter was invisible (he thought), his

20-mm. cannon and 7.7-mm. machine guns

would protect him in a clinch, and as a last

resort he could climb a mile in 90 seconds

or so to evade us. g

"He hadn't the foggiest notion that Lt.

Phil Porter and I were floating in the

moonlit night over the field, throttled to

minimum cruising. We were saving gas,

to make sure we'd have plenty in case a

Nip came over.

He still wasn't worried when our ground

control picked him up and flashed the first

order: ‘“Darkie One from Nightie. Climb

to 8,000 . . . course two zero zero . . .

range about 12 miles.” Instantly I turned

my attention to my instruments. Phil

shouted instructions as I swung the Black

Widow onto the new heading. I flipped on

the water injection to pull another six

inches of manifold pressure. That meant

200 to 300 more horsepower from the big

Pratt & Whitneys . . . 300 feet a minute

faster climb.

While ground control continued direct-

ing us toward the incoming fighter, I

climbed and turned with everything jammed

to the fire wall. The Jap was headed for

our field, bearing a load of medium bombs.

A few more seconds, and we spotted each

other in the brilliant moonlight, at a range

of 2,000 feet. He then was within a mile

of our base.

Talk about evasive action! That boy

could fly: He was worried now, for the

Nips had heard about these deadly Black

‘Widows. Ours were fairly new, but those

four 20-mm. cannons spouting flame and

shells from the belly spelled certain and

swift destruction to any fighter or bomber

within range.

I could see him easily as he climbed. His

maneuver was no good, for the Widow was

climbing even faster. I began overhauling

him at 17,500. Three bursts failed to hit.

The fourth and fifth seemed to do little

damage. For the sixth I managed to pull

in within 150 feet of his left wing and cut

loose with a full deflection shot as he

roared past. Chunks exploded from the

glistening Dinah. He fell, burning, a plume

of smoke following him to earth.

This was not my first kill. Some time

earlier, while flying a P-38 Lightning over

Jap-held Alexishaven, New Guinea, on dusk

patrol, T had picked off a Val dive bomber

as the plane was about to land. Three

bursts of about 150, 30, and 20 rounds

blasted its crew to their honorable an-

cestors. But now the Black Widows were

beginning to arrive. Here we had the first

American plane specially designed for night

fighting. With it we could do things under

cover of darkness that we dared not at-

tempt with other types.

Three weeks later, while flying a Light-

ning, I snagged on successive nights a

probable, one Betty, and a probable. The

Betty is a twin-engine medium %omber

similar to our Mitchell. Shooting down a

Betty from a P-38 isn't like smashing one

from a Widow in complete darkness.

Searchlights picked her out and held her

for me, and I ran her down after she had

unloaded her bombs on Morotai. She

couldn't climb like the Dinah, so I got her

with two bursts from directly behind as

we screamed down. My air-speed meter

indicated 475; actually it was much more.

Betty began to burn as I shot past, and

cartwheeled into the water offshore.

Shooting down Nips at night gives you a

grim satisfaction unmatched by daytime

victories. Aided by detection

equipment, you can stalk them as

a tiger stalks its prey and blast

them into the beyond, frequently

before they know you're tailing

them.

For the record, the Widows

have “killed” nearly every plane

shot at since they first started

west from the Northrop plant in

California in June 1944. Not one

Widow has been lost, at this writ-

ing, to enemy action in the

Pacific. I know of only one to be

missing on a mission, and 1 have

fairly good reason to think that its

crew ditched near the Philippines,

and that they are safe today.

I was skeptical of the first Black

Widow T saw. “She's awkward as

a hox kite,” I remember thinking.

“She's too big and clumsy to be a

fighter.” But when you make high-

speed stalls into a dead engine, in

the dead

of night; when you can climb away from

the Tonys, Tojos, and Franks and turn with

‘em; when she always brings you home

from dangerous lone-wolf intruder missions;

and when you know her cannons will knock

out of the sky anything that flies and never

jam—brother, you've got an airplane that’s

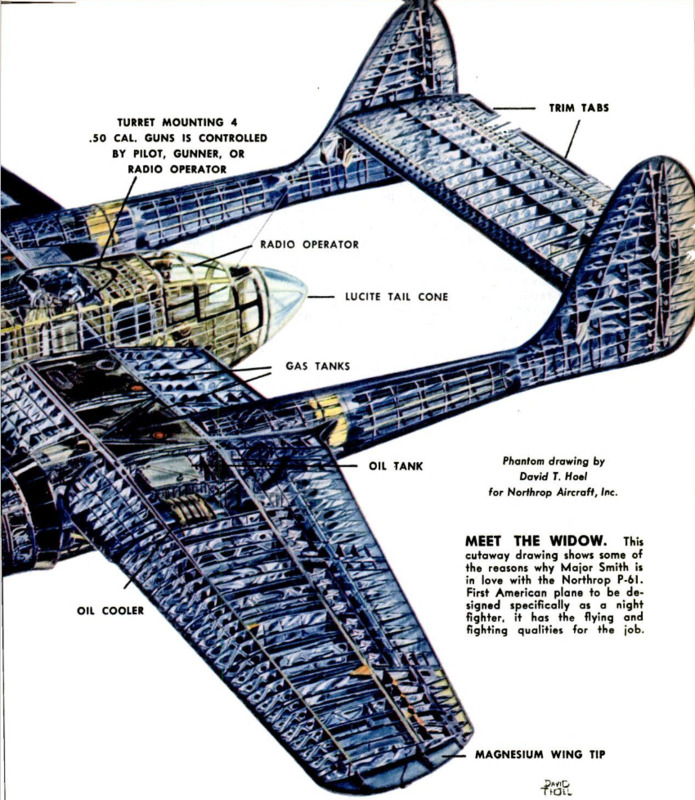

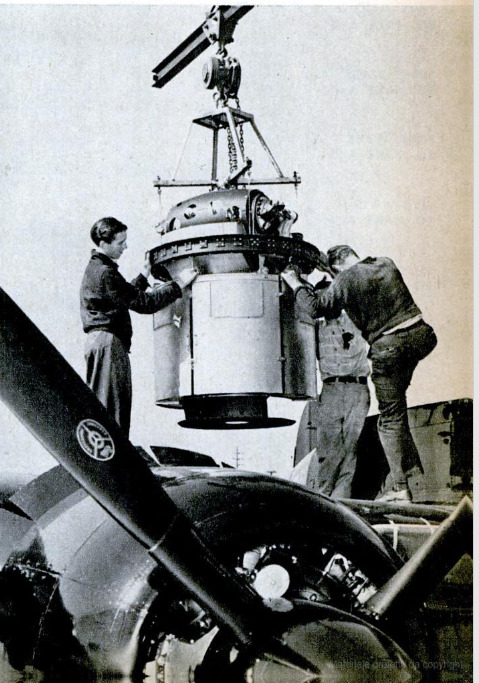

both safe and deadly. (Not until recent

weeks did Black Widows carrying four .50

caliber machine guns in the top turret

reach our squadron.)

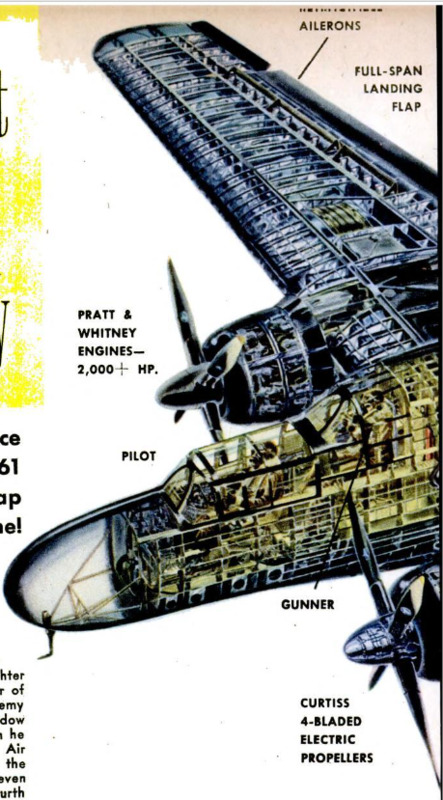

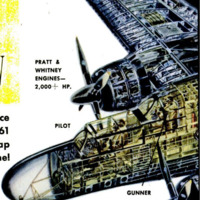

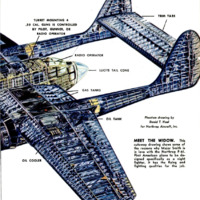

Only in a plane designed and equipped for

the purpose is the specialized and compara-

tively new operation of night fighting cer-

tain of success. The Widow carries in her

two engines more than 4,000 horsepower—

as much as a Diesel locomotive. Full-span

flaps shorten take-off and landing distances,

50 we can operate from short fields, under

fire. Retractable ailerons of the spoiler type

shorten the turning radius and give us easy

control at high speeds. Elevator booster

tabs, unusual on a fighter, make it easier

to actuate controls, especiaily in tight, steep

turns. Usually, we need all their aid when

winging away to protect a convoy or to

stop the Jap before he can blast our own

installations with machine guns and bombs.

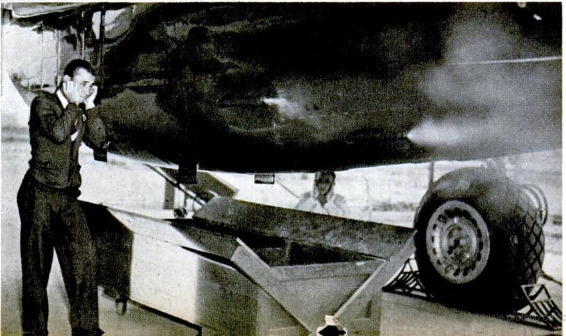

No telltale tracers stream out from our

guns. We make ourselves as inconspicuous

as possible. We sneak in, kill, and run. By

sneaking and striking, my squadron of 12

planes bagged 14 Jap planes in 11 nights

over and near Mindoro, in the Philippines.

Four of these, as luck had it, were mine—

all shot down in a single night.

‘We moved from Morotai to Mindoro the

day after Christmas to protect a new air-

strip and cover invasion convoys moving

north to Luzon. Gunfire from a Jap naval

task force drove us away that night. I

hovered over the Jap ships until long after

midnight, keeping up a Clem McCarthy

running account so that the B-25's and

B-24's of the Fifth Air Force, and day

fighters acting as dive bombers, could drop

their loads on the best targets. Gas low, I

pulled out to land at Valencia, near Ormoc,

on Leyte on a grassy strip illuminated

briefly by the lights of jeeps parked along

the edges.

Early in the morning, I flew on to Taclo-

ban, where I found the rest of my squad-

ron's planes and crews safe. After refuel-

ing, we returned to Mindoro to take over

night patrols and night convoy cover. At

dusk and dawn, four-plane flights patrolled

in regular fighter formation off the fringes

of the convoys. Two patrols protected our

base. After darkness fell, single plane flights

covered the convoys. Even in the moon-

light, the hundreds of ships seemed to

stretch beyond the horizons, a mighty por-

tent of trouble brewing for the Japs on

Luzon. We really pushed ‘em those nights.

The squadron's planes averaged 10 hours in

the air. We flew halfway around the world

every night.

With more than 100 night missions be-

hind me, I long ago had overcome my dread

of lack of vision. You don't fly these killers

by the seat of your pants. You trust to

your many instruments. I placed utmost

confidence in both the plane and the instru-

ments. You've got to trust ‘em when the

radio's silent, and you're up there in a void

weaving around the sky three and four

hours. It's a monotonous, lonely job—but

fairly safe if you keep a cool head. The

job, as the British say, calls for “dash with

discretion.”

Theoretically, you never shoot down an

enemy plane by instruments alone. You

need visual contact. On a bright, moonlit

night, T found I could see a Jap plane a

half mile away. When clouds or storm ob-

scured the moon, I've sneaked up within

200 feet of a twin-engine bomber without

being sure whether he was friend or foe.

If he didn’t reply with the proper code to

our signal, it was “Katy bar the gate.”

Something awful would happen.

Business proceeded as usual until the

night of January 7. That's when the can-

nons of my “Time’s-A-Wastin'” got four—

two Irving bombers, a float recon plane,

and a Frank.

Three of us took off shortly before dusk

and flew 50 miles south to cover a convoy

of 300 ships. Thirty minutes after the light

began to fade, I sent my two wing planes

back, and continued my patrol alone. It

was perhaps an hour later when the fighter

director ship messaged: “Indications plane

coming from southwest—8,000 feet—12 to

15 miles away.”

1 set a collision course, climbing and hop-

ing to intercept the Jap at a safe distance

from the convoy. I closed in fast, and first

saw him two miles away, scudding toward

a cloud. Both Phil and I identified him in-

stantly: An Irving, similar to a Nick, only

slightly larger. A deadly 20-mm. stinger in

the tail, and three 12.9-mm. machine guns.

Mustn't let him get in the first burst.

For seven minutes I chased the fellow.

He turned in and out of the clouds. Grad-

ually we descended. I hit him with a short

burst as he entered one patch of cloud, and

got away a second burst, the bullets striking

around the wing roots, when he came out

in a turn, His tail stinger was chattering,

but not for long. Down he dived, burning,

to disappear completely.

The Irving was swallowed by the sea at

nine o'clock, straight up. We circled only

long enough for Phil to confirm the kill T

headed west, climbing to patrol altitude of

8,000 feet, to place myself off the west side

of the convoy once more. Within a couple

of minutes Phil spotted another one. “About

11 o'clock,” he grunted. “Same altitude.” I

swung the plane a needles width or so.

Then I saw him, another Irving, etched

against the moon.

He was so close to the convoy I had no

chance to maneuver for a tail shot. I

opened her up wide, in a head-on approach,

diving to cut off the Irving before he started

his bomb run. At 800 feet I cut loose with

a three-second burst. Slugs bit into the

canopy, others opened his fuel tanks. Sev-

eral pieces flew off. The plane tumbled

1,500 feet and blazed merrily as it glided

into the water.

By now, our gas was dangerously low.

We landed to fuel, grab a cup of coffee,

and snatch forty winks. The ground crew

had no time to rearm the guns, but I figured

we had maybe half the 700 rounds we had

started with. Shortly before three we rolled

off the dark runway to patrol locally. Our

plane took the west sector. For a half hour

we sat there, 20 miles off the island, “orbit-

ing the beacon” in a 25-mile-long shuttle at

“an altitude of expectancy.” This meant

7,000, for the Japs had been coming over

at 8,000 or lower.

Two in one night was a good score, I was

thinking, when ground control broke into

my thoughts: “Smith from Barr. Start

letting down on course of three zero zero.

Level off at three thousand.” Minor changes

came through rapidly: “Take course three

Wo zero . . new course zero six zero.” The

Jap apparently was coming from the north,

offshore. Ground control was bringing me

toward the coastline for an interception.

“Course two seven zero . . . let down to

1500 feet.” Now Phil took over. “Let

down,” he shouted. “Steady . .. right...

steady . . . haul off the coal!”

1 throttled back. I had overshot. It was

like trying to catch a greased pig. I almost

had my guns on a Rufe, a single-engine

navy fioat plane. But the Widow was too

fast. For five minutes I circled over and

around him. We were down to 200 feet. He

maneuvered like mad. I'd pick him up, then

lose him in a tight circle. I could almost

see that pilot mopping his brow when I

finally caught him against a light portion

of the sky. I let the flaps half down, hoping

their drag would cut our speed to 120. He

dived, but didn't seem to go anywhere.

Then I let him have a short burst at 150

feet. His grave is unmarked.

Back once more on patrol course, I was

certain the night would bring no more ex-

citement. An hour groaned by. We had

reached the north end of the course for the

umpteenth time when the ground control

broke the monotony. Something going

north, vector zero two zero. That some-

thing, 1 learned later, had been strafing the

base. The horse had been stolen, and it was

up to us to lock the door so that particular

thief couldn't sneak back another time.

Barr put us on him at 8,000. When Phil

got a contact, T dived the Widow to 4,000,

picking up speed to catch the fleeing fighter

or bomber before he could escape ground

control's range. I first saw him in the dusk-

before-dawn 4,000 feet ahead and above us.

Gradually I approached, directly on his tail.

Phil formed a word with his lips: “Frank.”

Yep, we had a new-type fighter in our sights.

I knew the Frank could hit 400 or faster.

It's like the Zeke, but better.

Now ~ began lo worry. Three kills al-

ready. How many rounds of ammunition

had T used? Maybe I had a hundred left,

and maybe I had only two or three. T had

to get him with the first burst! Phil com-

menced calling off the ranges. When he hit

150, he peered out ahead. I could see the

Frank looming up closer and closer. I

closed to 75 feet. At that deadly range . ..

Phil says we were closer . . . I hit the but-

ton. Twenty, 30, maybe 40 tapered steel

slugs rammed into the Frank. As he ex-

ploded T chopped the throttle, dropping back

to avoid most of the debris.

Dangerous? Foolhardy? Yes, I guess

youd call it that. But I meant to get him,

and did. As it turned out, I might have

taken a longer chance by firing from a

greater distance. My crew chief reported

later we had used 380 rounds for the night.

I could have poured another 320 slugs into

that luckless Jap.

Seven victories do not add up to a large

total. That's not the real test of night

fighting. Night fighters are primarily a

defensive weapon, though they are some-

times used for train-busting and strafing

ground installations. Our real job is saving

airstrips and convoys from damage in the

dark. As T said, few Jap planes have es-

caped once they blundered within range.

That's the finest tribute I can write to the

Black Widow. She's my sweetheart.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Maj. Carroll C. Smith, (article writer)

-

Andrew R. Boone (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1945-07

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

116-119,207-208

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 147, n. 1, 1945

Popular Science Monthly, v. 147, n. 1, 1945