Tin cans dish out!

Contenuto

-

Titolo

-

Tin cans dish out!

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Tin cans dish out!

-

extracted text

-

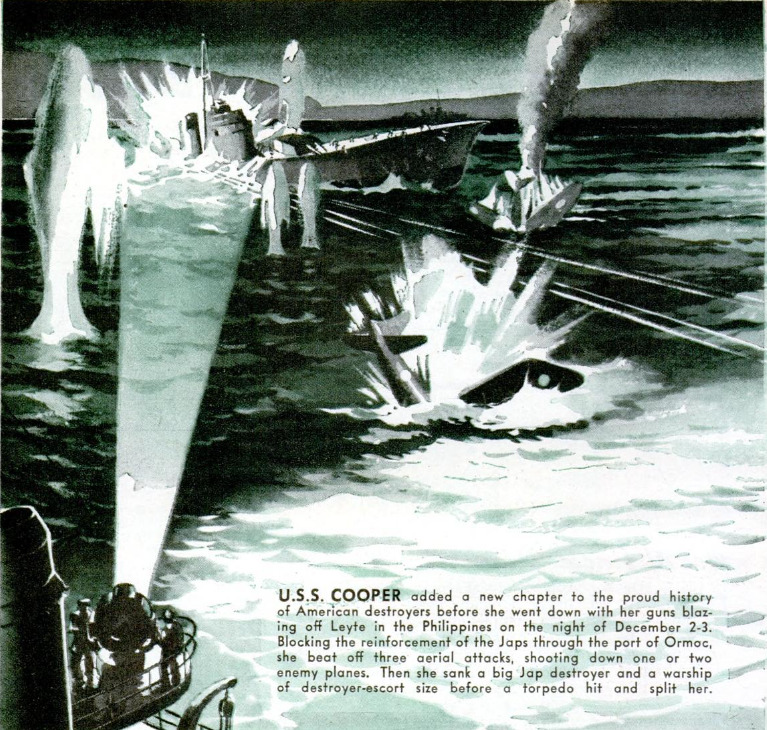

SCRAPPIEST of warcraft, they stand up

to anything afloat, including battleships.

Ton for ton, they outgun all other men-of-

war. On the same basis, the propelling ma-

chinery that gives them their dashing speed

is the most powerful. High seas inundate

their decks, they roll until masts stand mid-

way between sky and water, and sandwiches

are stormy-weather fare until pots and pans

will stay put on galley stoves. They are

about the largest warships whose men all

know each other by first names. Crews

openly blast with seafaring language, but

secretly love, these sailors’ ships that lay-

men call destroyers, that the Navy Depart-

ment lists as DD's, and that will always be

known to the men aboard them as tin cans.

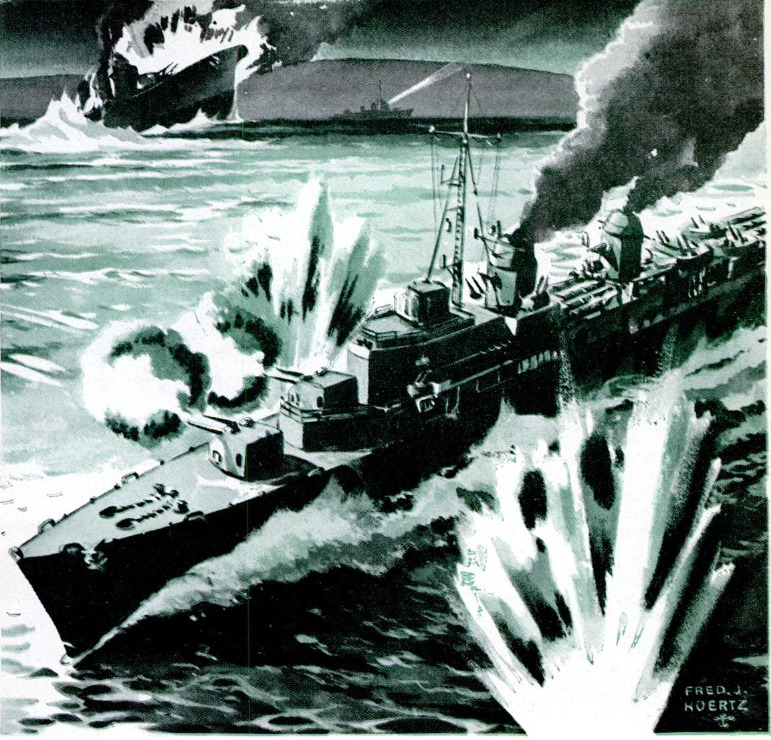

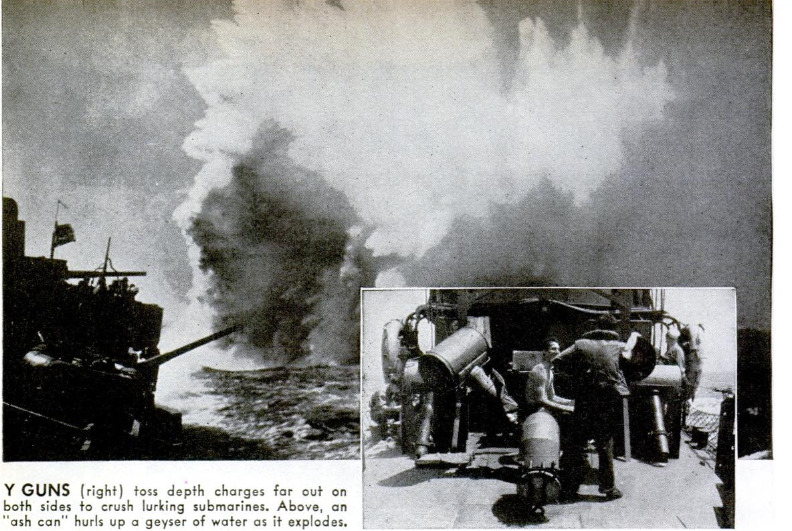

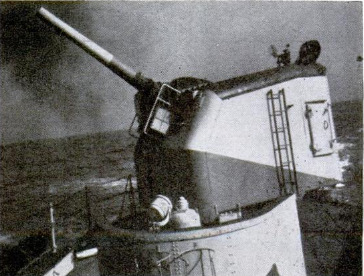

A destroyer of our 2,100-ton Fletcher

class, last on which details are available,

illustrates what a modern destroyer fights

with. Five double-purpose guns of five-inch

caliber shell surface craft, or may be ele-

vated to fire on planes. Antiaircraft guns of

40-mm. and 20-mm. size provide additional

firepower. Also double-purpose, the AA's

can be depressed to riddle surfaced sub-

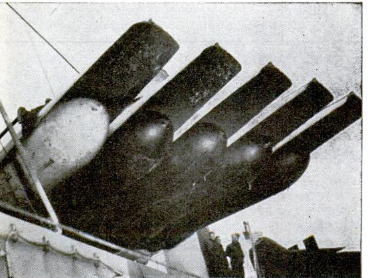

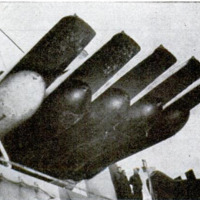

marines. Two deck-mounted sets of tor-

pedo tubes, five in each mount, invite

healthy respect from enemy warships.

Depth charges dispose of submarines under

water. Though our latest and heaviest de-

stroyers of the 2,200-ton Allen M. Sumner

class remain pretty much under wraps, it

may be said that increased armament prin-

cipally accounts for their greater tonnage.

From its guns alone, a Sumner-class de-

stroyer throws more than a ton of steel in

only 15 seconds, as Japanese warcraft have

already learned to their dismay.

As might be suspected from its variety of

weapons, a destroyer performs countless

missions. Supporting amphibious landings,

naval opinion holds, represents the outstand-

ing innovation among destroyer uses during

‘World War II. Based on such successful

tests as the Normandy invasion, in which 30

U.S. tin cans participated, the procedure

begins with a preliminary long-range bom-

bardment by battleships and cruisers. This

reduces to rubble the massive fortifications

that only their heavy shells can penetrate.

Now comes the destroyers’ turn. Able to

maneuver in shallow and constricted waters,

they steam close to shore, to locate and put

out of action all remaining gun positions

commanding the intended beachhead. Of

course, this is simply throwing the rule book

overboard, for a square hit from a six-inch

shore battery can demolish a destroyer—

which has no armor worth mentioning—as

thoroughly as a salvo from a battleship’s

big guns. But when the fate of a great in-

vading army hangs in the balance, destroy-

ers become expendable. It cost us the de-

stroyers Meredith and Glennon to put our

troops ashore at “Utah Beach” in Norman-

dy, a price well justified by the success of

the landing and the enormous over-all sav-

ing in casualties.

No heavy warship, fleet, or convoy would

dream of leaving port in wartime without

an escort of destroyers to “screen” it from

attack, especially by enemy submarines.

Task forces of destroyers also hunt sub-

marines on their own. The team which de-

stroyed more submarines than any other in

naval history consisted of the four-stacker

destroyers Borie, Barry, and Goff, operat-

ing with the escort carrier Card.

One stormy night in the North Atlantic,

-

Autore secondario

-

Alden P. Armagnac (article writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1945-07

-

pagine

-

128-130

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)