-

Titolo

-

The destroyer's weapons

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

The destroyer's weapons

-

extracted text

-

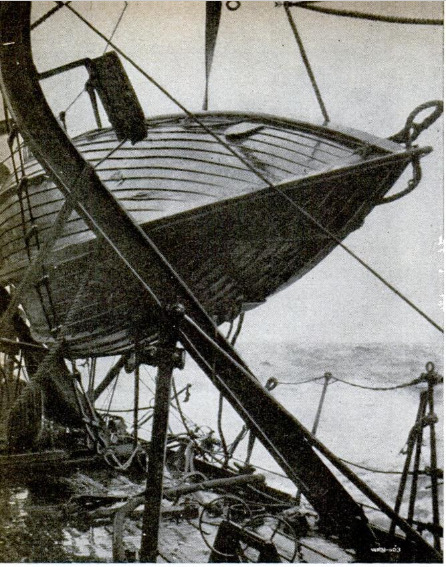

the Borie spotted a U-boat, which crash-

dived. Depth charges brought it back to the

surface, and the Borie rammed it. Freeing

itself, the sturdy submarine attempted to

torpedo the destroyer. But a well-placed

shell from the Borie carried away the U-

boat's conning tower and ended the battle.

The stern of the submarine tilted skyward,

and it nose-dived to the bottom. Severely

damaged in the encounter, the destroyer

stayed afloat only long enough for another

ship to rescue nearly all of her crew. In

memory of her valiant fight, her name has

been reassigned to one of our newest super-

destroyers.

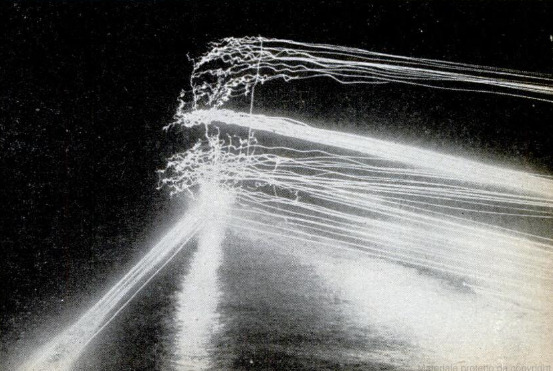

Laying a smoke screen—an important

destroyer mission—contributed to the

smashing American naval victory in

the Second Battle of the Philippines,

now officially renamed the Battle for

Leyte Gulf. When a powerful Japa-

nese fleet made a surprise sortie

from the central channel, guarded

only by our light carriers and de-

stroyers, the tin cans raced between

the opposing forces, billowing dense

smoke. Two of them, the Hoel and

the Johnston, failed to come back.

But under their cover, the carriers

were able to launch their planes,

and, having done all they could, to

retire until American reinforcements

put the bomb-battered Japs to flight.

In a full-dress fleet action, normal-

ly covering a vast expanse of sea,

destroyers do the infighting—attack-

ing enemy destroyers, cruisers, and

battleships as they charge across the

distance between the majestic lines

of big vessels. Two of our own major

naval engagements—the Battle of

Guadalcanal and the Battle for

Leyte Gulf—gave our destroyers

their chance against battleships,

though the narrow waters in which

they took place turned stately ma-

neuvers into wild melees.

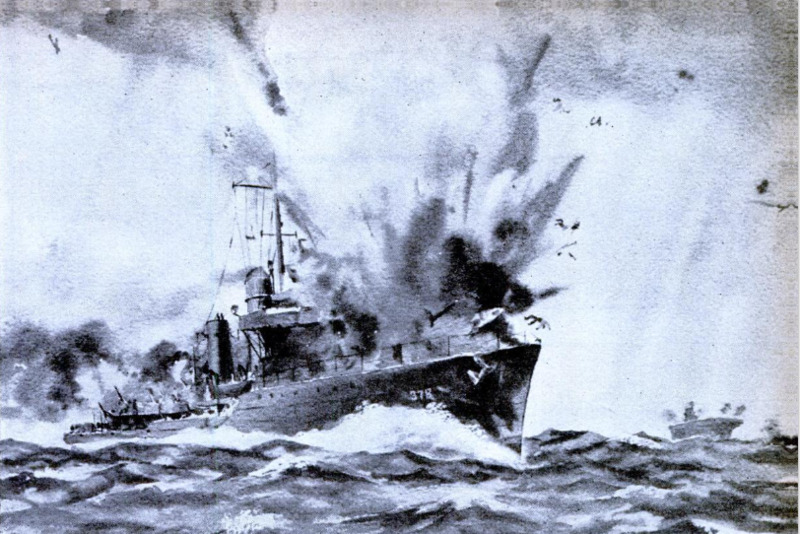

Lasting only 24 minutes, the mid-

night Battle of Guadalcanal has

been termed by Fleet Admiral

Ernest J. King one of the most furious sea

actions in history. In that time, an out-

matched American force of five cruisers and

eight destroyers repulsed a Japanese task

force of two battleships and 16 other war-

craft bent on recapturing the island from

American invaders. “We want the big

ones,” radioed the American commander,

Rear Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan. So the

destroyer Laffey, having put a Jap cruiser

out of action, fired two torpedoes into a bat-

tleship—and then, cutting past its bow,

raked it with gunfire and blew off its bridge.

Unable to depress its guns, the Jap had no

reply to this American impudence until the

Laffey put one destroyer out of commission,

blew up another, and then was sunk by bat-

tleship fire. Meanwhile several other U.S.

destroyers scored torpedo hits on battle-

ships, the O'Bannon being credited with

three.

It was also before daybreak when a

Japanese force headed by two battleships

attempted to traverse the southernmost

channel through the Philippines, in the

three-ring Battle for Leyte Gulf, last Octo-

ber. At this point, Vice Admiral J. B. Olden-

dorf was ready for them. Since the narrow

channel of Surigao Strait gave him little

room to deploy his destroyers, he lined them

up along the shore, backing up this advance

force with cruisers and battleships. Steam-

ing squarely into the trap, the Japanese

vessels suffered three co-ordinated destroyer

attacks with torpedoes, and salvoes from

our heavy ships then finished off the two

Japanese battleships and virtually the en-

tire contingent.

Just how a destroyer aims and fires its

torpedoes, by the way, makes an interesting

contrast with undersea boats. Submarines

discharge them under water, with com-

pressed air. But it takes more than a Whiff

of breeze to toss overboard a Mark 15 de-

stroyer torpedo, more than 20 feet long and

weighing 3,400 pounds with its war head of

TNT. So the torpedo gets its start from an

“impulse charge” of black powder.

Sitting astride a bank of tubes, a torpedo-

man’s mate re-

sponds to the order “Stand by to fire” by

turning a training wheel, keeping the tubes

in line with a red arrow. Above him in the

fire-control tower, the torpedo officer plots

the relative speed and course of the enemy

ship and his own. Then he presses a firing

key, and the torpedo leaps from its tube.

It has been preset to travel at a depth that

will do the most damage to_its target—

which might be five to 10 feet for another

destroyer, or at least 20 feet for a battleship

or aircraft carrier. On striking the sea, it

automatically submerges to this level, and

gyro-controlled rudders hold it on an abso-

lutely straight course up to 6,000 yards,

driven by its compressed-air motor and tiny

twin propellers.

Early in the war, a division of U.S. de-

stroyers, with one lone torpedo left among

the four vessels, had the disconcerting ex-

perience of meeting a Japanese cruiser and

its destroyer escort in the Java Sea. In-

stead of being able to attack, the American

force was in danger of being sunk, if the

Japs guessed its plight. So its commander

ordered impulse charges to be fired in empty

tubes, giving the same flash that the enemy

would see if they were on the receiving end

of real torpedoes, The bluff worked, and the

ships of the Emperor turned tail.

Ask a veteran destroyer commander

when he has come closest to death, as the

writer once did, and he replies with a grin,

“All the time.” Odd jobs that destroyers per-

form often are as perilous as fighting. The

U.S.S. Maury, whose battle log reads like

a history of Pacific warfare, served as a

tugboat in the midst of the last Japanese

naval attempt to reinforce the Nips on

Guadalcanal. Taking the disabled cruiser

New Orleans in tow, the Maury brought her

to safe waters through hostile fire and, be-

cause of reduced speed, imminent risk of

submarine attack.

When waterlogged survivors from sunk-

en warcraft are fished from the sea, de-

stroyers usually are the rescue ships. A tin

can is anything but spacious, yet the Fletch-

er—normal complement about 250—some-

how managed to take aboad 700 officers and

men from the sinking U.S. cruiser North-

ampton during the series of Solomon Island

sea engagements.

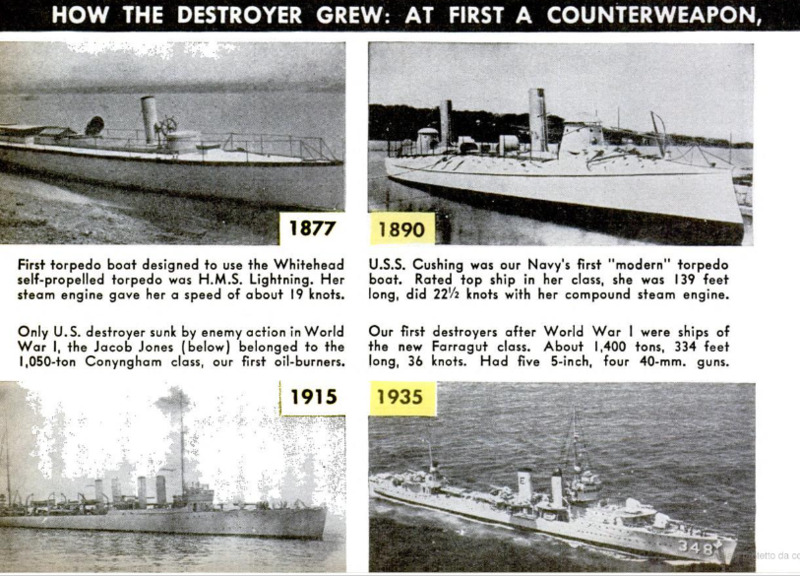

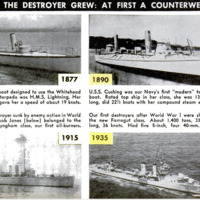

When strategists set forth to show that

every war weapon meets its match in a

counterweapon, their favorite example is

the torpedo boat versus the destroyer. Away

back in 1860, admirals of the world’s great

naval powers were scared stiff by the inven-

tion of the Whitehead self-propelled tor-

pedo. Their peace of mind was by no means

restored when Britain, in 1877, built the

first torpedo boat to use the new weapon

effectively. The steam-driven, 85-foot H.M.S.

Lightning attained what was then the high

speed of 19 knots, and carried a torpedo

tube in its bow. Other countries adopted the

innovation, and by 1890 the U.S. Navy

possessed the 139-foot, 22%-knot torpedo

boat Cushing, regarded as the top ship of

her class.

What good were mighty armor-clads,

long-time rulers of the seas, when craft of

such insignificant size could sink them?

Fuel was poured on the controversy when,

during the Chilean civil war of 1891, a

cruiser was sunk by a Whitehead torpedo.

The man with the answer was Sir William

White, chief constructor of the British

Navy. He proposed to build ships similar to

torpedo boats but enough faster and more

heavily armed to sink them. The result was

the world's first torpedo-hoat destroyer,

HM.S. Havock, a 180-footer of nearly 27

knots, armed with one 12-pounder, three

quick-firing six-pounders, and three torpedo

tubes. An immediate success, the ship was

followed by the first U.S. torpedo-boat de-

stroyer, the 210-foot, 273-ton U.S.8. Farra-

gut, which attained more than 30 knots—a

record speed for reciprocating engines.

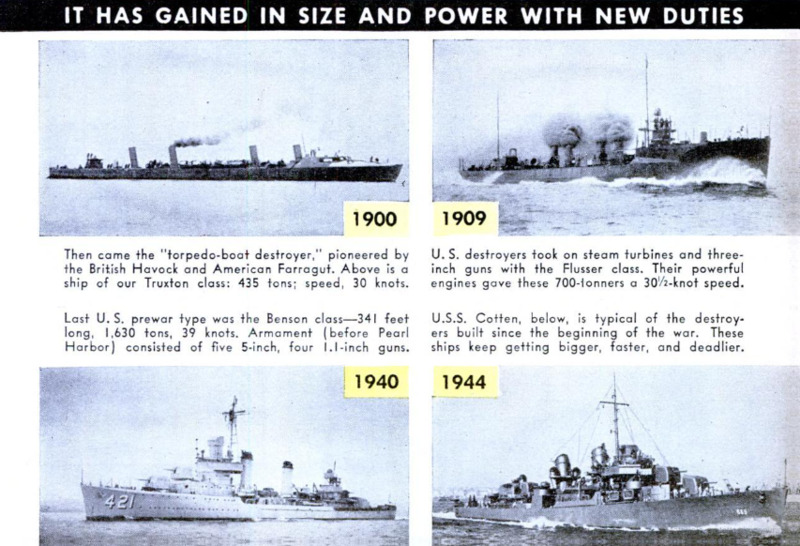

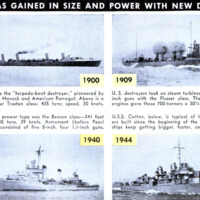

From the turn of the century on, engi-

neering improvements came in rapid suc-

cession, and destroyers—having lost their

longer name as they became major warships

—gained in size and power. Our Truzton

class of 1900 were 435-tonners. By 1909 our

Flusser class, first American turbine-driven

destroyers, and first to mount three-inch

guns, displaced 700 tons. The first U. S. oil-

burning destroyers, the Conyngham class of

1915, tipped the scales at 1,050 tons.

First to follow World War I, a new Farra-

gut class of 1934-5 consists of 1,400-tonners,

334 feet long, armed with five 5-inch and

four 40-mm. guns. Our last prewar destroy-

ers, the 1,600-ton Benson class of 1940-1

now are supplemented by the 1,700-ton

Bristols, the 2,100-ton Fletchers, and the

2,200-ton Sumners.

Formerly, the limited cruising range of

destroyers held back all the rest of the fleet.

How we are currently able to pound at the

gates of Tokyo can now be told. One means

has been the fuel-saving use of high-tem-

perature, high-pressure steam, first intro-

duced in the U. S. Navy by destroyers of the

Mahan class between 1936 and 1940. But

perhaps the most important innovation is

that of seagoing supply and repair bases.

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1945-07

-

pagine

-

131-134,203

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Screenshot 2023-01-19 172021.png

Screenshot 2023-01-19 172021.png Screenshot 2023-01-19 172032.png

Screenshot 2023-01-19 172032.png Screenshot 2023-01-19 172044.png

Screenshot 2023-01-19 172044.png Screenshot 2023-01-19 172054.png

Screenshot 2023-01-19 172054.png Screenshot 2023-01-19 172105.png

Screenshot 2023-01-19 172105.png Screenshot 2023-01-19 172120.png

Screenshot 2023-01-19 172120.png Screenshot 2023-01-19 172132.png

Screenshot 2023-01-19 172132.png Screenshot 2023-01-19 172144.png

Screenshot 2023-01-19 172144.png Screenshot 2023-01-19 172159.png

Screenshot 2023-01-19 172159.png Screenshot 2023-01-19 172210.png

Screenshot 2023-01-19 172210.png