-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

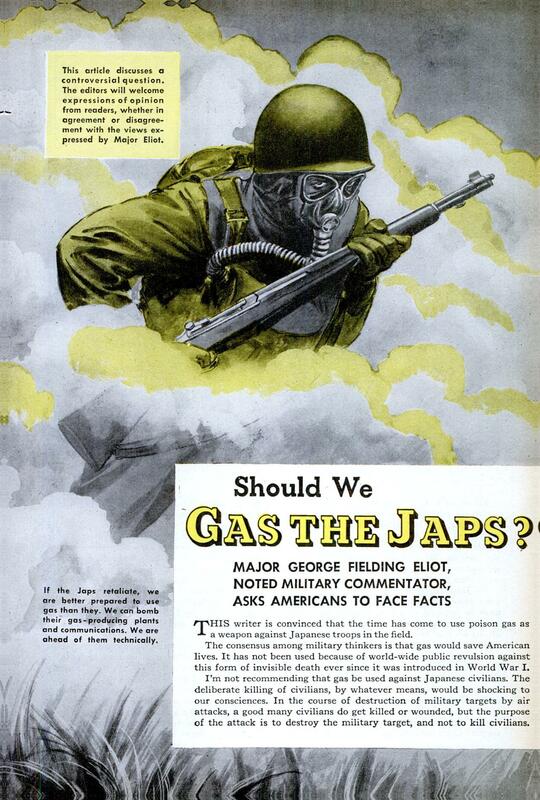

Should we gas the Japs?

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Should we gas the Japs?

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

THIS writer is convinced that the time has come to use poison gas as

a weapon against Japanese troops in the field.

The consensus among military thinkers is that gas would save American

lives. It has not been used because of world-wide public revulsion against

this form of invisible death ever since it was introduced in World War I.

I'm not recommending that gas be used against Japanese civilians. The

deliberate killing of civilians, by whatever means, would be shocking to

our consciences. In the course of destruction of military targets by air

attacks, a good many civilians do get killed or wounded, but the purpose

of the attack is to destroy the military target, and not to kill civilians,

There isn’t any international agreement to

which we are a party which bars us from using

poison gas. The last attempt at such an agree-

ment was made at Geneva in 1926, as a part

of the disarmament discussions. It was called

the Geneva Gas Protocol. But the U. S. Senate

refused to ratify it. Nor did Japan ratify it. So

we're clear on that point.

All Japanese hopes now are centered on the

price they can make us pay for victory. They

have no hope of regaining the offensive. Their

sea and airpower have been so reduced as to be

of little more than nuisance value. But they

have a strong army, composed of tough, hard-

bitten soldiers who know how to die; and they

have a defensible terrain which gives every

opportunity for stubborn yard-by-yard defense.

Few parts of Japan are far from mountains or

really distant from the sea. Their foot soldiers

and their terrain are the two main factors in

their defensive armory. So their strategy is

simple: Come and get us, and see what it will

cost you! It is the only strategy that is possible

under the circumstances.

The Japanese, in other words, have lost the

war but must yet be made to admit it. Doing

this may cost tens or hundreds of thousands of

American lives, and infinite suffering from

wounds and permanent disablements, if we have

to take Japan yard by yard as we have taken

Iwo and Okinawa. Iwo consists of only about

eight square miles, but it took us 26 days to

conquer that tiny island, and 4,189 Americans

gave their lives and 15,308 were wounded in

the process.

Under these conditions, we must certainly

ask ourselves whether it is not time to consider

once more, and very carefully, the use of chemi-

cal agents to end this war.

For some reason that I cannot comprehend,

the use of gas in warfare seems to shock the

average mind. We accept the use of incendiary

agents against Japanese cities, though we must

be perfectly aware of the extent and nature of

the casualties thus caused. We accept the use

of high explosives in all forms. We accept the

motion pictures that show us flame-throwing

tanks going into the attack on Japanese posi-

tions. But we shudder if anybody says “gas.”

Apparently, it is more humane to kill people

with third-degree burns, or by smashing their

bodies by shellfire, than it is to asphyxiate them;

apparently it is morally all right to burn them

up with flame, but wrong to sear their hides with

mustard gas. 1 don't know why, but that's the

way many people feel about it.

Let's translate this, however, into terms of

American lives and see how it looks. Let’s take

a test case: Okinawa. This island is only 67

miles long and has a maximum width of only

10 miles. But conquering it took nearly three

months and 45,029 casualties, because we had

to root out the Japanese from a terrain deeply

indented by valleys and gullies, pock-marked

with caves, and further protected by all sorts

of artificial defenses, including deep shelters,

trenches, and covered lines of communication.

We brought to bear against these Japanese

defenses the heaviest sort of concentrated fire —

by aerial bombardment, naval gunfire, artillery,

machine guns, and mortars. We proved once

more what every soldier knows: you can’t shoot

well-dug-in infantry out of positions. You have

to go in and drive them out with bayonet, rifle,

and grenade. You get a lot of your own infantry

killed doing this.

This sort of terrain prevails over most of the

Japanese islands. Japan proper has an area of

147,889 square miles, and is traversed by lofty

ranges, with summits separated by low passes

and valleys. The Japanese, in defending Okinawa.

to the last, were in effect saying to the American

people: Look at what one little island is costing

you! Are you going to pay a proportionate price

for the whole of Japan, piece by piece?

The problem will be much the same. We can

isolate one piece of Japan after another. We

can knock out the Japanese guns and tanks.

We can shoot their planes out of the air. But

we still will have to go in and dig out their

infantry — and pay the price.

Would gas help us do this job? Would it

reduce American casualties appreciably? There

can be very little doubt that it would do so.

Persistent gases are heavier than air. They sink

into valleys, caves, and deep shelters. They

reach men in positions that are perfectly pro-

tected from the blast of high-explosive shells.

They are especially adapted for just the type of

warfare with which the Japanese are now con-

fronting us.

Gas is no more the perfect weapon than high

explosives or fire. It has limitations, just as all

weapons have. It will not win the war by itself.

But it will enable us to win it at far less cost

in time and casualties.

If we use gas, of course, the Japanese will use

it, too. But the Japanese are far less technically

and industrially prepared to use gas than we are;

and their means of producing and transporting

it are subject to direct attack, to which the

Japanese cannot reply in kind. We can bomb

their gas-producing plants, the railways by

which they transport gas to the front, and the

depots behind the front in which they assemble

gas and the appliances for using it. The Japanese

are too weak in the air to do the same to us.

Would the Japanese use gas against Chinese

civilians if we used it against Japanese soldiers?

Very likely they would if they could. But the

effective use of gas is a weight-carrying proposi-

tion, and the Japanese do not have a weight-

carrying air force. They have, in fact, almost no

heavy bombers. The use of their medium

bombers to attack Chinese cities with gas would

be about as uneconomical a waste of effort as

could be imagined.

As for Japanese defensive measures, of course

they would do what they could. There is good

reason to believe that long immunity has caused

them to neglect their gas defense. Gas masks

captured in Burma and the Pacific in recent

months have been found useless because the

chemical “filters” had not been renewed. The

“gasproofing” of caves and underground defenses

is not easy, especially for a country whose

industrial plant is under heavy attack. It would

be very difficult for the Japanese to produce

something new in great quantities,

I can think of no good reason, on strictly

military grounds, why gas should not be used.

It is hard to say whether there is a psychological

or moral reason. Would our people and our allies

react unfavorably? It is hard to believe that

they would if the saving of lives was made clear

to them.

The Japanese have lost the war. The thing to

do is to get the fighting over with, to convince

the military fanatics that they must give in,

and to do this without losing any more of our

young men than is necessary. I believe the case

for the use of gas now is a strong one,

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1945-08

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

49-53

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 147, n. 2, 1945

Popular Science Monthly, v. 147, n. 2, 1945