-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

When the AAF throws

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

When the AAF throws

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

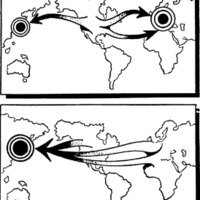

FOR the big job of moving our airpower

from Europe to the Pacific, an AAF engi- |

neering officer said, “We've got to have the

land. Then the bases have to be laid out and

carved out. On these airdromes and back

of them, we have to set up depots of various

sizes. Next comes the equipment for the

service units, and the stockpiles of matériel

and housekeeping items. Fuel comes in.

‘Then, and only then, are we ready to bring

in the planes.”

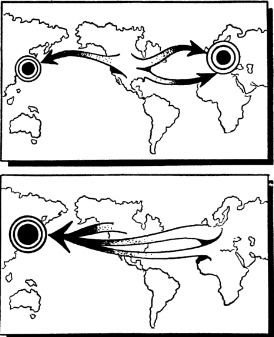

It is a transplanting operation of global

proportions that involves every type of con-

veyance that moves on land, on sea, and in

the air. And in carrying out this “bulk re-

deployment” of the AAF we had to start

from scratch. We have not the land, the

facilities, or the supplies on the scene, such

as were available in England under reverse

lend-lease; and, with the exception of China,

there is no ally in the Pacific from which we

can draw on local civilian help. Every sin-

gle pick and shovel, screwdriver, gasoline

drum, and box of rations must be sent from

either Europe or the U. S. Either way, it is

nearly halfway around the world.

The planning for this tremendous task

began in Washington

almost a year before

the Germans surren-

dered. Commencing in |

the offices of the Joint

Chiefs of Staff, the |

Army-Navy Logistics

Board, and Gen. “Hap” |

Arnold of the AAF,

these plans coursed

through channels all

the way down to Joe

Doaks and Mary

Smith, who sort rivets

in some two-by-four |

plant of a subcontrac- |

tor in the alley back

of Main Street. |

The elaborate plan

calls for the moving |

of everything but the |

bases. Even the Army |

and Navy cannot bulk- |

redeploy airdromes, |

and these must be pre- |

pared and equipped

in order that the re-

deployed AAF will have somewhere to go

when it arrives in the Pacific.

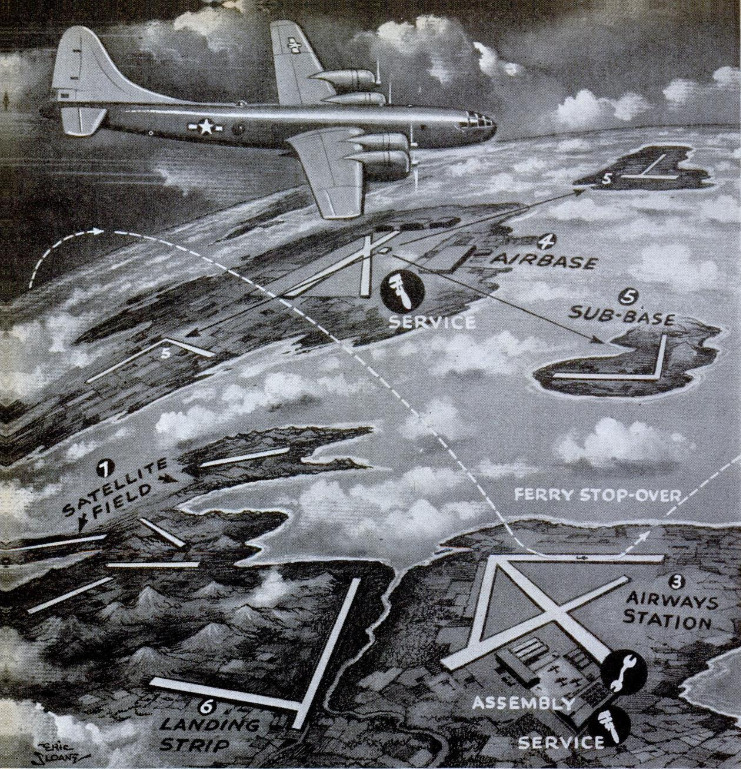

That is why the redeployment of aviation

engineers, technicians, and some air units

was under way when V-E Day arrived. The

tactical demands of the Pacific areas make

it necessary for these engineers—who will

be aided by Navy Seabees—to lay out, build,

and equip seven different kinds of air in-

stallations. These are described in the order

in which they will be used to make possible

the redeployment:

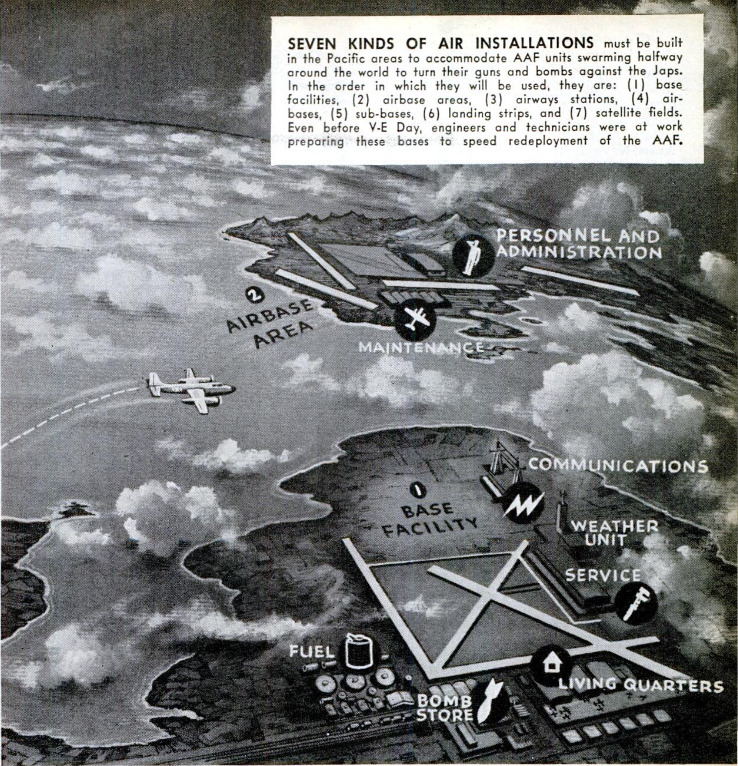

Largest are “base facilities” that include

service units, four-echelon depots, under-

ground storage for fuel and bombs and other

ammunition, weather and communications

units, and living quarters. They will take

on the aspect of regular staging areas.

“Airbase areas” will include a number of

landing strips or dispersal areas, and on

these will be located personnel and facilities

for administration, maintenance, supply, and

salvage.

“Airways stations” will be large air-

dromes with complete servicing facilities,

which will be used, primarily, as stopover

points for ferried planes. Some of these may

be used for the assembly of processed planes

that have been shipped.

“Airbases” are somewhat smaller and are

equipped with sub-depot or service squad-

ron shops. The commanding officers of these

may also have under

their control alternate

‘‘sub-bases.”

“Landing strips” are

located in forward

areas for purely tac-

tical operations. Sev-

eral of these, widely

dispersed, constitute a

“satellite field.”

The redeployed en-

gineers who are build-

ing these, or enlarg-

ing existing facilities,

all over the Pacific

area carried with them

only the most essen-

tial equipment. Every-

thing that they re-

quired was sent direct

from the U. S. and

cleverly scheduled and

routed so as to reach

the respective points

at the same time as

the men from the ETO

and Mediterranean.

This “marrying” of men and matériel is the

most intricate single phase of our redeploy-

ment scheme.

For example, the flow of matériel to Eu-

rope was so strong that we began last Oc-

tober to close the valve of this pipe line. In

anticipation of the surrender of the Nazis

and the possibility of having to reroute the

shipments of aircraft and other weapons to

the Pacific, a coding scheme was employed

to govern ship movements and loadings.

Some vessels were marked “STO,” meaning

that they were to be stopped enroute in the

event of the war's end in Europe. Others

were labeled “SHP” to indicate that they

would carry cargo that would be needed in

any event. But many of these carried planes

and parts. The other cargo was unloaded,

but the planes were shipped back- to the

U. S. or routed through the Mediterranean

to the Pacific. (When V-E Day arrived, 89

ships were halted at sea or recalled from

foreign ports without discharging cargo.)

If it seems incongruous that swiftly mov-

ing airpower must be anchored to the slow-

moving convoys, this is so because of the

great variety of things needed to keep an

air unit in operation. Some of these items

cannot be transported by air in sufficient

quantities.

President Truman revealed recently that

20 bombardment

groups had received orders to move from

Europe to the Far East. This number of

Flying Fortress and Liberator groups adds

up to 960 bombers, plus spares. These will

be flown to the Pacific areas, carrying with

them combat crews and some 650 tons of

immediately needed equipment. The air

echelon required to keep 'em flying after

these bombers arrive includes 4,440 spe-

clalists and technicians, and the task of re-

deploying these men demands the use of 960

Skytrain or Commando transport planes—

a fleet of planes that would take about four

hours to pass over any given point.

But this is the easiest part of the rede-

ployment. The relatively simple expedient of

transporting the planes, men and matériel

by air presents none of the difficulties fac-

ing those who must prepare for the move-

ment of the remaining personnel and equip-

ment of the 20 bomber outfits. On the

ground are left some 22,000 men and 15,800

tons of miscellaneous ground equipment that

includes everything trom bulldozers and 2%-

ton trucks to hardware such as socket

wrenches and nuts and bolts.

Railroad transportation of this comple-

ment to the nearest port will require 2,140

flat cars, 520 boxcars, 484 coaches, and 200

Kitchen and baggage cars. To embark these

men and matériel, 10 Liberty ships and nine

Army transports will be needed. Not taken

into account is the stockpile of food and

other essentials these men will consume dur-

ing the 14,000-mile voyage to some Pacific

point such as Manila.

The moving of fighter outfits will be a

slower and more complex operation. It is

not practical to ferry even the long-range

Mustangs, Thunderbolts, Lightnings, and

Black Widows over such distances. These

fighters will be shipped, along with their

combat crews, service personnel, and essen-

tial equipment.

Comparatively few fighters will be sent

from Europe to the Pacific. Only the latest

modifications, and those in the best condi-

tion, are to be redeployed. Others will be

returned to the U. S. for limited use; still

others are being scrapped for salvage. One

officer of the Air Technical Service Com-

mand, whose job it is to supply the combat

units, said, “Tt would save a lot of time,

trouble, and expense to burn on the spot

every small airplane that we won't use

against the Japs!”

Fighters that will be used are being fer-

ried from their unit bases to ATSC “proc-

essing centers” which are modeled along the

lines of the Port Newark and Oakland Over-

seas Command bases, through which passes

the flow of new aircraft to the Pacific com-

bat theaters. These centers in Europe will

be as painstaking in their work as the huge

installations here at home; there can be no

short cuts in this phase of redeployment.

We cannot afford to ship a fighter from 10,-

000 to 14,000 miles and have it arrive unfit

for immediate use.

If we consider the redeployment of, say,

ten fighter groups, each comprising some

75 planes and 1,000 men, plus spares and

equipment, it adds up to a fair-sized convoy

in itself. Thirty-three Liberties and tankers

will be required to hold the planes and some

packed parts; five Victory ships and five

transports will be needed to move the men

and the heavier equipment. More than twice

the shipping used to move 20 heavy-bomber

groups is necessary to move only ten fighter

groups and their planes.

The men from the European theater who

will fly these planes are being given short

indoctrination courses to acquaint them with

the new planes and the operating conditions

they will encounter in the Pacific. For the

most part, these differences involve more

over-water flying, more low-altitude flying

in all operations including strategic bomb-

ing, and the increased use of rockets. Pilots

who flew Marauder medium bombers in

Europe are undergoing a three-months tran-

sitional course in A-26 Invaders; so are some

of the men who flew Mitchells. Only the

latest B-25 modifications are being sent to

the Far East, and these carry rockets.

“If those Nips,” declared a procurement

officer sagely, “had any idea today how big

this thing really is and what we're getting

ready to throw at them tomorrow, they'd

have surrendered yesterday!”

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

James L. H. Peck (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1945-08

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

78-81,194,198

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 147, n. 2, 1945

Popular Science Monthly, v. 147, n. 2, 1945