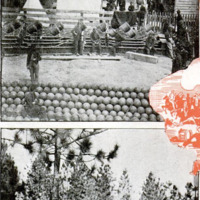

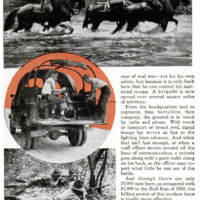

FLAGS fiying. Bugles blowing, Bewhiskered generals on white chargers waving swords, urging their men on in close-packed ranks against gray-clad warriors massed on the hill. Congressmen riding out from Washington in horse-drawn buggies to see the spectacle. That was Bull Run of the Civil War. Battle, then, was a spectacle. Comes the third battle of Bull Run, in 1939, and' Americans are once more pitted against Americans, in our greatest peacetime maneuvers. Sixteen thousand national guardsmen and reservists are out here to smash the attack of a streamline division of regulars, but there is little to see. A khaki-clad figure advances cautiously down the edge of a country road, rifle at the ready. Behind him on the other side of the road comes another soldier. Then a third and fourth, all widely spaced. From a clump of bushes up the hillside a machine gun stutters, and the point of the advance guard disappears, firing tentative1y from cover at the unseen gun. The din increases as invisible artillery opens a shattering fire from somewhere a mile off the road. A pair of observation planes drones overhead. There is a rumble and clanking from bushes off to the flank, and half a dozen tanks lumber past toward the nearest machine gun, which breaks into insane chatter, then suddenly stills. And that is all, though this is the main attack. As a spectacle, our modern battle is a complete washout. Flags cannot fly; they would draw fire. The general cannot lead a charge; a charge today is a sneaking and dashing from cover to cover by small groups of men, widely separated to offer poor targets. So the general stays back in his tent, which would be a dugout in case of real war - not for his own safety, but because it is only. Back here that he can control his scattered troops. A brigade is now spread over several square miles of territory. From the headquarters tent to regiment, then battalion, then company, the general is in touch by radio and phone. With truck or handcart or breast reel, signal troops lay wires as fast as the fighting lines advance. And when that isn’t fast enough, or when a staff officer moves around off the lines of communication, a private goes along with a pack radio slung on his back, so the officer may report what little he can see of the battle. And though there are only 20,000 men here, as compared with 67,000 in the Bull Run of 1862, the killing power of this modern force is vastly more effective. When the Civil War opened, the entire federal army possessed only eight batteries of artillery, totaling but forty-eight pieces. Half of these were three-inch muzzle loading rifles having a range of 2,800 yards. The other half were twelve-pound smooth-bore Napoleons, with a range of 1,520 yards. But beyond 600 yards the effect of the smoothbores was very uncertain. The velocity was so low at long ranges that alert soldiers could and did dodge the shot, which came at them only twice as fast as would a hard-hit baseball. Working at top speed, these old muzzle loaders could be fired about once a minute - for short periods. In the 1939 maneuvers, the smaller forces employed were armed with 120 seventy-five-millimeter guns, having a range of 12,800 yards and the ability to hurl twenty-five shots a minute—with extreme accuracy. Then there were thirty-six 155-millimeter howitzers with a range of 15,400 yards, firing two ‘shb{s aminute with ease; and twenty-four anti-airtraft guns. Infantry troops employed twenty Stokes-Brandt mortars, each capable of hurling thirty eighty-one-millimeter high-angle shells a minute at a maximum range of 3,300 yards; and twenty thirty-seven-millimeter guns, carried on light hand-drawn carts. These little guns, extremely effective against tanks and machine-gun emplacements, have a range of 4,500 yards, and can be fired thirty-five times a minute. That's a total of nearly 5000 explosive shells a minute, as against possible forty-eight at the first Bull Run. The Civil War troops carried about 50,000 muzzle-loading, single-shot rifles, deadly at 500 yards, and with an extreme range about double that. Highly trained troops could reload and fire such arms twelve times a minute, but most of the soldiers at the first Bull Run were the rawest of recruits. Four aimed-shots a minute would be an extremely generous allowance for them. First army troops at the 1939 maneuvers carried 9,044 Springfield rifles, with which ten aimed-shots a minute can be fired with ease. This rifle has an extreme range of 5,500 yards, though few men can see well enough to hit anything with a rifle at more than 1,200 yards. Then there were 1,120 automatic rifles capable of discharging 150 rounds a minute, and 559 machine guns firing 600 shots a minute - a total of nearly 700,000 rounds every sixty seconds, rounds which kill at much greater distances. Many of the machine guns were carried in the seventy-six light tanks, hence could advance unharmed against rifle and machine-gun fire, This tremendous power of modern weapons to kill is what makes today’s battlefield apparently devoid of life. The whine of machine-gun bullets, the nerve-shattering crash of high explosive, have so driven the present-day soldier to cover that his opponent catches only fleeting glimpses of him. Only fragmentary bits of battle flash before the observer. The greatest contrast between the battles of 1862 and 1939 was the matter of mobility. It took General McDowell two full days to march his federal army from Washington to Centerville, only twenty miles away. Two hours was all the motorized regular division needed to move that distance in the 1939 maneuvers. One fact revealed by the Bull Run of 1939 is that the regular army, which is supposed to be ready for action on the day of mobilization, is not ready now. Its ranks are below peace strength, less than half of war strength. It is deficient in all types of modern weapons. The National Guard suffers from these same defects but in a much greater degree. Though mobilization plans call for the guard to take the field thirty days after mobilization, General Drum, commanding the first army, estimates that from six months to a year of intensive training would be needed before the units are ready for battle.