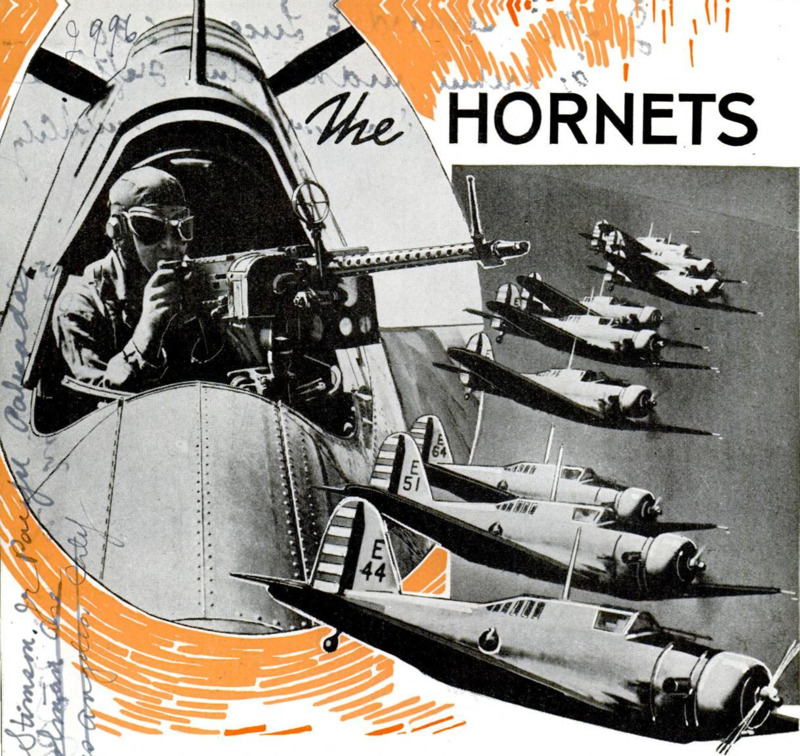

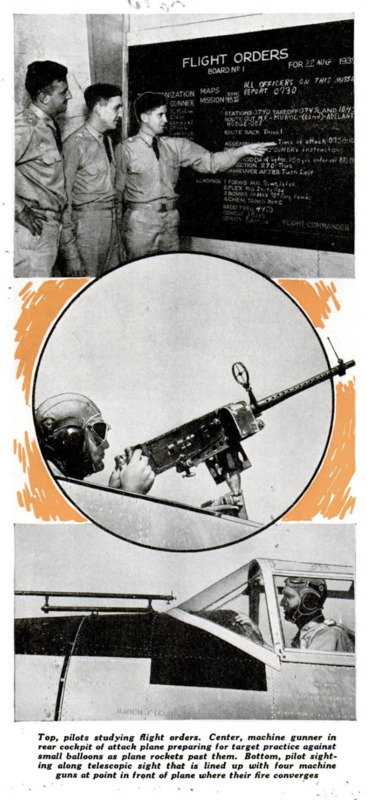

The Hornets of the Air Corps

Item

- Title (Dublin Core)

- The Hornets of the Air Corps

- Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

- The Hornets of the Air Corps

- Language (Dublin Core)

- eng

- Temporal Coverage (Dublin Core)

- World War II

- Date Issued (Dublin Core)

- 1940-03

- Is Part Of (Dublin Core)

-

Popular Mechanics, v. 73, n. 3, 1940

Popular Mechanics, v. 73, n. 3, 1940

- pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

- 386-389, 126A

- Rights (Dublin Core)

- Public Domain (Google digitized)

- Source (Dublin Core)

- Google books

- References (Dublin Core)

- Northrop A-17

- March Air Reserve Base

- California

- Arizona

- Native American tribe

- United States Army Air Corps

- Archived by (Dublin Core)

- Enrico Saonara

- Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

- Spatial Coverage (Dublin Core)

- United States of America