-

Titolo

-

Army on Wheels, part I

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Army on Wheels, part I

-

extracted text

-

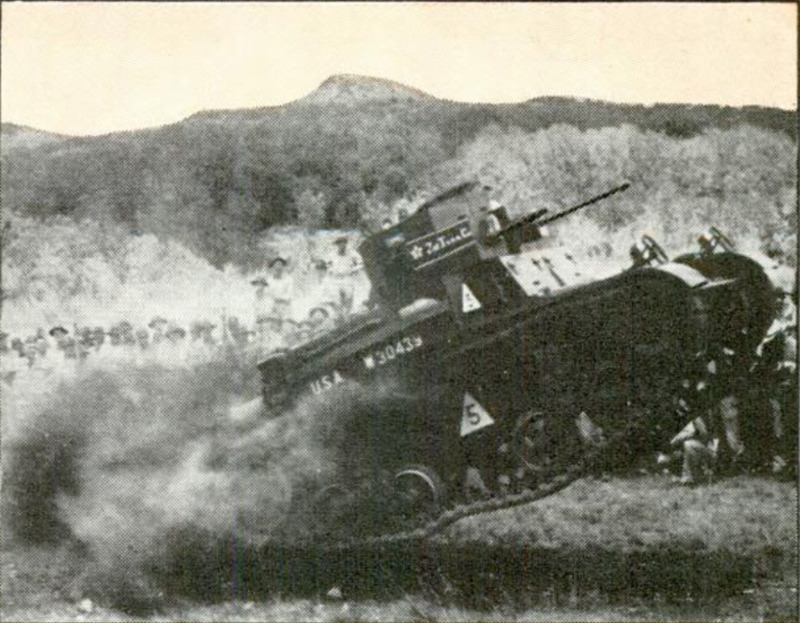

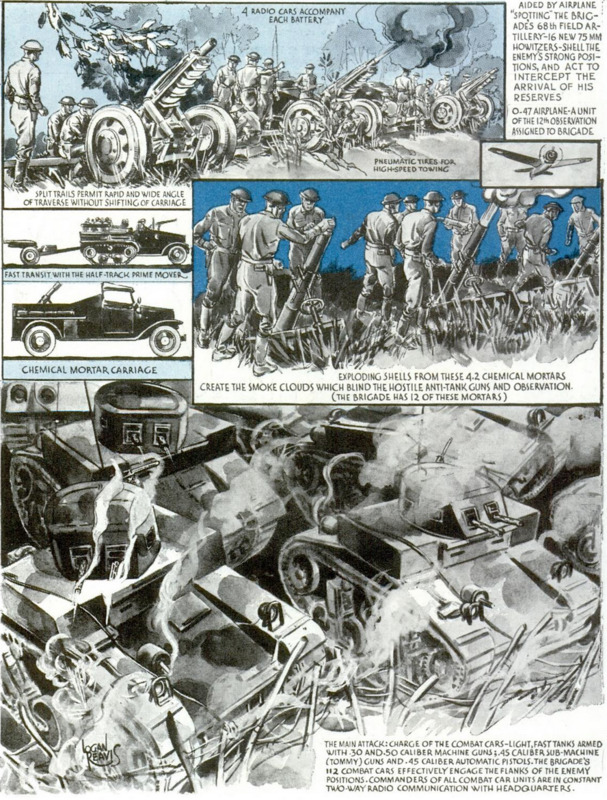

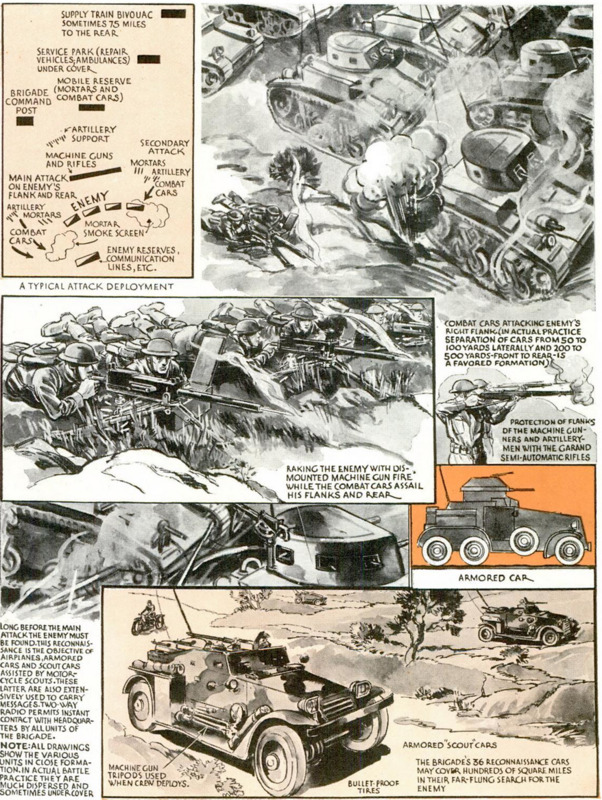

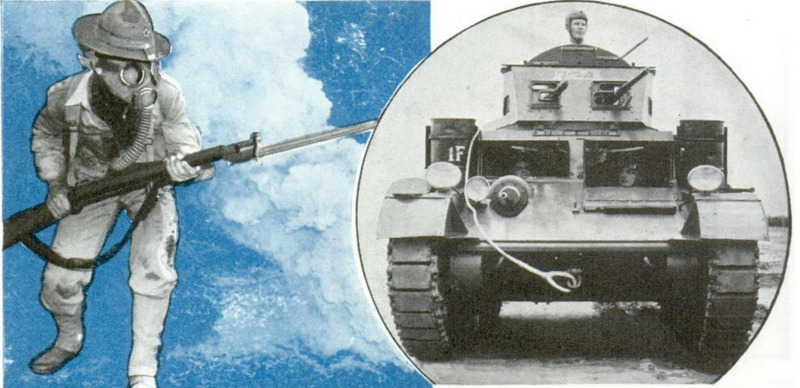

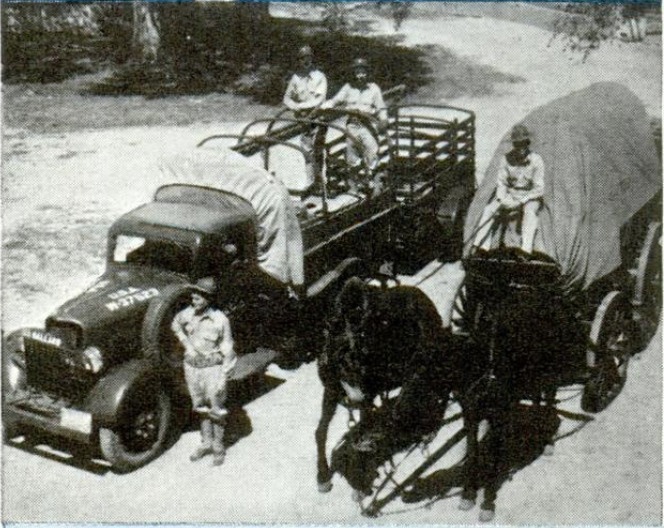

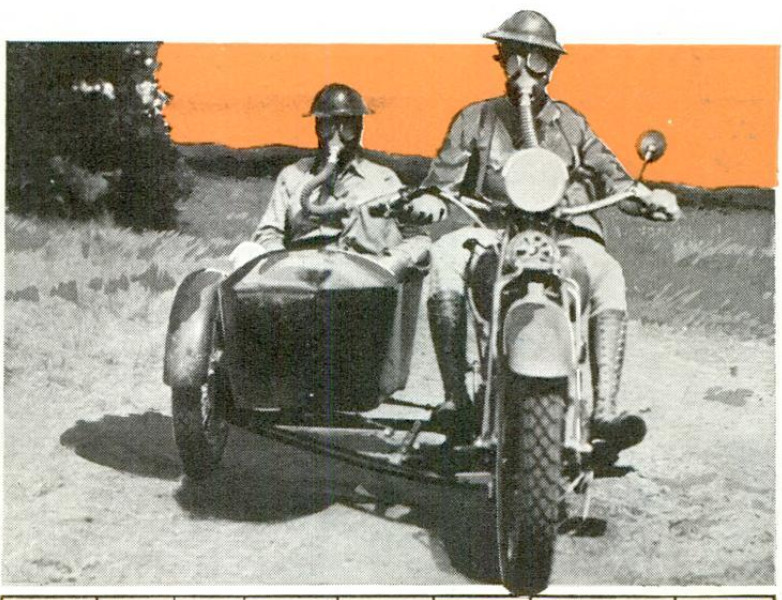

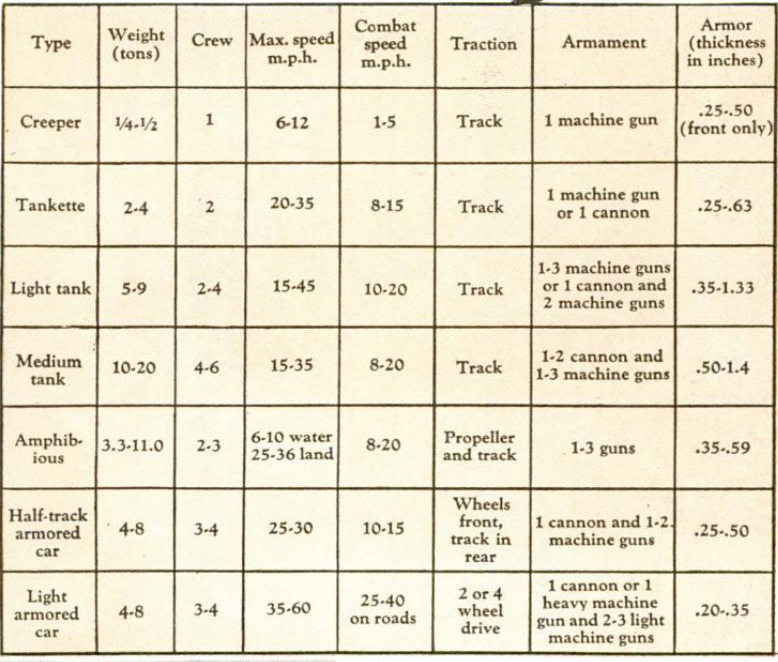

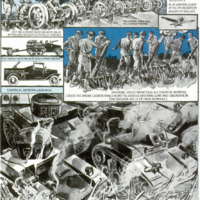

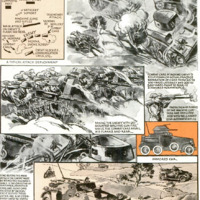

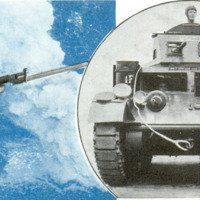

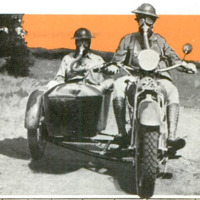

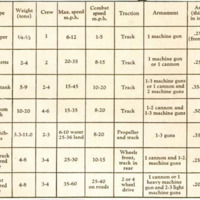

TANKS on the ground, plants in the sky, pig boats under water; radio direction finders, mechanical fire-control computers, automatic rifles - it's a machine age in war as in peace. Many of us are inclined to make the rash conclusion that war today is entirely an affair of machines - with robots taking the place of flesh and blood. Nothing could be farther from the truth. War is waged by men; men drive machines. Mars is simply utilizing the latest in mechanical developments as he has since the first caveman found that by rushing on his opponent, stick or stone in hand, he could do better than by walking slowly at him, barehanded. That first caveman didn’t know it but he was utilizing the basic elements of mechanics - force and motion. Ever since that time men have taken advantage of mechanical contrivances on land and sea. Invention of the wheel was the first step toward the earliest form of tank, the chariot. The sling, the bow, the arbalest, the ballistae hurling great rocks, later gunpowder, ushering in firearms - all of these things are machines, some invented for use in war, others adapted to it from pacific uses. And for each new invention in offensive, each improvement in the art of war, man in turn invented something to defend himself against it, from the shield of hide to the armor plate, from the simple shelter of a tree or hummock to the Maginot line and the Westwall. Fire and movement, striking power and mobility are the aids mankind has been seeking since that first caveman’s rock-implemented rush. The two things are diametrically opposed. The Roman short sword stopped the Greek phalanx, the British longbow the armored knights of France. The machine gun’s stutter sounded the knell of cavalry's earth shaking charge. Armor and armor-piercing projectiles have vied with one another since before the invention of steel. And now the perfection of the motor vehicle has brought into being the mechanized forces - troops that fight from moving vehicles, differing from the hide-armored, scythe-armed, arrow-shooting chariots of ancient history only in degree of human invention. The fight between fire power and mobility has alwavs brought about a compromise, for the faster the movement, the less protection can be carried. Conversely, the heavier the protection, the more massive the weapon, the less the speed. In our own Civil War railroads were prime factors for mobility too in the Austro-Prussian war of 1866. By the time of the World War, fire power - the long range punch of artillery, the deadly hail of the machine-gun bullet - combined to halt mobility. Then came the tank, as compromise, for it combined to a certain degree mobility and fire power or striking power. Today an improved tank, with increased mobility as well as increased fire power, is in the field. And already its Nemesis has appeared - the anti-tank gun. Last September, Poland was eliminated as a combatant because the German invasion disrupted the entire economic structure of the nation; destruction of Polish armed forces was of secondary importance and a logical conclusion once the industrial heart of the nation was penetrated. This was accomplished by use of mechanized forces which, being mobile, dashed ahead at top speed, and, having fire power or punch, brushed aside local resistance. Foot troops, infantry, able to hold the terrain dominated by the mechanized thrust, followed fast. And foot troops, armed men on the ground, are the decisive factors in war. Perhaps the most brief, the most illuminative word-painting of what this all means is the homely language of General Nathan Bedford Forrest, of the Confederate Army, who expressed all the principles of war in this remark - “Git thar fustest with the mostest men.” This can be done in two ways - by using transportation to get troops onto the field of battle, when they must then dismount and fight on the ground, or by using the vehicles not only for transport, but as actual fighting platforms. Today we call the first motorization the second mechanization. The words do not mean the same thing. The basis for mechanization is of course the cross-country vehicle, which by one of several ingenious devices, most of them adaptations of the so-called Caterpillar tread, or endless-chain track, can cover ground which an ordinary wheeled vehicle cannot cross. Mechanization began with the World War tank, a cumbersome armored tractor which lumbered across country at the pace of walking infantrymen, protecting them in its advance, crushing machine-gun nests, knocking down barriers, crossing ditches and trenches. Today tanks, both light and medium, which can in theory make forty miles an hour or more, are still the basic vehicles of mechanized forces. We say “in theory” because in fact a vehicle of this type crossing rough terrain is limited more by the human element than by its traction. One must remember that in action the driver, completely enclosed, has most limited vision. How fast would you drive your auto, on the road, if your only observation was through narrow eyeslits? Multiply this by the obstacle-dodging necessity of cross-country driving, and you will realize that only under most exceptional circumstances, on smooth ground, could extreme speed be kept up. The heavy tank or “land battleship,” is a special weapon for special circumstances, such as a break-through on a stabilized front, and has been discarded by some nations. Armor used on tanks covers only the vital parts, and is not all-round, hence tanks are more vulnerable on top and bottom. Again we see the conflict between the two opposed factors of mobility and fire power. It might be possible to build a tank which would be impervious to anything but heavy artillery projectiles; when you do this, however, you instantly slow up its speed out of all proportion. A nearly motionless tank cannot carry out its mission. Light, medium and heavy tanks have two uses - accompanying, that is, moving with their infantry and assisting its forward movement; and leading, that is, to charge and clear the way for infantry. Tanks have certain basic limitations: their noise, which can be heard a mile or more away, and which, inside the vehicle is terrific, limiting communications and preventing the crew from locating anti-tank guns by ear; poor vision of crews; distinctive appearance; ineffectiveness of their fire at any but the most limited ranges, because of poor vision and eccentricity of motion; limitations of ammunition supply; terrific strain on the crews, and sensitivity to terrain. Deep mud and sand, and stump land are serious obstacles. Steep-sided ditches, felled trees, pits – like elephant traps - in roads and artificial obstacles like concrete pyramids, will break up tank attacks. Most tanks can cross ditches five to six and one-half feet in width and can ford streams up to three feet in depth if the bottom be firm. Mines, portable affairs ‘which weigh about five pounds, detonated by contact, can be sown in fields which might be perfect avenues of approach. Heavy woods are tank obstacles, but sparse woods may work to their advantage as tanks can push over trees up to six inches in diameter, and scattered trees may provide cover for them to creep up within charging distance. But of all anti-tank weapons artillery is the most to be feared. To understand this we must visualize the penetrative power of projectiles in armor plate. The figures given above are based on a direct hit with ninety-degree angle of incidence, that is, with the bullet meeting the armor plate squarely. However, one must remember that absolute destruction of the tank is not the essential object of anti-tank fire. The shot that knocks off a tread or otherwise cripples the progression of the vehicle is sufficient. To assume that the tank is not a dangerous weapon, however, is erroneous. The tank is a highly dangerous and highly important weapon, since it provides for the attacker an increase of mobility and an additional striking power crushing through defensive works which would otherwise hold up the infantry. It is an essential member of the combat team. Insofar as the infantry are concerned, the tank, used either as an accompanying weapon or as the spearhead of an attack, must be considered by both attack and defense. Its use as either or both depends upon national doctrine, terrain and tactical situation. Some countries, for instance Germany and Russia, contend that the hammer-blow, in advance of the infantry, is the true role of the tank. Others, among them France, hold that tanks should move side by side with the foot troops.

-

Autore secondario

-

R. Ernest Dupuy (writer)

-

U.S. Army Signal Corps (photos)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1940-01

-

pagine

-

1-5, 146A, 148A-149A

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Enrico Saonara

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)