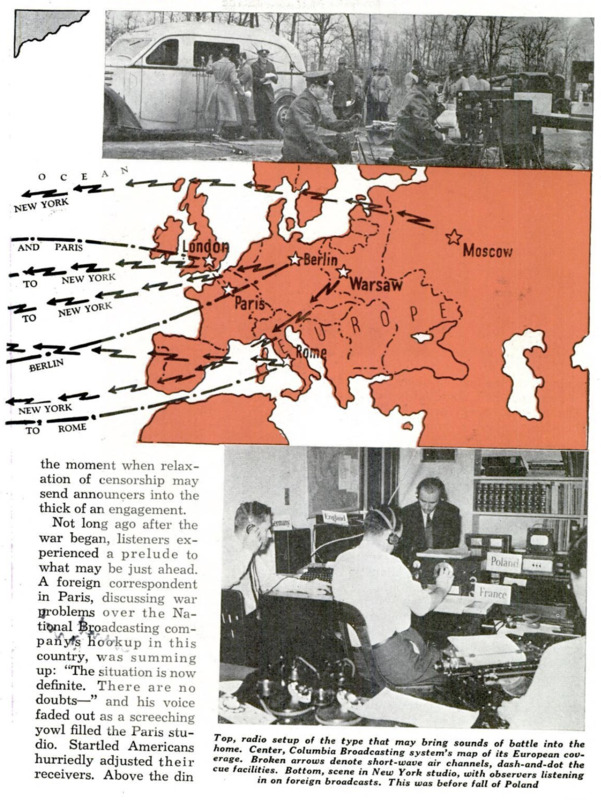

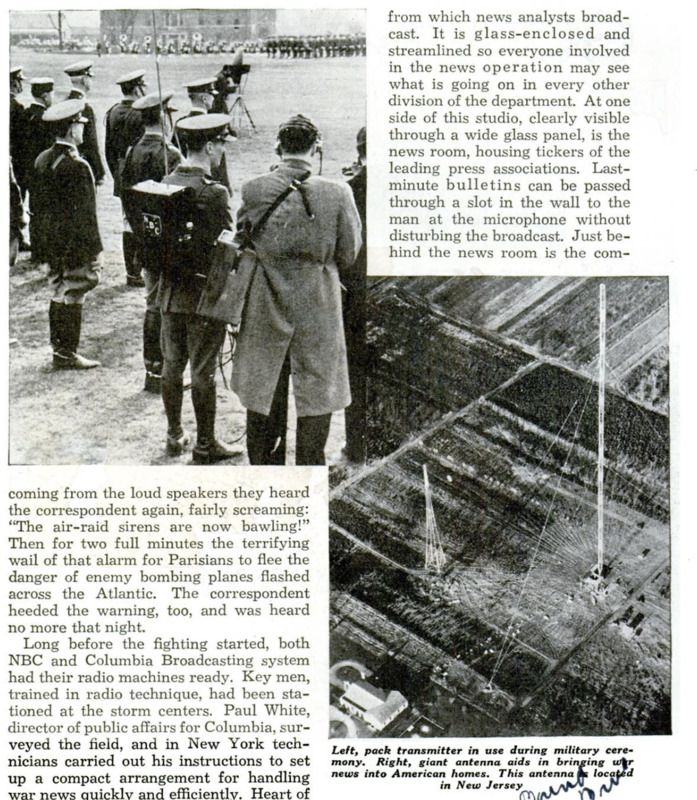

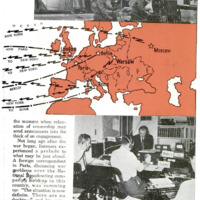

THROUGH the medium of radio, Americans are being taken into the theater of Europe’s war. Directly from the capitals of the nations involved come the voices of trained observers, each describing last-minute developments on his part of that farflung stage of strife, and it is possible that your loud speaker soon may be roaring with the din of battle. Portable transmitters, tested in sham battles here and abroad, offer the means of broadcasting to a shuddering world the rattle of machine guns, the shriek of shells from booming big guns and the thunder of monster tanks, with the high-pitched whine of fighting planes superimposed on the whole ear-splitting drama. Already the British Broadcasting company has moved transmitters and other equipment on wheels to the front in preparation for the moment when relaxation of censorship may send announcers into the thick of an engagement. Not long ago after the war began, listeners experienced a prelude to what may be just ahead. A foreign correspondent in Paris, discussing war problems over the National broadcasting companys hookup in this country, was summing up: “The situation is now definite, There are no doubts - " and his voice faded out as a screeching yowl filled the Paris studio. Startled Americans hurriedly adjusted their receivers. Above the din coming from the loud speakers they heard the correspondent again, fairly screaming: “The air-raid sirens are now bawling!” Then for two full minutes the terrifying wail of that alarm for Parisians to flee the danger of enemy bombing planes flashed across the Atlantic. The correspondent heeded the warning, too, and was heard no more that night. Long before the fighting started, both NBC and Columbia Broadcasting system had their radio machines ready. Key men, trained in radio technique, had been stationed at the storm centers. Paul White, director of public affairs for Columbia, surveyed the field, and in New York technicians carried out his instructions to set up a compact arrangement for handling war news quickly and efficiently. Heart of the setup, on the seventeenth floor of the system’s building, is White’s office, in which an amazing battery of wires, telephones and dictagraphs permits him to cut into the network with a war bulletin in five seconds - no small achievement when you remember that there are as many as 117 stations in the hookup. Across from this office is “Studio Nine,” from which news analysts broadcast. It is glass-enclosed and streamlined so everyone involved in the news operation may see what is going on in every other division of the department. At one side of this studio, clearly visible through a wide glass panel, is the news room, housing tickers of the leading press associations. Last-minute bulletins can be passed through a slot in the wall to the man at the microphone without disturbing the broadcast. Just behind the news room is the communications division where contact is maintained with all stations of the network at all times, and on the other side of Studio Nine is the listening station where foreign language experts listen in on European | broadeasts as an extra check on picking up news tips and following developments as they are portrayed by government radios abroad. To the rear of Studio Nine is a specially constructed control room known as the sub-master control room. In times of crisis the entire operation of the network passes through this room so that an important bulletin may be put on the air with minimum delay. NBC likewise was ready, staff and technical facilities being keyed up far in advance of both the crisis and the war, to flash the latest news through the 176 stations in its Red and Blue networks. Stationed at various points in Europe were observers and news directors. From London, Paris, Berlin, Rome and Geneva broadcasts traveled directly by transatlantic short-wave channels to RCA Communications, the receiving point at Riverhead, Long Island. Thence they were transmitted by wire to a master control room in Radio City, located in New York, and finally by wire lines to stations scheduled to receive the broadcasts. From these local stations the news was transmitted on regular wave-lengths to listeners. Broadcasts from other foreign cities, such as Warsaw before its fall, which do not always have dependable direct transatlantic short-wave facilities, were sometimes wired to Geneva, Paris or London and then short-waved across the ocean to diversity receiving units at Riverhead. A diversity unit comprises three receivers, each of which is equipped with an automatic gain control. The strongest of the three receivers automatically feeds the line amplifier, the output of which goes by wire to the master control room. Thus, if one of the signals becomes too weak for dependable U. S. reception, another receiver goes into action automatically. Most of the foreign talks are arranged well in advance of the actual broadcast. Should a commentator have something important, he radiograms the special events department, which is directed by A. A. Schecter, telling when he wants to go on the air, and transatlantic and local channels are cleared for him. During the days just preceding the war, NBC’s special events department was a chaos of wires, microphones and technical equipment. Events moved so fast that a miniature master control room, with monitoring facilities and all, was established there in order to expedite broadcasts. A twenty-four hour day was in effect for most of the personnel; sandwiches and coffee comprised the diet of most of the staff for a full week, with the result that in the ten days preceding outbreak of hostilities more than 150 foreign broadcasts were brought to American listeners by NBC. Technically the war has been marked by Columbia’s use of a four-way hookup, which renders possible conversations on the same program between experts in New York, Washington, Paris and London. When CBS technicians tackled the problem of giving American listeners a balanced picture, in one program, of the situation as it developed in world capitals, a four-way conversation required the use of several short-wave channels and cue channels. To eliminate the multiplicity of channels, the staff developed a complicated arrangement of circuits and amplifiers whereby each man on the program could hear the voices of every other man, but not his own. If his own voice had been audible, the slight time lag would have destroyed the clarity of the program. But more important, it was possible to carry the entire program on two channels, one eastbound and one westbound. Dress rehearsals for the European coverage had been held by the broadcasting companies in the form of broadcasts of U.S. Army maneuvers, In these sham battles, one announcer carries a pack transmitter, weighing perhaps twenty-five pounds, on his back and does most of the talking. Behind him, in a mobile unit, is an engineer and a few miles away, in a tower, are stationed a few observers commanding a view of much of the “battle” front. Their position compares with that of an observation balloon in a real engagement. Other staff men, many of them Reserve Corps officers, are stationed at various strategic points - at General Headquarters, in observation planes, around the battlefield - while others perform the duties of liaison men. The announcer, with his one or two-watt pack set, transmits signals, while the “battle” rages, to the mobile unit, which is equipped with a transmitter, of perhaps twenty-five-watts power. From there the signals are retransmitted to a seventy-foot tower far back of the lines and operated around 2,000 kilocycles. The signal then is picked up by a receiving station located at General Headquarters and retransmitted once more to a central control station, thence by special telephone circuit to the master control room where it is fed to the networks. By using several wave lengths the engineers are able to avoid concentration of interference on any one channel by the hundreds of transmitters being used by the opposing “armies.” Broadcasts of army maneuvers have demonstrated that radio coverage of a single engagement between Germany and the Allies might run into countless thousands of dollars. In the first place the best of short-wave and ultra-high frequency transmission paraphernalia must be put into action. Second, a battle cannot be counted on to occur within the vicinity of the mobile transmitters, and third, a miniature radio army must be used for speedy and efficient coverage. But in the face of tremendous expense and untold mechanical difficulties, the broadcasting companies are ready to undertake battlefield broadcasts. If and when the censorship is lifted by the warring powers, you'll be able to tune in the voice of the big guns.

Popular Mechanics, v. 73, n. 2, 1940

Popular Mechanics, v. 73, n. 2, 1940