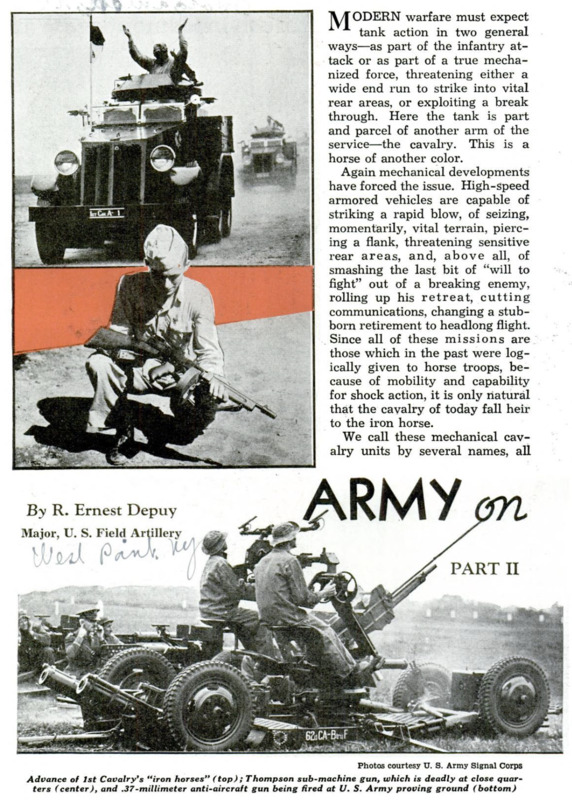

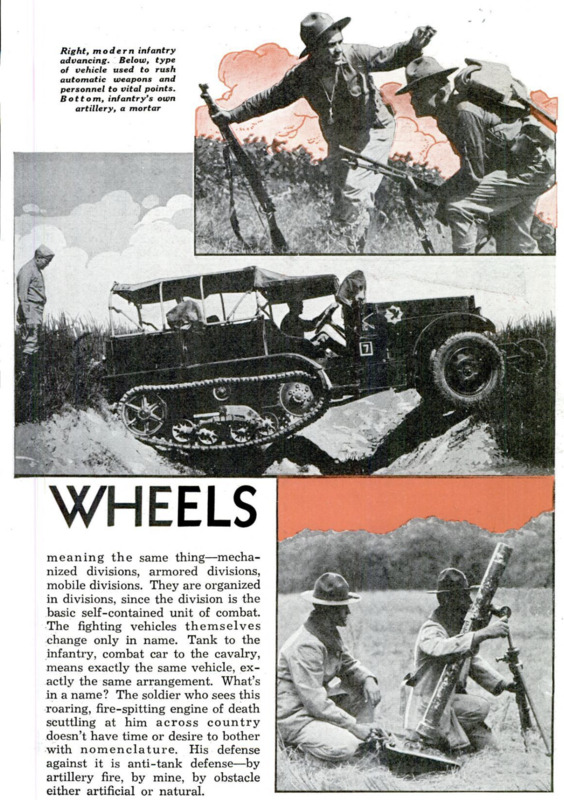

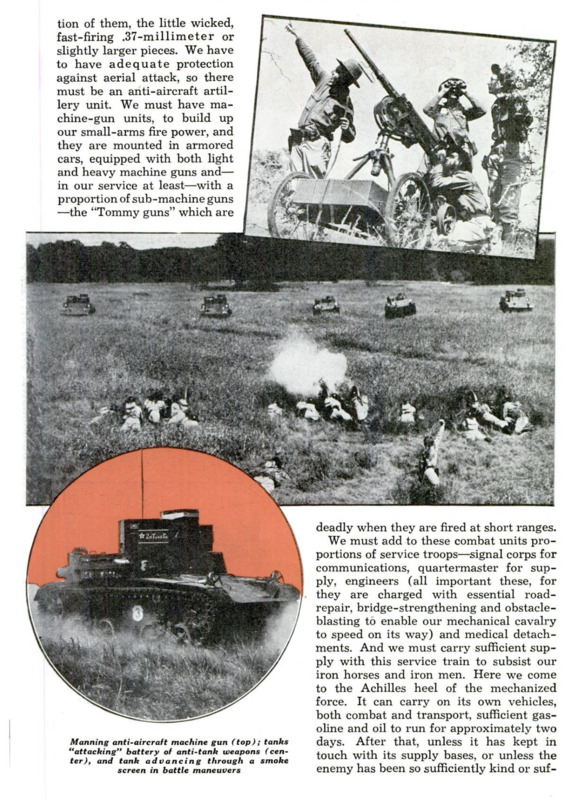

MODERN warfare must expect tank action in two general ways - as part of the infantry attack or as part of a true mechanized force, threatening either a wide end run to strike into vital rear areas, or exploiting a break through. Here the tank is part and parcel of another arm of the service - the cavalry. This is a horse of another color. Again mechanical developments have forced the issue. High-speed armored vehicles are capable of striking a rapid blow, of seizing, momentarily, vital terrain, piereing a flank, threatening sensitive rear areas, and, above all, of smashing the last bit of “will to fight” out of a breaking enemy, rolling up his retreat, cutting communications, changing a stubborn retirement to headlong flight. Since all of these missions are those which in the past were logically given to horse troops, because of mobility and capability for shock action, it is only natural that the cavalry of today fall heir to the iron horse. We call these mechanical cavalry units by several names, all meaning the same thing - mechanized divisions, armored divisions, mobile divisions. They are organized in divisions, since the division is the basic self-contained unit of combat. The fighting vehicles themselves change only in name. Tank to the infantry, combat car to the cavalry, means exactly the same vehicle, exactly the same arrangement. What's in a name? The soldier who sees this roaring, fire-spitting engine of death scuttling at him across country doesn’t have time or desire to bother with nomenclature. His defense against it is anti-tank defense – by artillery fire, by mine, by obstacle cither artificial or natural. To date, since the mechanized division is a new weapon, we find its composition differing in the armies of the various nations, most of whom admit that they are frankly experimenting with the proportions of the various types of weapons, and vehicles, and the man power in such units. The best one can do is enumerate the various pieces of armament which are essential - the proportions may change. Primarily we have tanks - light and medium - the striking power. Next we must have lighter and faster vehicles which can carry on reconnaissance for miles ahead, which can protect the flanks, and in general do for our land battleships what the leaping destroyers and light cruisers do for the battle fleet. These we call armored cars. They have slight protection to cover their occupants from small-arms fire, and carry machine guns with which to fight. But since one of the missions of the mechanized division may be to dash out, seize and hold ground somewhere, we must take foot troops along.So, we | take them mounted on trucks, in place of the mounted infantry that were sometimes used in the past to gain mobility, the mounted infantrymthat became dragoons. It is interesting to note that the French today call these motorized infantry units, “dragons portees,” literally, “transported dragoons.” They, of course, cannot fight from their vehicles, and it is not intended that they should thus enter the fire fight. They come to hold ground that the tanks have seized. We need artillery, entirely aside from the light guns mounted on the tanks; we must have fire power to overcome resistance, to cover our advance, to support our infantry when they have dismounted to fight on foot. So we bring them along, motorized of course, 75-millimeter guns or howitzers - or some similar caliber. And we must have anti-tank guns to fight off enemy tank attacks, so we add a proportion of them, the little wicked, fast-firing .37-millimeter or slightly larger pieces. We have to have adequate protection against aerial attack, so there must be an anti-aircraft artillery unit. We must have machine-gun units, to build up our small-arms fire power, and they are mounted in armored cars, equipped with both light and heavy machine guns and - in our service at least - with a proportion of sub-machine guns - the “Tommy guns” which are deadly when they are fired at short ranges. We must add to these combat units proportions of service troops - signal corps for communications, quartermaster for supply, engineers (all important these, for they are charged with essential road repair, bridge strengthening and obstacle blasting to enable our mechanical cavalry to speed on its way) and medical detachments. And we must carry sufficient supply with this service train to subsist our iron horses and iron men. Here we come to the Achilles heel of the mechanized force. It can carry on its own vehicles, both combat and transport, sufficient gasoline and oil to run for approximately two days. After that, unless it has kept in touch with its supply bases, or unless the enemy has been so sufficiently kind or sufficiently frightened as to leave fuel supplies in our path, we jolt to a halt. Horses and men, animate beings with heart, can go on above and beyond their physical necessities for astounding periods. But who ever heard of a carburetor with a heart? And tanks cannot graze. Summing up, we find in the average mechanized division a unit combining fire power and mobility, with ability to cover ground at approximate1y 200 miles per day, and capable normally of moving and fighting for two days without replenishment of fuel or ammunition, across country, though with some limitations. Visualizing the bounds that this force can make, the comparative ease with which it can be shifted from flank to flank in open warfare, the terrific punch that it carries, we see that the mechanized division is a weapon of tremendous possibilities. Not least of them is the moral effect on the other fellow, for the problem of reconnaissance and security is multiplied enormously. No longer will scattered patrols be sufficient flank or rear guard within potential range of the armored force, for its striking power will carry it through them like a bullet through paper. Troops of all arms must be diverted from normal missions to protect on all sides. We come back in effect to the days of Julius Caesar, when the Roman soldier, at the end of each day’s march, actually dug himself into a fortified camp - four-square against enemy attack. Best conception of the strength contained in a typical armored division may be gained from a glance at the make-up of a German unit of this type - a so-called “Panzer” division. Its nucleus is a brigade of tanks, consisting of three regiments, each of two battalions of four troops - approximately 680 light and 170 medium tanks. It has a brigade of motorized infantry, consisting of three regiments each of three battalions of four companies, besides a machine-gun battalion of four companies, and a thirty-gun anti-tank artillery battery. One of the battalions in eachinfantry regiment is motorcycle-mounted. Its artillery consists of a battalion of twelve 105-millimeter howitzers. A reconnaissance squadron of four troops of armored cars, a signal and a pioneer battalion, and a small service train complete the unit. The division has twenty-eight light and twelve heavy armored cars. The fire power of the division, in addition to the weapons mounted on the tanks and armored cars and the 105-millimeter howitzers and anti-tank - guns, consists of 260 light and 180 heavy machine guns, to which must be added the rifle companies of the infantry brigade. The estimated man strength of such a division is approximately 11,000. And Germany today is said to have six such divisions. In our own service, true mechanization - we had tanks before, of course - started in February, 1928, with the organization of the Provisional Platoon, 1st Armored Car Troop, at Fort Myer, Va. Now our mechanized cavalry consists of the Tth Cavalry Brigade, composed of the st and 13th Cavalry and the 68th Field Artillery. Since an armored division should include, as stated above, a brigade of combat vehicles plus a brigade of motorized infantry and the necessary motorized field artillery, it will be seen that the addition of one of our motorized infantry brigades to the 7th Cavalry Brigade would fill the bill. It is a comforting thought to Americans that our youth are brought up in a motorized atmosphere; that mechanical ability is latent in them. Few and far between are the young Americans who cannot drive a motor vehicle, who cannot almost instantly grasp simple mechanical problems. Now the driving of a tank or combat car is much more difficult and complicated than tooling an automobile or truck. But the man who can do the latter is prepared to learn rapidly the minutiae of the former. The present increase in our regular army is bringing a great demand for men who can operate motor vehicles of all types, not the least being for service in the swift-moving tanks of the infantry, the combat cars and half-tracks of the cavalry, the rapidly rolling trucks that pull our field artillery along the road at high speeds. This demand is accentuated by the necessity for duplicate crews of motor veshicles. The army has found out that for long motor marches both drivers and assistant drivers must be shifted for safety’s sake as well as for necessary relief from strain. The tired assistant driver may nod to sleep just as dangerously as the tired driver, with equally fatal results. All of which brings us right back to our initial premise that although this is a mechanical age, machines are run by men, and men fight wars. Man is the director, the machine his servant.

Popular Mechanics, v. 73, n. 2, 1940

Popular Mechanics, v. 73, n. 2, 1940