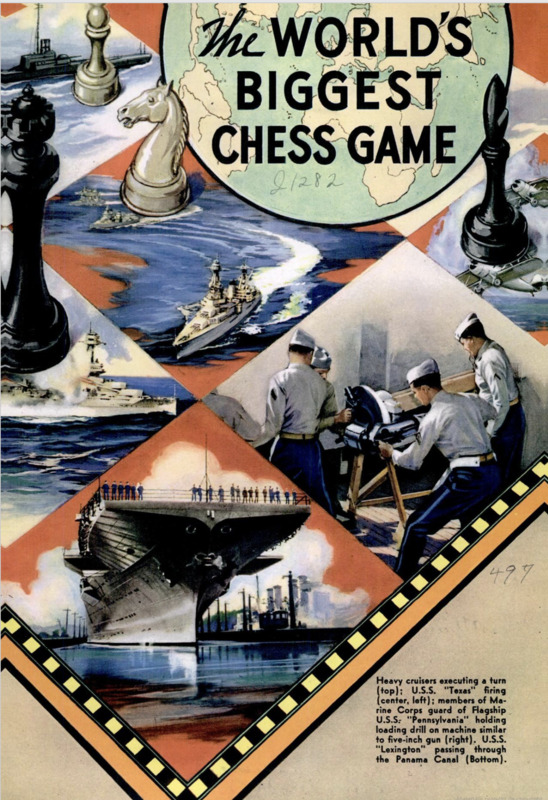

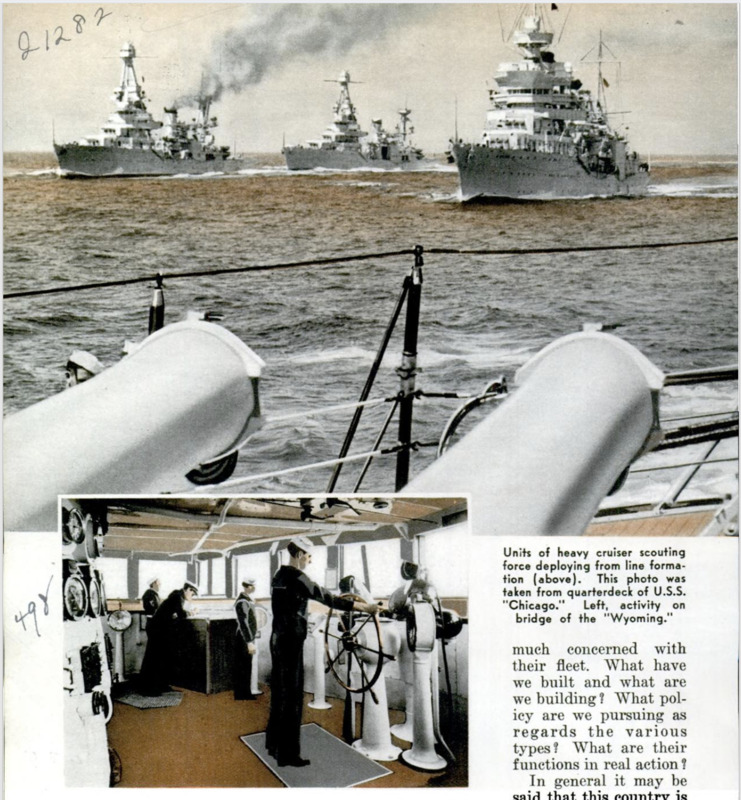

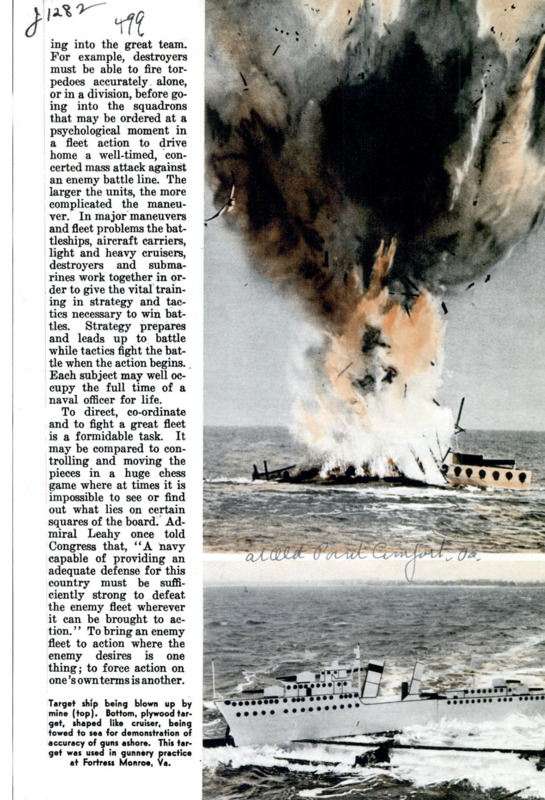

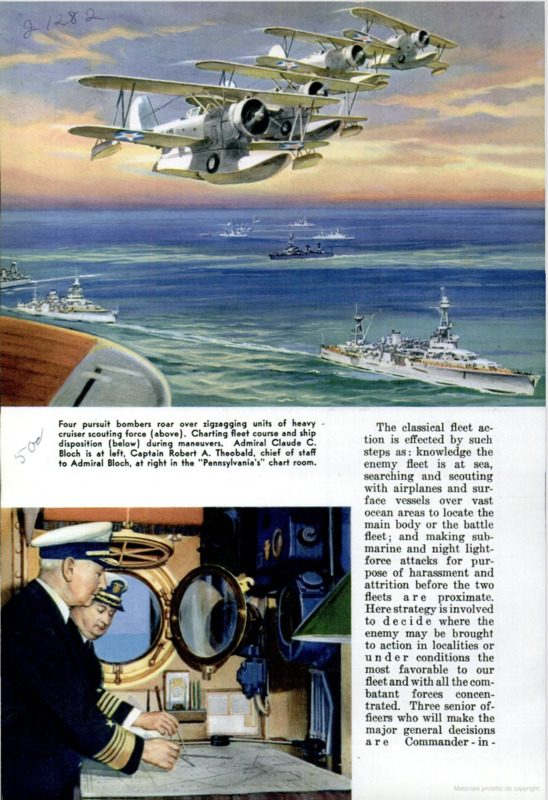

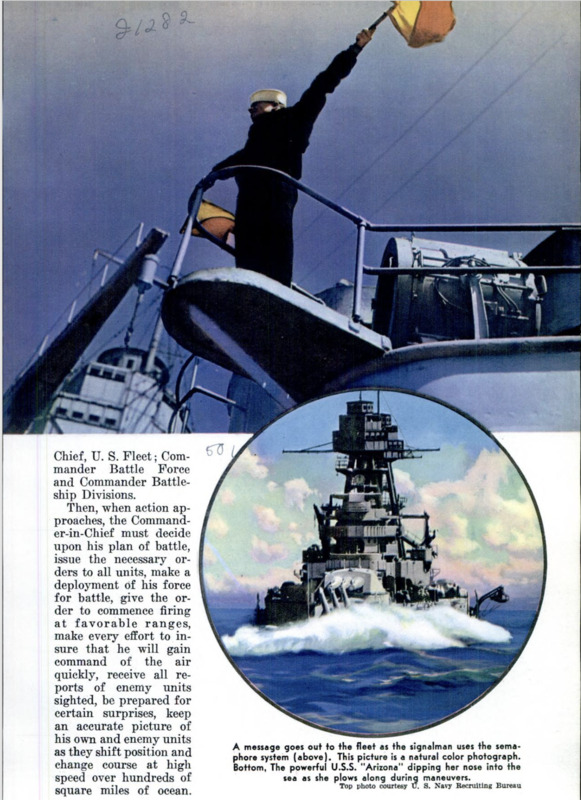

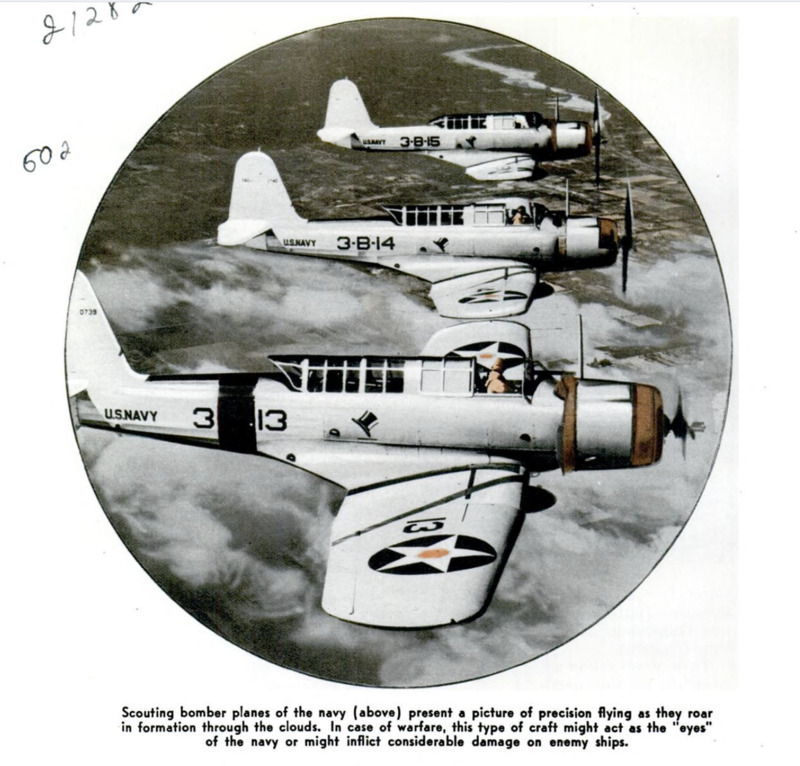

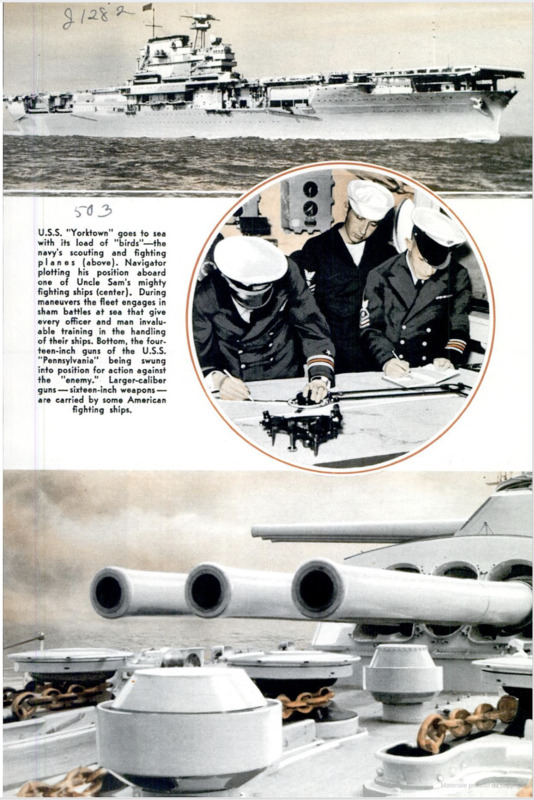

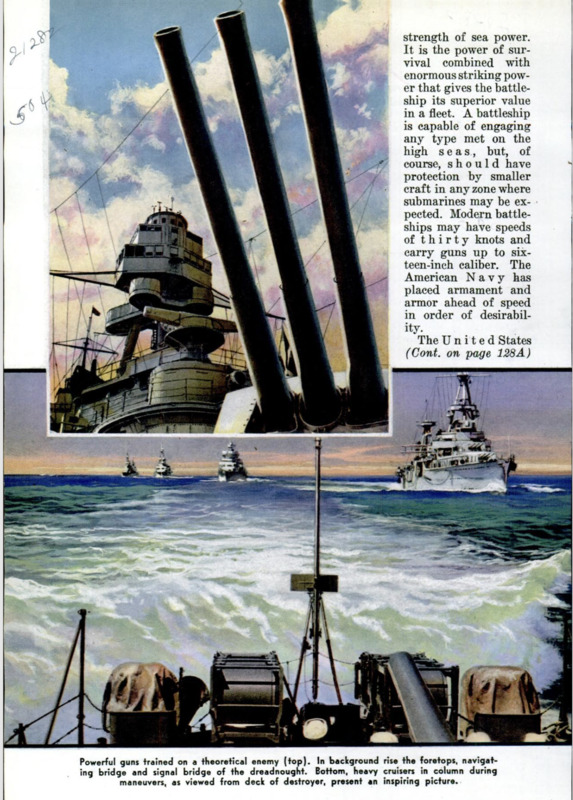

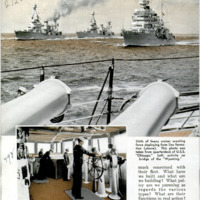

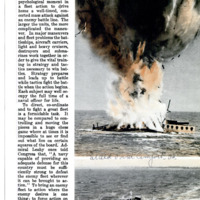

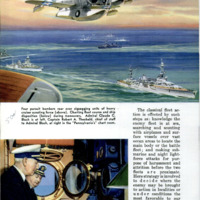

FROM the ‘‘wooden walls’’ of the Revolution and the War of 1812 to the ironelads of the Civil War, and the destroyers of the World War, the United States Navy has been an important factor in every war in which this country has been engaged. Today the navy stands as the outer bulwark of American defense. Naturally the American people are much concerned with their fleet. What have we built and what are we building? What policy are we pursuing as regards the various types? What are their functions in real action? In general it may be said that this country is building in an orderly manner a homogeneous, well-balanced fleet. Or, to put it in football language, it means a smooth offensive team, for which the successful functioning of each position or player is required for victory. We do not want too many guards (battleships), and too few backs (aircraft carriers) for unleashing the air attack. We want a balance in the tackles (cruisers) and the ends (anti-aireraft defense). Each unit in each type must be trained to fulfill its mission as a type before going into the great team. For example, destroyers must be able to fire torpedoes accurately. alone, or in a division, before going into the squadrons that may be ordered at a psychological moment in a fleet action to drive home a well-timed, concerted mass attack against an enemy battle line. The larger the units, the more complicated the maneuver. In major maneuvers and fleet problems the battleships, aircraft carriers, light and heavy cruisers, destroyers and submarines work together in order to give the vital training in strategy and tactics necessary to win battles. Strategy prepares and leads up to battle while tactics fight the battle when the action begins. Each subject may well occupy the full time of a naval officer for life. To direct, co-ordinate and to fight a great fleet is a formidable task. It may be compared to controlling and moving the pieces in a huge chess game where at times it is impossible to see or find out what lies on certain squares of the board. Admiral Leahy once told Congress that, “A navy capable of providing an adequate defense for this country must be suffciently strong to defeat the enemy fleet wherever it can be brought to action.” To bring an enemy fleet to action where the enemy desires is one thing; to force action on one’s’own terms is another. The classical fleet action is effected by such steps as: knowledge the enemy fleet is at sea, searching and scouting with airplanes and surface vessels over vast ocean areas to locate the main body or the battle fleet; and making submarine and night light-force attacks for purpose of harassment and attrition before the two fleets are proximate. Here strategy is involved to decide where the enemy may be brought to action in localities or under conditions the most favorable to our fleet and with all the combatant forces concentrated. Three senior officers who will make the major general decisions are Commander-in-Chief, U. S. Fleet; Commander Battle Force and Commander Battleship Divisions. Then, when action approaches, the Commander-in-Chief must decide upon his plan of battle, issue the necessary oders to all units, make a deployment of his foree for battle, give the order to commence firing at favorable ranges, make every effort to insure that he will gain command of the air quickly, receive all reports of enemy units sighted, be prepared for certain surprises, keep an accurate picture of his own and enemy units as they shift position and change course at high speed over hundreds of square miles of ocean. He must always maintain maximum concentration of ships and gunfire compatible with flexibility and maneuverability of the various units. Every advantage must be pursued. The traditional American offensive must ever be pushed. Each type, indced each ship, is designed for a specific function, but it is quite impossible to embody in any one type all the defensive and offensive essentials - weight must be sacrificed for speed, and bulk for maneuverability. Somewhere in the design of every ship there is a compromise. The great majority of experts of all naval powers agree that the battleship is the backbone of the fleet. These large, heavily armored vessels with the largestguns pack the great punch and embody the maximum offensive and defense strength of sea power. It is the power of survival combined with enormous striking power that gives the battleship its superior value in a fleet. A battleship is capable of engaging any type met on the high seas, but, of course, should have protection by smaller craft in any zone where submarines may be expected. Modern battleships may have speeds of thirty knots and carry guns up to sixteen-inch caliber. The American Navy has placed armament andarmor ahead of speed in order of desirability. Navy has fifteen battleships organized in four divisions, each of which is commanded by a rear admiral. A vice-admiral commands the entire group, with the title Commander Battleships, Battle Force.The aircraft carrier is for all practical purposes a floating airport or airdrome. Planes take off and fly aboard their broad expanse of decks. Machine shops are found aboard for overhaul and repair work. Spare parts and engines are carried. Cariers must be fast, long-range ships, and depend primarily on other units of the fleet for defense against attack. Their own planes are probably their best defenseagainst air attack. A vice-admiral with the title Commander Aircraft, Battle Force, commands the five carriers assigned to the group. Heavy cruisers came into being as a result of the naval conference after the World War. These vessels of 10,000 tons displacement have long cruising radii, capable of high speed and are equipped with eight-inch guns. Armor has been sacrificed for speed, hence the type depends upon speed and maneuverability to escape from superior enemy forces that may be encountered. This type is effective against enemy cruisers, destroyers, and small craft. They are particularly valuable in locating enemy forces at sea, in raiding and destroying enemy commerce, and in protecting our own merchant ships. We have now eighteen heavy cruisers that are organized in divisions, each commanded by a rear admiral. The light cruiser falls in the category of cruisers of less than 10,000 tons, and mounts six-inch guns. These vessels, like the “heavies,” have long cruising radio and high speed. They are the largest type that carries torpedoes, hence their offensiveduties are somewhat different from either the battleship or the heavy cruiser. They are in a position to attack both battleships and heavy cruisers with torpedoes while with their guns they are capable of break-ing up enemy light force attacks. This class is well suited for commerce destructionand, like the heavy cruisers, are useful for protection of our own commerce. There are nineteen light cruisers in our fleet. The destroyer, equipped with guns, torpedoes, depth charges, and guns of five-inch or less may, if opportunity presentsitself, attack, harry and destroy every type of ship known. Although the smallest of surface craft, the destroyer has more offensive strength per ton than any other type. These hornets of the sea are of superlative speed and are of all types the highest powered per ton displacement. When operating against vessels of larger size the torpedo is the primary weapon of | the destroyer. The United States now has 149 destroyers in commission, of which eight are light mine layers, and eighty-one out of commission. Of the destroyers operating with the fleet today some are of 1,850 tons, some 1,500 and 1,200 tons. The smallest unit for operating destroyers is the division of four ships; three divisions comprise a squadron, and eight squadrons a flotilla. We come next to the submarine, weaponof opportunity, of which much is heard in these days of war. Submarines are designed to travel beneath the surface, and are armed with guns, torpedoes and mines. In the event of hostilities submarines may be used for scouting; that is, locating enemy vessels, observing enemy ports and coasts, and operating against enemy commerce. In any strictly defensive employment, submarines would lay mines and patrol our coasts. If the opportunity came or could be created, submarines would, in a fleet action, attack enemy capital ships. The best defense against the submarine is to keep it down. This is best accomplished by fast destroyers or patrol vessels making depth-charge attacks. The only good submarine is a dead one, or one without torpedoes. The submarine makes a surprisingly small target and is extremely difficult to hit even at medium ranges, and is the lone wolf of the sea in offensive operations against commerce. The United States Navy has sixty submarines in commission under the Commander-in-Chief, United States Fleet, but organized as a separate force commanded by a rear admiral. There are thirty-six other submarines in reserve.

Popular Mechanics, v. 73, n. 4, 1940

Popular Mechanics, v. 73, n. 4, 1940