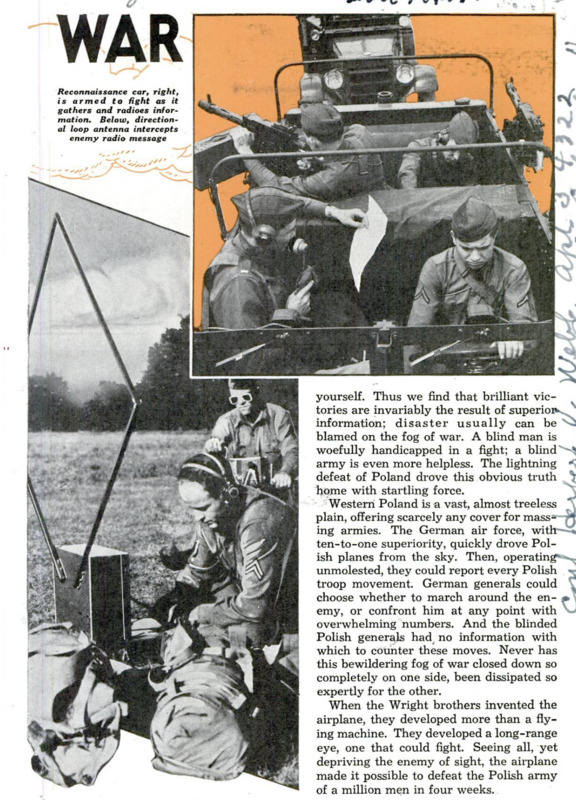

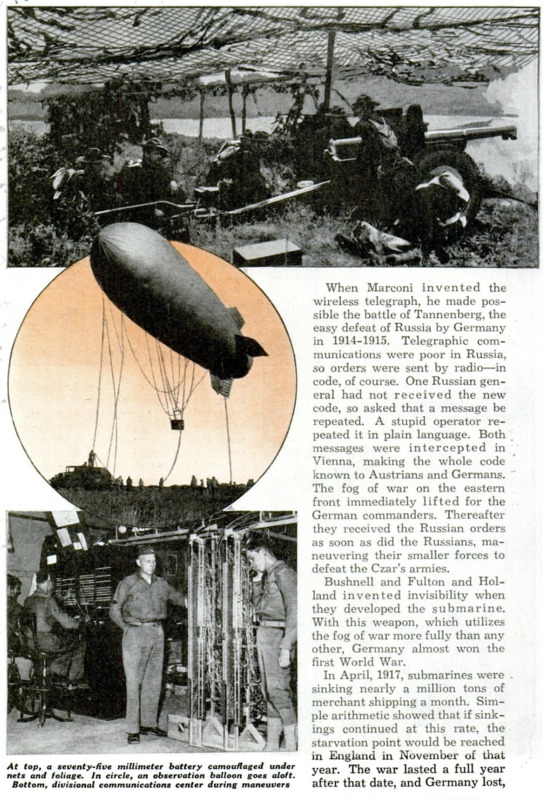

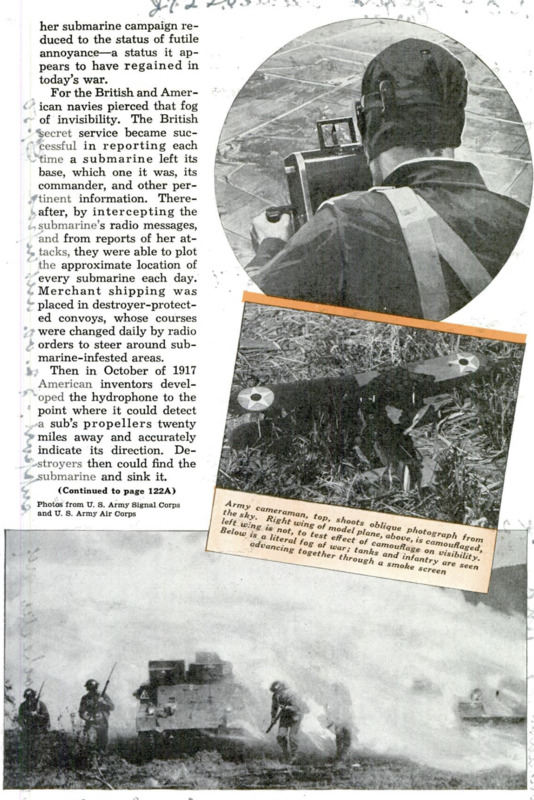

TO THE layman war means bayonets, bombs and bullets. The real war, as waged by successful commanders, is a matter of confusing, deceiving, blinding the opponent, so he will not know where the bayonet, the bomb and the bullet will strike. It is a matter of probing and spying, of efforts to pierce the fog the enemy throws out to blind him. The real war is a matter of censorship, of camouflage, of invention and counter-invention, of patrols and reconnaissance and codes, of everything to deprive the enemy of information, of everything. to obtain information for yourself. Thus we find that brilliant victories are invariably the result of superior information; disaster usually can be blamed on the fog of war. A blind man is woefully handicapped in a fight; a blind army is even more helpless. The lightning defeat of Poland drove this obvious truth home with startling force. Western Poland is a vast, almost treeless plain, offering scarcely any cover for massing armies. The German air force, with ten-to-one superiority, quickly drove Polish planes from the sky. Then, operating unmolested, they could report every Polish troop movement. German generals could choose whether to march around the enemy, or confront him at any point with overwhelming numbers. And the blinded Polish generals had, no information with which to counter these moves. Never has this bewildering fog of war closed down so completely on one side, been dissipated so expertly for the other. When the Wright brothers invented the airplane, they developed more than a flying machine. They developed a long-range eye, one that could fight. Seeing all, yet depriving the enemy of sight, the airplane made it possible to defeat the Polish army of a million men in four weeks. When Marconi invented the wireless telegraph, he made possible the battle of Tannenberg, the easy defeat of Russia by Germany in 1914-1915. Telegraphic communications were poor in Russia, so orders were sent by radio - in code, of course. One Russian general had not received the new code, so asked that a message be repeated. A stupid operator repeated it in plain language. Both messages were intercepted in Vienna, making the whole code known to Austrians and Germans. The fog of war on the eastern front immediately lifted for the German commanders. Thereafter they received the Russian orders as soon as did the Russians, maneuvering their smaller forces to defeat the Czar’s armies. Bushnell and Fulton and Holland invented invisibility when they developed the submarine. With this weapon, which utilizes the fog of war more fully than any other, Germany almost won the first World War. In April, 1917, submarines were sinking nearly a million tons of merchant shipping a month. Simple arithmetic showed that if sinkings continued at this rate, the starvation point would be reached in England in November of that year. The war lasted a full year after that date, and Germany lost, her submarine campaign reduced to the status of futile annoyance - a status it appears to have regained in today’s war. For the British and American navies pierced that fog of invisibility. The British Secret service became successful in reporting each time a submarine left its base, which one it was, its commander, and other pertinent information. Thereafter, by intercepting the submarine’s radio messages, and from reports of her attacks, they were able to plot the approximate location of every submarine each day. Merchant shipping was placed in destroyer-protected convoys, whose courses were changed daily by radio orders to steer around submarine-infested areas. Then in October of 1917 American inventors developed the hydrophone to the point where it could detect a sub’s propellers twenty miles away and accurately indicate its direction. Destroyers then could find the submarine and sink it. The fog of war that the hydrophone pierced now began clamping down on the submarine; for Ralph Brown, another American, perfected the antenna detonator, which made feasible a mine barrage across the North Sea. With 70,000 mines laid across the only channels to the shipping lanes, the submarines faced an invisible menace that broke down the morale of crews, caused the German navy to mutiny. These spectacular examples are duplicated on a smaller scale by the smallest of fighting units. A corporal’s squad of eight has two men permanently designated as scouts, their job in battle being to precede the advance, force the enemy to reveal their position by firing upon them. The success of the sniper, operating alone, depends entirely upon his ability to disguise himself as some part of the normal wartime landscape. A battery of artillery dares not take up position where it can fire directly upon the enemy, for being able to see, it could be seen and destroyed. Instead, it hides behind hill or woods, while an observer in airplane, balloon, or high ground directs its fire by telephone or radio. Even then, the guns must be elaborately camouflaged against aerial observation. Even perfect concealment is protection for only a limited time. Aerial observers can spot the flash of a hidden gun. This failing, a pair of sound-detector squads, operating in unison, can determine the gun position by triangulation. The field telephone and portable radio are indispensable to a commander, but it is difficult to keep communications private. Wires laid parallel with the line a considerable distance away may pick up the conversation by induction, and radio messages are easily intercepted. Sometimes a lack of knowledge on both sides will result in a surprising victory for one or the other. Typical is the case of a World War attack by the Germans on a sector held by American forces south of the Marne. Just at midnight of July 14, 1918, blasts from a thousand German guns ripped the silence of the front. A major in the 30th Infantry picked up his field telephone to warn his battalion of the attack, but the line was dead. Rockets were sent up, calling for counter artillery fire. Runners, dispatched to direct front-line companies to hold their positions and to report how the battle was going, never returned. Then runners arrived from the front, one reporting that two platoons of his company had been wiped out. About dawn the major reached regimental headquarters and reported to his colonel that two of his companies were lost, no trace of them had been found since the attack began. Up at the front, a lieutenant commanding one of the “wiped out” platoons diagnosed the attack as a “good sized raid" - lack of communications prevented him knowing the full extent of the attack. The lieutenant held on at his position until he could bring back 150 enemy soldiers to the colonel. Later the colonel learned, to his further surprise, that the companies reported by the major as “lost” had stopped the great offensive cold. The Germans were equally in the dark as to what was happening. One major, confident the battle was won, led his battalion in close column along a road at daybreak and it was annihilated by surprise fire from that other platoon which had been reported as “wiped out.” So, in spite of all precautions and scores of inventions to pierce the fog of war, obscurity and confusion are still normal on the battlefield. An army text warns officers that “late, exaggerated or misleading information, surprise situations, are to be expected. The normal is abnormal, and uncertainty is certain.”