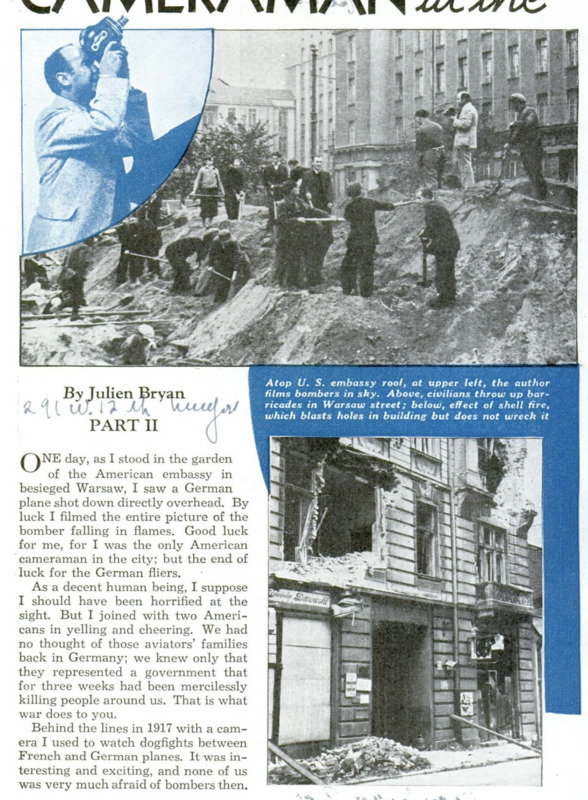

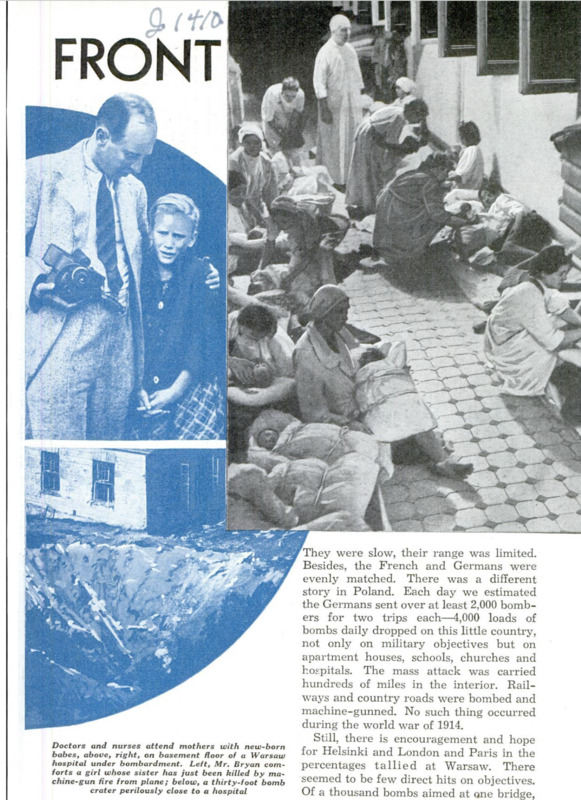

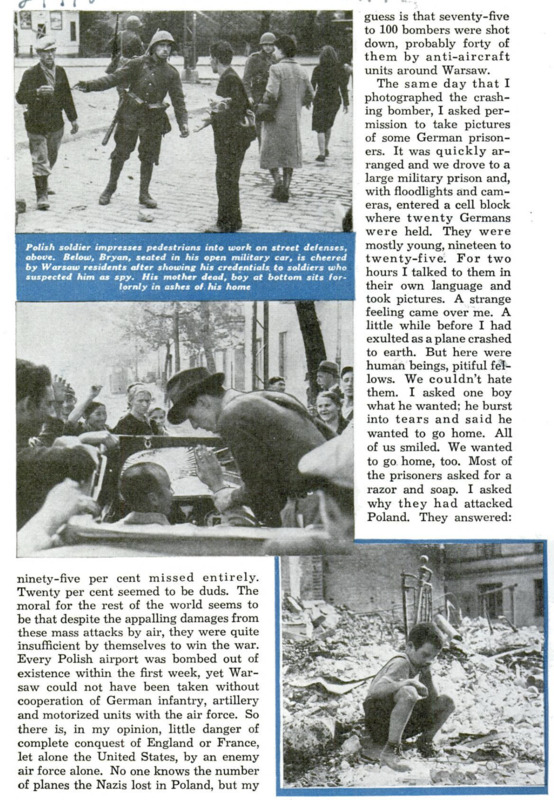

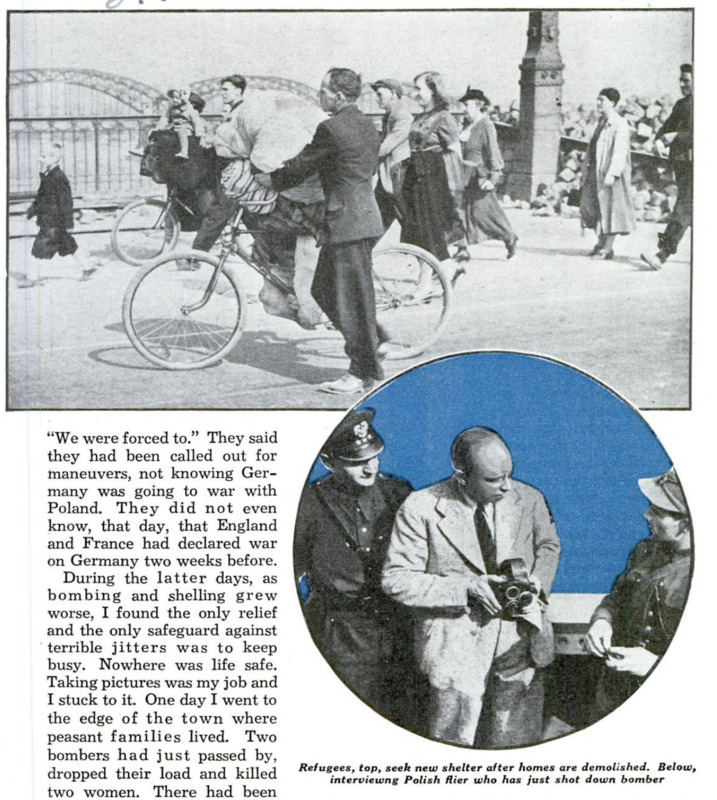

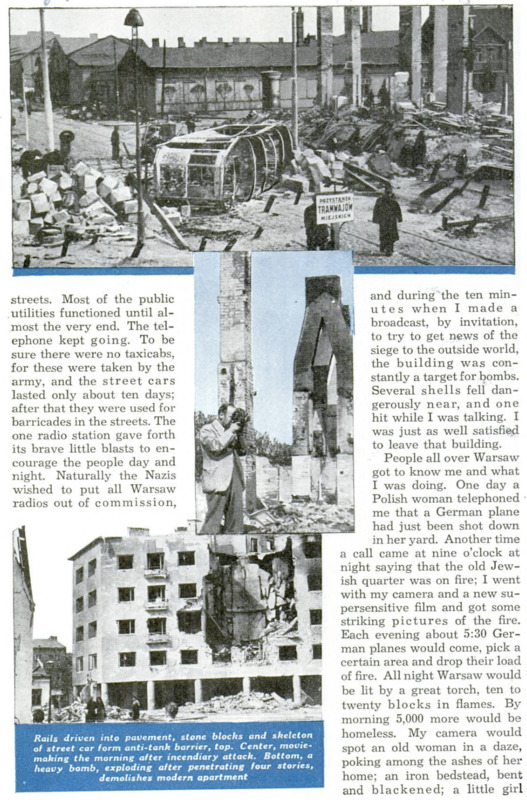

ONE day, as Istood in the garden of the American embassy in besieged Warsaw, I saw a German | plane shot down directly overhead. By luck I filmed the entire picture of the bomber falling in flames. Good luck for me, for I was the only American cameraman in the city; but the end of luck for the German fliers. As a decent human being, I suppose 1 should have been horrified at the sight. But I joined with two Americans in yelling and cheering. We had no thought of those aviators’ families back in Germany; we knew only that they represented a government that for three weeks had been mercilessly killing people around us. That is what war does to you. Behind the lines in 1917 with a cam-era I used to watch dogfights between French and German planes. It was interesting and exciting, and none of us was very much afraid of bombers then. They were slow, their range was limited. Besides, the French and Germans were evenly matched. There was a different story in Poland. Each day we estimated the Germans sent over at least 2,000 bombers for two trips each - 4,000 loads of bombs daily dropped on this little country, not only on military objectives but on apartment houses, schools, churches and hospitals. The mass attack was carried hundreds of miles in the interior. Railways and country roads were bombed and machine-gunned. No such thing occurred during the world war of 1914. Still, there is encouragement and hope for Helsinki and London and Paris in the percentages tallied at Warsaw. There seemed to be few direct hits on objectives. Of a thousand bombs aimed at ane bridge, ninety-five per cent missed entirely. Twenty per cent seemed to be duds. The moral for the rest of the world seems to be that despite the appalling damages from these mass attacks by air, they were quite insufficient by themselves to win the war. Every Polish airport was bombed out of existence within the first week, yet Warsaw could not have been taken without cooperation of German infantry, artillery and motorized units with the air force. So there is, in my opinion, little danger of complete conquest of England or France, let alone the United States, by an enemy air force alone. No one knows the number of planes the Nazis lost in Poland, but my guess is that seventy-iive to 100 bombers were shot down, probably forty of them by anti-aircraft units around Warsaw. The same day that photographed the crashing bomber, I asked permission to take pictures of some German prisoners. It was quickly arranged and we drove to a large military prison and, with floodlights and cameras, entered a cell block where twenty Germans were held. They were mostly young, nineteen totwenty-five. For two hours I talked to them in their own language and took pictures. A strange feeling came over me. A little while before I had exulted as a plane crashed to earth. But here were human beings, pitiful fellows. We couldn’t hate them. I asked one boy what he wanted; he burst into tears and said he wanted to go home. All of us smiled. We wanted to go home, too. Most of the prisoners asked for a razor and soap. I asked | why they had attacked Poland. Thev answered: “We were forced to.” They said they had been called out for maneuvers, not knowing Germany was going to war with Poland. They did not even know, that day, that England and France had declared war on Germany two weeks before. During the latter days, as bombing and shelling grew worse, I found the only relief and the only safeguard against terrible jitters was to keep busy. Nowhere was life safe. Taking pictures was my job and I stuck to it. One day I went to the edge of the town where peasant families lived. Two bombers had just passed by, dropped their load and killed two women. There had been seven women in a field digging potatoes. Frightened, they had run in all directions, but the planes flew on, and the women, hungry, went back to their potatoes. In fifteen minutes the planes returned, powedived, and as they drove past close to the ground they opened machine-gun fire and killed two more women. A few minutes later, as I finished filming the scene, a little girl of eleven or twelve came running up. Kneeling beside her dead sister, a girl of twenty, she cried: “Oh, my sister, talk to me. Please come back to me, my sister!” She could not understand. I took a series of pictures, but finally could take no more. I put my arm around the little girl and tried to comfort her, but I cried, too, and so did the Polish soldiers with me. Life must go on for those that survive. The women went back to their digging in the potato field. Nurses in the hospitals carried on while bombs fell. Few of the stores in Warsaw closed, unless they were wrecked. Even the newsboys stuck to their jobs while shells raked the principal streets. Most of the public utilities functioned until almost the very end. The telephone kept going. To be sure there were no taxicabs, for these were taken by the army, and the street cars lasted only about ten days; after that they were used for barricades in the streets. The one radio station gave forth its brave little blasts to encourage the people day and night. Naturally the Nazis wished to put all Warsaw radios out of commission, and during the ten minutes when I made a broadcast, by invitation, to try to get news of the siege to the outside world, the building was constantly a target for bombs. Several shells fell dangerously near, and one hit while I was talking. I was just as well satisfied to leave that building. People all over Warsawgot to know me and what I was doing. One day a Polish woman telephoned me that a German plane had just been shot down in her yard. Another time a call came at nine o'clock at night saying that the old Jewish quarter was on fire; I went with my camera and a new supersensitive film and got somestriking pictures of the fire. Each evening about 5:30 German planes would come, pick a certain area and drop their load of fire. All night Warsaw would be lit by a great torch, ten to twenty blocks in flames. By morning 5,000 more would be homeless. My camera would spot an old woman in a daze, poking among the ashes of her home; an iron bedstead, bent and blackened; a little girl clutching her dog; two boys reading a Polish edition of Mickey Mouse. All these people saved first of all their bedclothes and a little food. You had to keep warm, you had to eat. Thousands cooked and slept outdoors. I am not primarily a war correspondent, but a peacetime reporter with a camera, going around the world photographing people. That is what I tried to do in Warsaw, and would do at any front.. The great story there was what happened to the old men, the mothers, the babies, the civilians who kept at their jobs. The pictures of which I am proudest are the closeups of a brave people in agony. All this time, of course, we Americans and other foreigners scarcely dared think whether we would ever escape from the encircled city. Mayor Starzynski said to me one day that “it would be a wonderful thing for Poland if your films could be taken out now. Then the world would know what the Nazis have done to Warsaw. If we can get you a plane, would you care to go?” I nodded. The mayor sent an aviation officer to the nearest field to try to get a plane. He never returned. Then at 1:30 on the afternoon of Sept. 21 came the news that from two to five o’clock hostilities would cease and all foreigners would be evacuated. No one was permitted to take more than one small suitcase, and I had to leave behind $2,000 worth of cameras and equipment. Films took up most of the space in my bag, so I forsook also nearly all clothing. Promptly at two, some fifty automobiles and eighty army trucks assembled. We waited two hours for stragglers, until there were 1,200 of us, of thirty nationalities. Not until 4:30, a half hour before the truce was to end, did the trek start. We passed a mile of ruined houses, occasionally saw a half-hidden three-inch gun, Three and a half miles from Warsaw’s center were the Polish front lines, beyond that, No Man’s Land. Gunners crouched quietly in shallow trenches. Five hundred yards back of them children were playing. We debarked from the cars and started across the quiet battlefield on foot. Seeing a Polish-American woman struggling with her crying baby, trying to readjust her hold on a bulky suitcase, I put down my bag and went to her aid. When I returned, it was gone - with it my precious films! At last we could distinguish German soldiers in the distance. Reaching their lines, we were loaded into trucks and three hours later had covered the twenty-five miles to Nasielsk, where a train awaited us. Next morning at nine o’clock we arrived at Konigsberg, and for many of us fears became critical. Those whose papers were not in order, were afraid they might be headed for concentration camps. As for me, I had been quoted in the Warsaw press, had talked over the radio, and my earlier documentary films of Nazi Germany were known in Berlin. I was not at all happy. I had even lost my films.

Then, the following morning, against a wall in the lobby of a hotel, there was my suitcase. I don’t know yet how it got there.Unostentatiously as possible I picked it up. Not one film was missing! Three small rolls I particularly wished to save I slipped into my pocket. I mentioned my problem to an American girl, and she solved it for me. From anotherAmerican who had been very unobliging to her, she borrowed a souvenir gas mask, hid the three films in its chemical chamber, and handed it back to the man. If it were searched, he would have some explaining to do. It wasn’t; later the girl again borrowed the mask, retrieved the films and a month later gave them to me in New York. The man never knew how helpful he was. One thing I knew I should not do - that was to travel to Berlin with the rest of these Warsaw ‘“refugees.” For there I would surely be discovered. Learning that a group of Swedes were leaving by train for Riga, I contrived to disappear from my American friends - who thought I had been taken into custody - joined the Swedes and in a few hours was across the border in Lithuania, my bag of films intact. All the rest of my life, when I emerge from a trying situation, I'll say to myself: “Now you've crossed into Lithuania.”

Popular Mechanics, v. 73, n. 4, 1940

Popular Mechanics, v. 73, n. 4, 1940