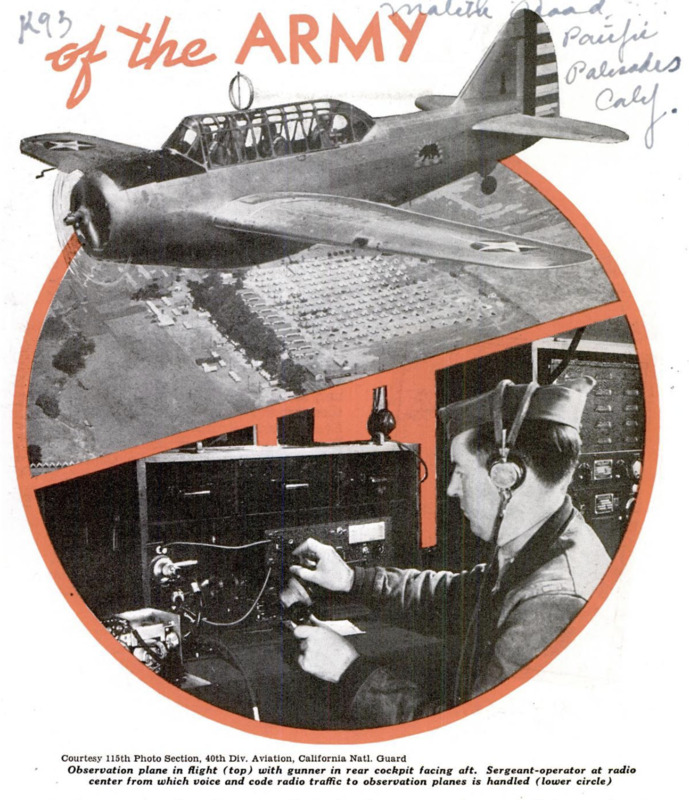

The "Flying Eyes" of the Army

Contenuto

- Titolo

- The "Flying Eyes" of the Army

- Article Title and/or Image Caption

- The "Flying Eyes" of the Army

- Lingua

- eng

- Copertura temporale

- World War II

- Data di rilascio

- 1940-05

- pagine

- 668-670, 146A, 149A

- Diritti

- Public Domain (Google digitized)

- Sorgente

- Google books

- Archived by

- Enrico Saonara

- Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

- Copertura territoriale

- United States of America