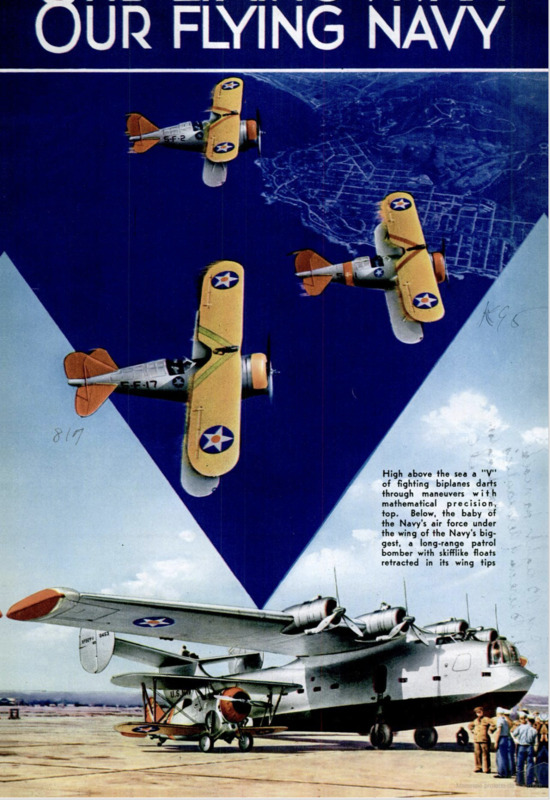

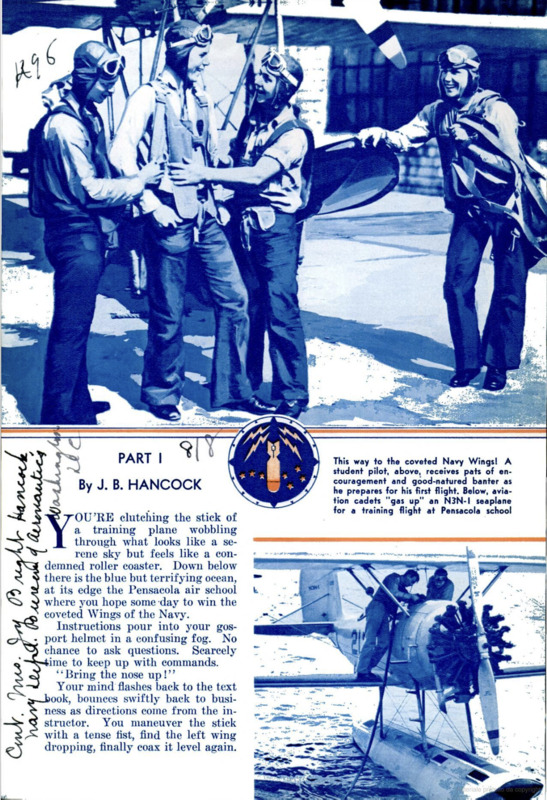

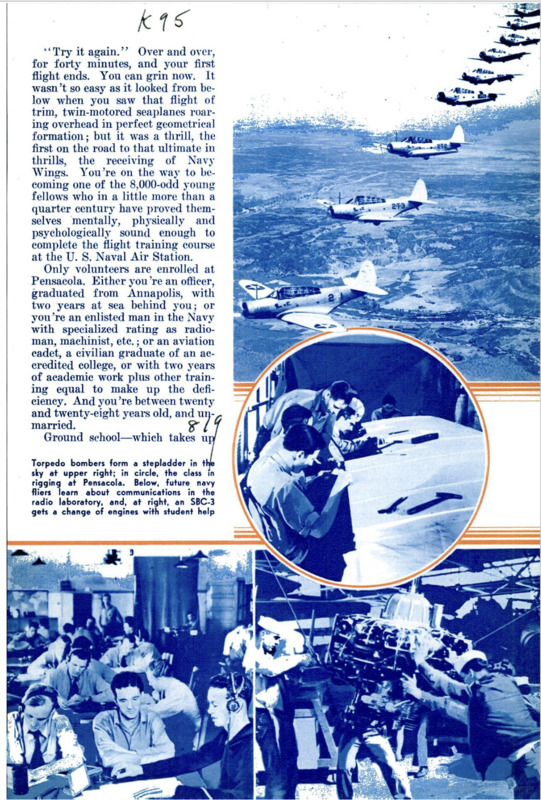

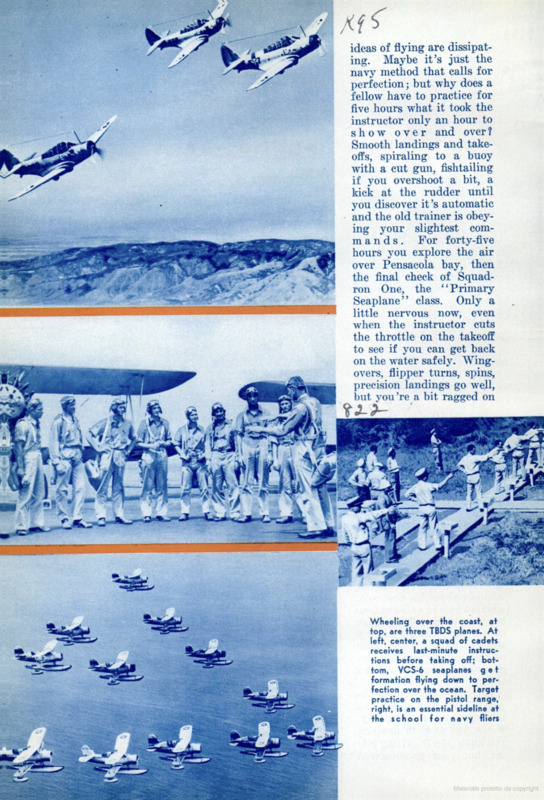

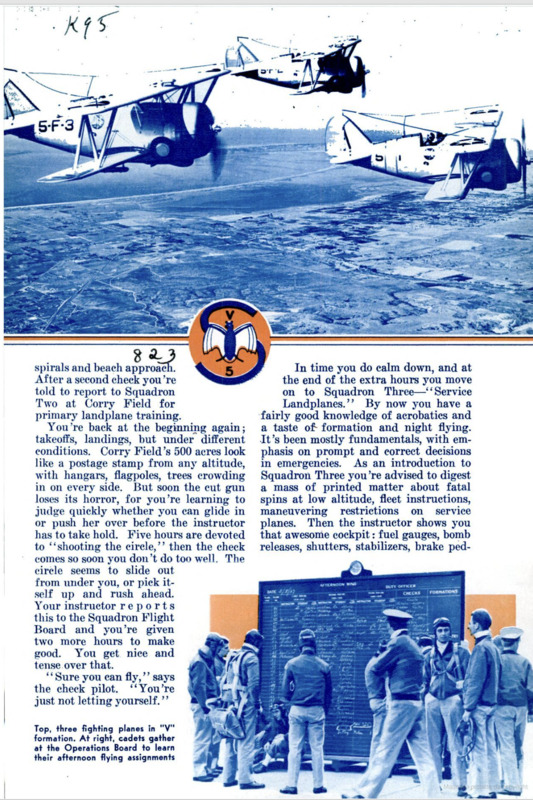

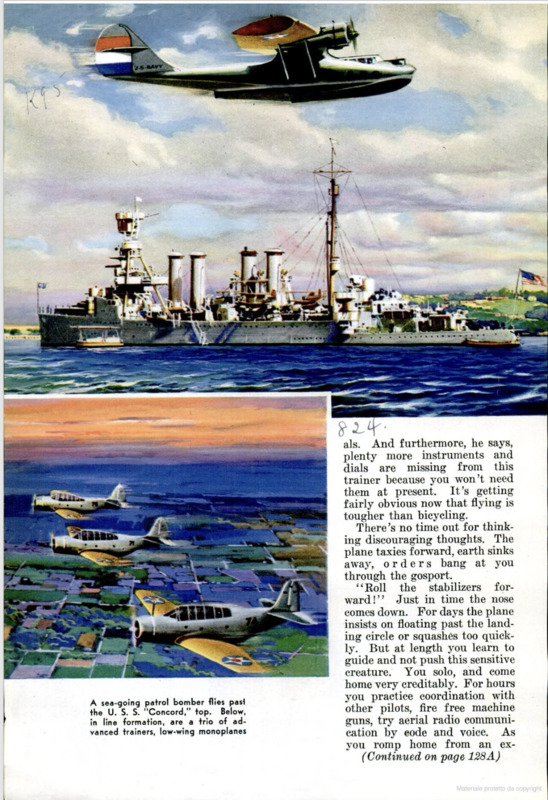

YOU’RE clutehing the stick of a training plane wobbling through what looks like a serene sky but feels like a condemned roller coaster. Down below there is the blue but terrifying ocean, at its edge the Pensacola air school where you hope someday to win the coveted Wings of the Navy. Instructions pour into your gosport helmet in a confusing fog. No chance to ask questions. Scarcelytime to keep up with commands. “Bring the nose up!” Your mind flashes back to the text book, bounces swiftly back to business as directions come from the instructor. You maneuver the stick with a tense fist, find the left wing dropping, finally coax it level again, “Try it again.” Over and over, for forty minutes, and your first flight ends. You can grin now. It wasn’t so easy as it looked from below when you saw that flight of trim, twin-motored seaplanes roaring overhead in perfect geometrical formation but it was a thrill, the first on the road to that ultimate in thrills, the receiving of Navy Wings. You're on the way to becoming one of the 8,000-odd young fellows who in a little more than a quarter century have proved themselves mentally, physically and psychologically sound enough to complete the flight training course at the U. S. Naval Air Station. Only volunteers are enrolled at Pensacola. Either you're an officer, graduated from Annapolis, with two years at sea behind you or you're an enlisted man in the Navy with specialized rating as radioman, machinist, etc.; or an aviation cadet, a civilian graduate of an accredited college, or with two years of academic work plus other training equal to make up the deficiency. And you’re between twenty and twenty-eight years old, and unmarried Ground school - which takes up engines, gunnery, photography, communications, aircraft structures, acrology and navigation - starts simultaneously with flight training. The pace is fast. Once you ean keep that little trainer seaplane on a reasonably straight course you're told to bank and land. The plane never seems to act the same way twice. For a week you bank and turn, land, take off ; then your instructor tells you, surprisingly, that you're ready to solo. A check pilot, stranger to you, elimbs in, administers crisp advice about relaxing to get the feel of the plane, grins encouragement and you're taxiing across the bay. You do some of your worst flying under the strain, but the check pilot - familiar with the disease of ‘‘checkitis” - says a few calming words and you actually make a ereditable landing. Out steps the check pilot, calling: “All right, take her around the course.” You’re on your own! But, up in the air, you find yourself so busy you have to postpone a feeling of thrill until you’re down again. Twenty minutes later your record is marked ‘‘Completed solo flight satisfactorily.” The big hurdle is behind! Following time-honored custom, classmates toss you bodily into Pensacola bay. It’s the fate of every student who completes his first solo, whether he’s an enlisted man or a four-striper. The plunge seems to loosen every strained muscle, every kink of the brain. From here on no problem can be too hard to lick. But the next few weeks you alternate between triumph and despondency. When you stop to analyze, you know you're getting better, but your preconceived ideas of flying are dissipating. Maybe it’s just the navy method that calls for perfection; but why does a fellow have to practice for five hours what it took the instruetor only an hour to show over and over? Smooth landings and takeoffs, spiraling to a buoy with a cut gun, fishtailing if you overshoot a bit, a kick at the rudder until you discover it’s automatic and the old trainer is obeying your slightest commands. For forty-five hours you explore the air | over Pensacola bay, then the final check of Squadron One, the ‘‘Primary Seaplane” class. Only a little nervous now, even when the instructor cuts the throttle on the takeoff to see if you can get back on the water safely. Wing- overs, flipper turns, spins, precision landings go well, but you’re a bit ragged on spirals and beach approach. After a second check you're told to report to Squadron Two at Corry Field for primary landplane training. You're back at the beginning again takeoffs, landings, but under different conditions. Corry Field’s 500 acres look like a postage stamp from any altitude, with hangars, flagpoles, trees crowding in on every side. But soon the cut gun loses its horror, for you're learning to judge quickly whether you ean glide in or push her over before the instructor has to take hold. Five hours are devoted to “shooting the circle,” then the check comes so soon you don’t do too well. The circle seems to slide out from under vou, or pick itself up and rush ahead. Your instructor reports this to the Squadron Flight Board and you're given two more hours to make good. You get nice and tense over that. “Sure you can fly,” says the check pilot. “You're just not letting yourself.” In time you do calm down, and at the end of the extra hours you move on to Squadron Three - ”Service Landplanes.” By now you have a fairly good knowledge of acrobatics and a taste of formation and night flying. It’s been mostly fundamentals, with emphasis on prompt and correct decisions in emergencies. As an introduction to Squadron Three you’re advised to digest a mass of printed matter about fatal spins at low altitude, fleet instructions, maneuvering restrictions on service planes. Then the instructor shows you that awesome cockpit : fuel gauges, bomb releases, shutters, stabilizers, brake pedals. And furthermore, he says, plenty more instruments and dials are missing from this trainer because you won’t need them at present. It’s getting fairly obvious now that flying is tougher than bicyeling. There’s no time out for thinking discouraging thoughts. The plane taxies forward, earth sinks away, orders bang at you through the gosport. “Roll the stabilizers forward!’’ Just in time the nose comes down. For days the plane insists on floating past the landing cirele or squashes too quickly. But at length you learn to guide and not push this sensitive creature. You solo, and come home very ereditably. For hours you practice coordination with other pilots, fire free machine guns, try aerial radio communication by eode and voice. As vou romp home from an extended flight by dead reckoning you see beginners struggling around the bay in primary seaplanes, and realize you've come a long way. Looking ahead toward the time when you'll be flying over hundreds of miles of water, where every wave looks alike and navigating ability means life or death, you tackle instrument flying with zest and move up confidently to Squadron Four and its twin-engined flying boats. Now you look over at close hand the huge seaplane that stirred your first desire to fly. The instructor says you are to do horizontal bombing, navigate at sea and fix positions by dead reckoning and celestial navigation. But first, to fly the boat. The old familiar stick is now a wheel. And you sense that all these tons won't answer so quickly to the controls. At last you're allowed to take it up, and you feel that you're flying the hangar itself. In six hours you're able to lift her off the water properly and land, taxiing on one motor despite wind and current. Time now to try practical application of the textbook on bombing. With a fellow student at the controls, 10,000 feet up, you kneel over the bomb sight to find the barely visible target, turn the knobs till you're “on,” pull the toggle and the bomb drops. Down, down, nearly two miles, then a splash, Generally a miss, but soon enoughcome the thrills of perfect hits. Later on there’s fun, if it is tough, in navigational problems - “Find your object, whereabouts unknown.” And as a parting test in “Advanced Seaplanes” you ride the catapult. Taking the instructor’s advice you relax and don’t try to fly the plane till it’s in the air. It isn’t a very long wait! Squadron Five, “Advanced Landplanes,” puts you in a single-seat fighter, and for the first time you take up a new-type plane without friendly advice coming in through your gosport. Single-seater tactics call for the highest physical and mental coordination. After grueling hours of drill you're able to put on an acceptable show of advanced acrobatics for the official board, but you have to do a full repeat simply because you neglected to notice that some clouds obscured your best snap rolls and some perfect loops. In the encore performance you even remember not to get between the sun and your instructors. Dive bombing and fixed gunnery technique, advanced tactics in low-wing monoplanes - including high-altitude flight - and aerial torpedo dropping are mastered along with learning what to do with all the speed that’s now at your command. Just as you think you know all there is to know, you're told to finish up the instrument-flying course, which will give you a Scheduled Air Transport rating. So you arrive at a point where you can actually look back. It has been exhausting work, clouded by many a day of dark depression but with never a dull moment and with certain highspots of encouragement that will always sparkle in your memory. All the while you've been driving, driving toward one goal - a word from the commandant that you have met the test. And at last the summons comes. Every man of your class who has been able to climb along with you through the five training squadrons assembles before the officers. Proud, in best uniforms that reflect inner exhilaration, you all look fondly toward the stock of little white boxes that hold the coveted Navy Wings. The admiral is pinning one on the lad next to you, and now, rigidly at attention, you hear the sharp point prick the starched white fabric of your own uniform coat. A hand is thrust into yours in firm clasp, and as you look up you notice a pair of wings like your own on the commandant’s coat. “Why,” it suddenly occurs to you, “he’s gone through all of this himself.” The commandant proceeds down the line. At the end he steps back a few paces and addresses the class: “Gentlemen, I am happy to present you with your Navy Wings, for you haveearned them. Your work here at Pensacola has prepared you for what you must learn in carrying out your tasks in the fleet. You now belong to that group of officers known as naval aviators. Your predecessors have established a high standard of efficiency, progress and safety. They have made naval aviation what it is today.It is your duty to live up to that standard and contribute to it. It is a difficult assignment but I believe you can do it. I congratulate you and wish you a happy cruise, Report to my office for orders.”

Popular Mechanics, v. 73, n. 6, 1940

Popular Mechanics, v. 73, n. 6, 1940