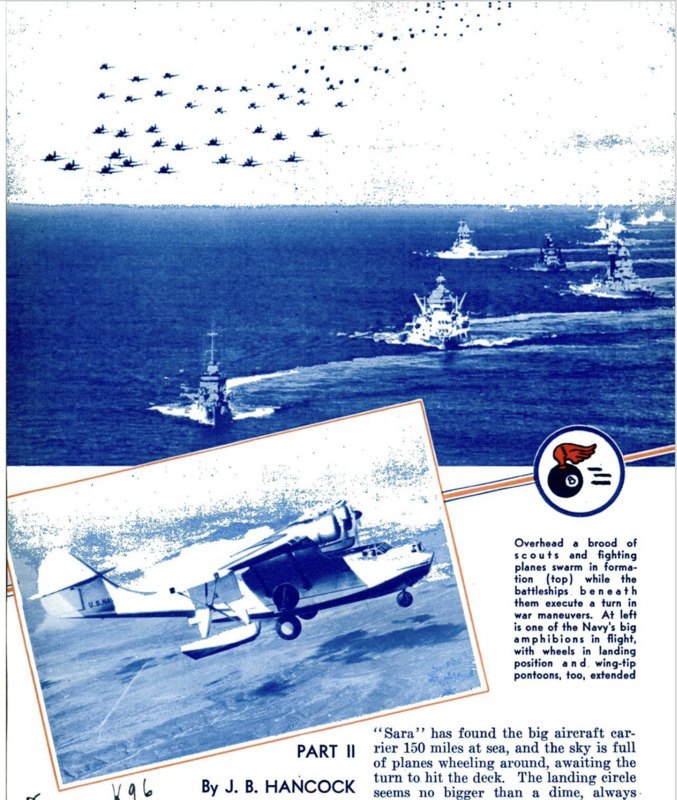

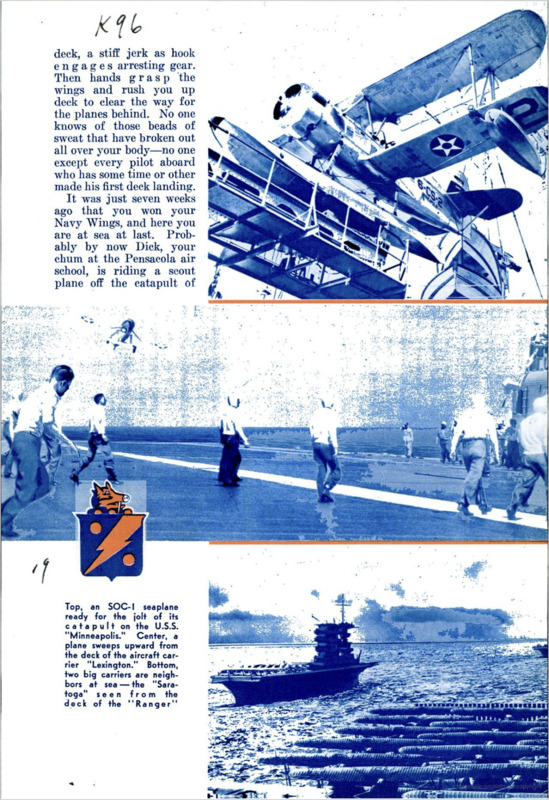

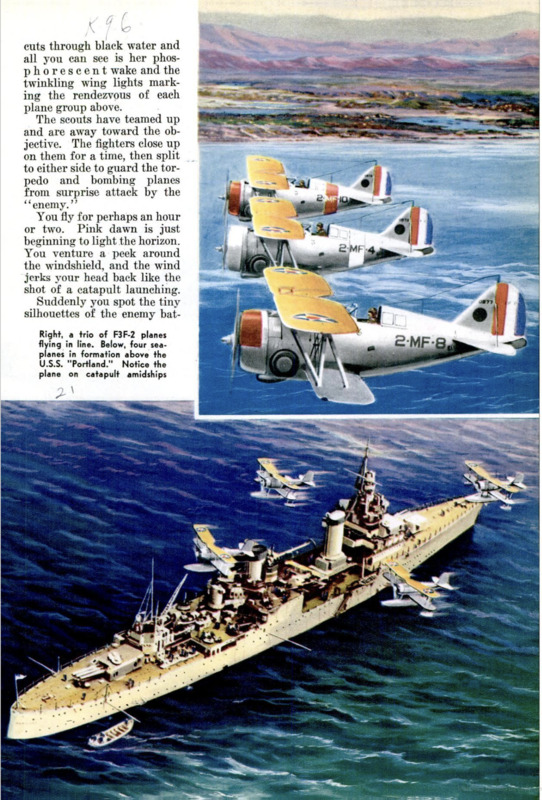

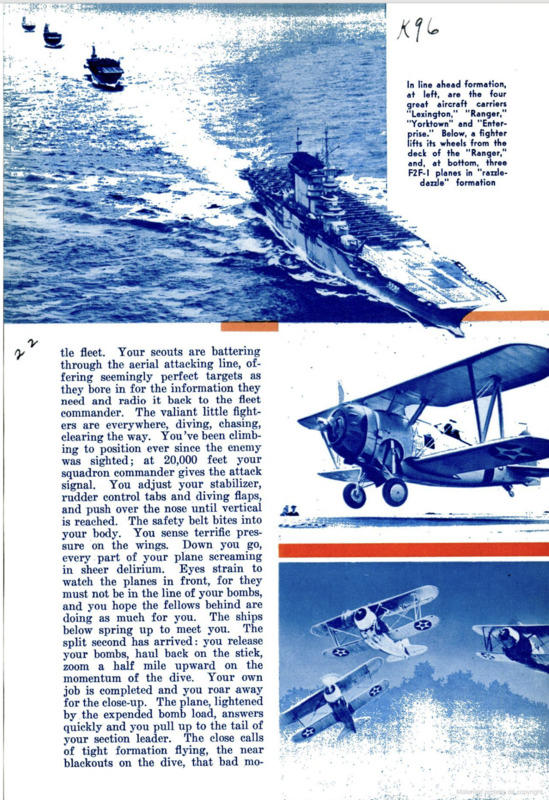

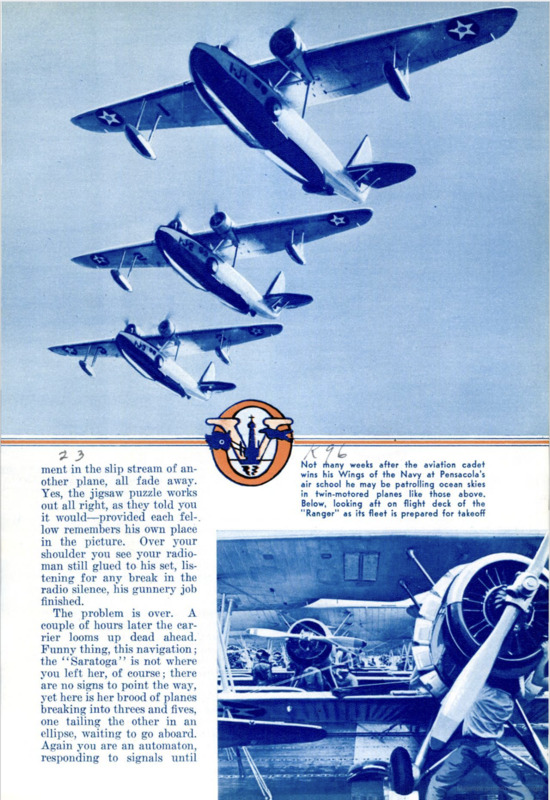

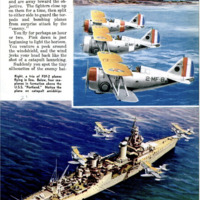

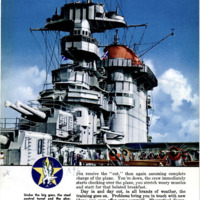

FROM your bombing plane 3,000 feet up, the 888-foot landing deck of the ‘‘Saratoga” looks like a match stick tossing on the waves. For three weeks you've practiced landing on a eircle at the San Diego Naval Air Station, but this is different. The new brood of bombers assigned to the “Sara’’ has found the big aircraft carrier 150 miles at sea, and the sky is full of planes wheeling around, awaiting the turn to hit the deck. The landing circle seems no bigger than a dime, always moving, rolling, pitching. The planes ahead have landed like clockwork, without a single wave-off. It’s your turn next. Snap open the parachute harness, lower the arresting hook, flaps in position. Down you come, lower and lower, leveling off as you come over the stern. The signal officer waves you on. Right ip the groove ; a slight jar as wheels touch deck, a stiff jerk as hook engages arresting gear. Then hands grasp the wings and rush you up deck to clear the way for the planes behind. No one knows of those beads of sweat that have broken out all over your body - no one except every pilot aboard who has some time or other made his first deck landing. It was just seven weeks ago that you won your Navy Wings, and here you are at sea at last. Probably by now Dick, your chum at the Pensacola air school, is riding a seout plane off the catapult of the cruiser ‘‘Philadelphia’’ while Harry is piloting a flying boat with Patrol Squadron 23 at Hawaii. First major problem of your cruise comes after only a weck on the “Saratoga.” At 2:30 a.m. the signal to flight quarters brings aviators on the double-quick to the “Ready-Room” for a steaming eup of coffee and last-minute instructions - their object, probable distance, disposition of planes. Word comes from the cruiser scouting planes that the “enemy’’ has not been located in certain areas. Over the loud speaker comes the command: ‘‘Man your planes!” Out on the flight deck the pilots weave among parked planes, ghostly forms in the eerie light of blue flames from seventy-five engine exhausts, The roar of thousands of horsepower and the whirling propellers is terrific. Already the scout planes are tearing down the deck, one by one, darting off into an inky black sky; bombers and torpedo planes follow in quick succession, then tiny single-seat fighters scream across the bow and climb away. The carrier, with her guardian destroyers close aft, cuts through black water and all you ean see is her phosphorescent wake and the twinkling wing lights marking the rendezvous of each plane group above. The seouts have teamed up and are away toward the objective. The fighters close up on them for a time, then split to either side to guard the torpedo and bombing planes from surprise attack by the “enemy.” You fly for perhaps an hour or two. Pink dawn is just beginning to light the horizon. You venture a peek around the windshield, and the wind jerks your head back like the shot of a catapult launching. Suddenly you spot the tiny silhouettes of the enemy battle fleet. Your scouts are battering through the aerial attacking line, offering seemingly perfect targets as they bore in for the information they need and radio it back to the fleet commander. The valiant little fighters are everywhere, diving, chasing, clearing the way. You’ve been climbing to position ever since the enemy was sighted; at 20,000 feet your squadron commander gives the attack signal. You adjust your stabilizer, rudder control tabs and diving flaps, and push over the nose until vertical is reached. The safety belt bites into your body. You sense terrific pressure on the wings. Down you go, every part of your plane sereaming in sheer delirium. Eyes strain to watch the planes in front, for they must not be in the line of your bombs, and you hope the fellows behind are doing as much for you. The ships below spring up to meet you. The split second has arrived: you release your bombs, haul back on the stick, zoom a half mile upward on the momentum of the dive. Your own job is completed and you roar away for the close-up. The plane, lightened by the expended bomb load, answers quickly and you pull up to the tail of your section leader. The close ealls of tight formation flying, the mear blackouts on the dive, that bad moment in the slip stream of another plane, all fade away. Yes, the jigsaw puzzle works out all right, as they told you it would - provided each fel-low remembers his own place in the picture. Over your shoulder you see your radioman still glued to his set, listening for any break in the radio silence, his gunnery job finished. The problem is over. A couple of hours later the carrier looms up dead ahead. Funny thing, this navigation ; the ‘‘Saratoga’’ is not where you left her, of eourse; there are no signs to point the way, yet here is her brood of planes breaking into threes ard. fives, one tailing the other in an ellipse, waiting to go aboard. Again you are an automaton, Responding to signals until you receive the “‘cut,”’ then again assuming complete charge of the plane. You’re down, the crew immediately starts checking over the plane, you stretch weary museles and start for that belated breakfast. Day in and day out, in all brands of weather, the training goes on. Problems bring you in touch with new ideas; you even offer some yourself. Theoretical discussions are followed by practical tryouts. Finally during one night watch you move in on Hawaii. But you’re on maneuvers, and a mock battle is fought before you are allowed to anchor. Patrol planes protecting the ‘‘Paradise of the Pacific’” da a lot of theoretical damage to some of your ships before that time. Then shore leave, and a rendezvous with Dick and Harry. Their. versions of the big problem supply the missing pieces of the picture. “You can’t imagine the thrill of advanced scouting from the cruisers,” Dick tells you, “until you've done it. You carrier birds make a lot of noise and blow big holes, but it was my gang that told you where not to waste time looking for the enemy. It starts with the kick of the catapult, and from there on you’re a pair of flying eyes; and when those eyes find the enemy you're set for a busy time. You're dodging enemy planes, radioing details of numbers, types, speeds, directions, probable intention, and at the same time you're trying to keep out of range of anti-aircraft guns. You fly as long as your gas gauge shows enough to get back to your ship, and how those cruisers move around in your absence!” The battleship planes have their own big problem, too. While the dreadnaughts are blasting away, the planes sit up near the clouds radioing instructions for the gunners; and when the ships are not even in sight it’s no easy task to determine which ship is firing short or over the target, and to coach that ship on to the mark. Harry, who was graduated from Pensacola to a flying bomber on Hawaiian patrol duty, has another story to tell. “We scout for thousands, not hundreds of miles,” Harry relates. “And what's more, when we find what we're looking for we go right in and do an attack job. The big boats are ready to fight far ahead of the fleet and its flock of ‘homing pigeons’.” Your patrol squadrons, he says, are operated as tactical units, and on a scouting job during fleet exercises you're one of a group of iwelve planes lanned out to cover a line several hundred miles long. You must keep that line precise and exactly abreast, even though you can’t see one another and radio silence prevails. That means the most exact brand of navigation. The first to sight the objective breaks radio silence and calls a rendezvous. If you'vemeasured your drift exactly, kept your bubble octant working well enough to give confirming lines of position, or gotten radio bearing, you're set. But it's never that easy. Fog, overcast, atmospheric conditions always complicate things. You check on the dead reckoning at every opportunity. When off duty as pilot you do the navigating, while your relief watches the instruments and the automatic pilot. One man is always on duty as radio operator, a mechanic constantly watches engine indicators. There’s no relaxing. Flying is the easiest part of the show. It's the landings that generally beat you down. The squadron returns from a twenty-four hour jaunt to find a sudden fog over the harbor. There you are, blind as a bat, above a fifty-foot ceiling. On your inter-plane phone you hear your skipper call the ground. The reply snaps back: “Circle until further communication.” For twenty minutes you carry on, straining eye muscles to keep a safe distance from the plane in front. Phantom planes steal up to your wing tips. You wipe imaginary fog from inside your windshield. Then comes the voice from below through the head phones: “Radio-equipped boat is stationed in harbor. We will coach you to landings. Come through the ceiling one at a time.” You get set. “The sound of your motors is directly overhead. Fly three sides of a square, three minutes to a side, to 1,000 feet; then start the fourth side with a glide at the rate of descent of 300 feet per minute.” The first section slants down out of sight. Your section leader starts. Now it’s your turn, Every man is quiet and busy at his. station. Outside, a solid wall of cloud presses against the windows. You follow the instruments with infinite care. Three sides of the square, another right turn, Start your glide. Down, down you go. “You're OK, come on in,” sounds the reassuring voice. You hold your breath as the altimeter reads 100 feet, seventy-five feet, fifty feet, then you break into the clear! In a few seconds you're down, taxiing over the bay, still faintly streaked with the white wakes of preceding planes. You pull out of the landing area quickly. One of your crew is hanging over the nose in a safety belt, boat hook in hand, ready to snag the buoy. Everyone at his routine job. You wonder what they were thinking back there in the ceiling. “The Officer of the Day greets you on the dock with ‘Pretty thick up there, I hear,’” Harry finishes. “You grin back. The OD is an old hand. He’s been up in all types, and he's always told you all planes handle the same in fog, and they all get their share of the breaks, good and bad. Air philosophy, he calls it - the kind that comes with Navy Wings.”