-

Titolo

-

Homing Pigeons on the Night Shift

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Homing Pigeons on the Night Shift

-

extracted text

-

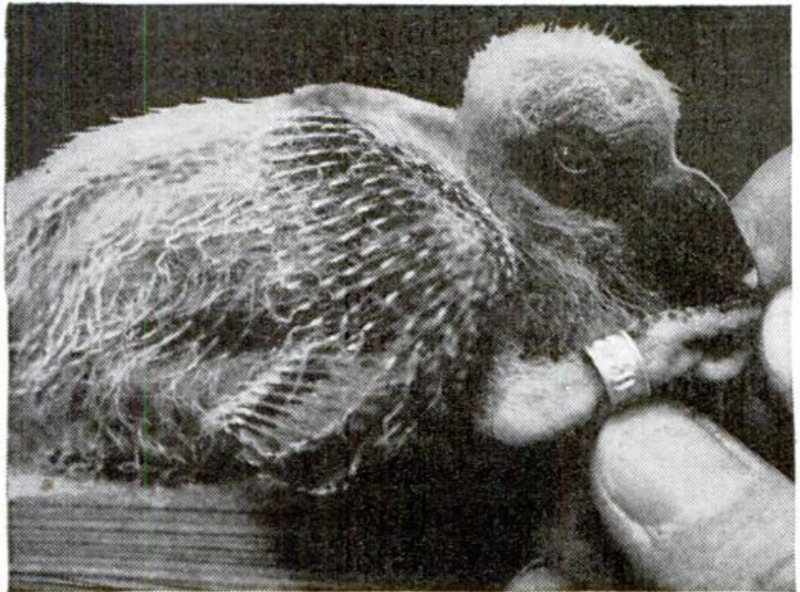

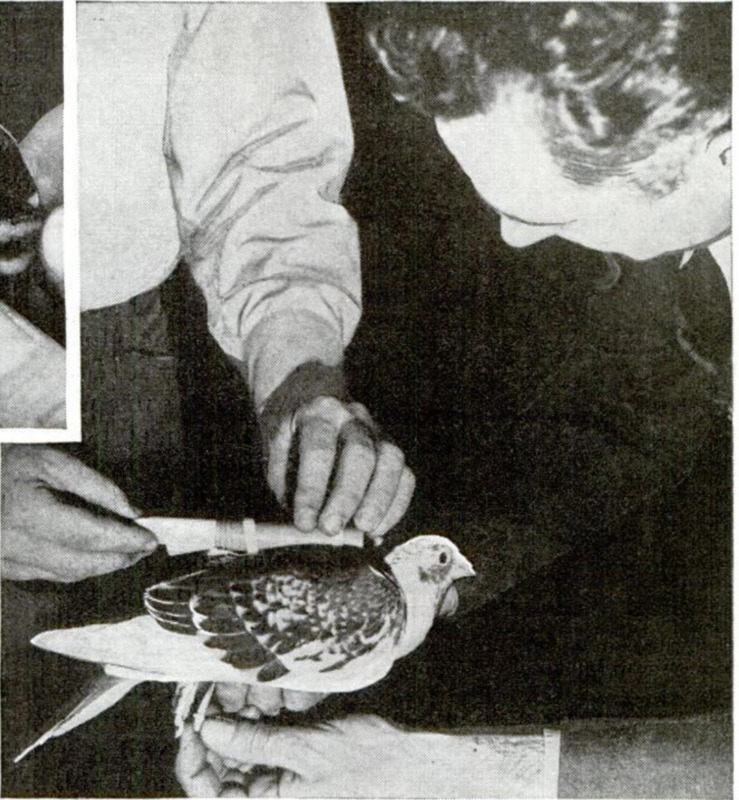

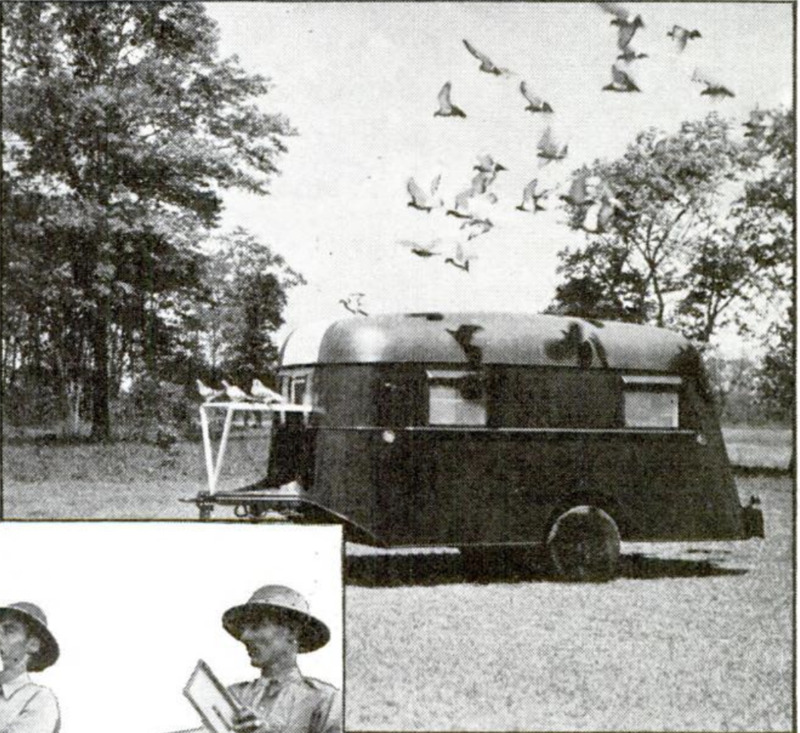

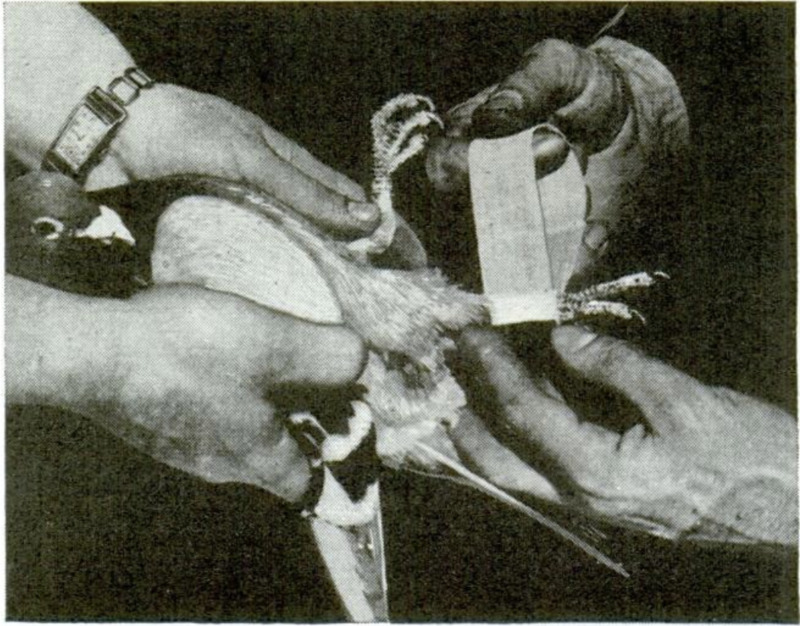

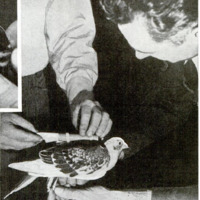

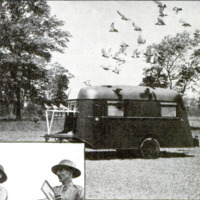

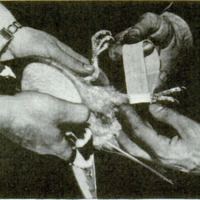

FROM the darkness surrounding the pigeon lofts at Fort Monmouth, N. J., a bell tinkles. An attendant hurries with a flashlight to remove from the leg capsule of a newly arrived bird a message highly important to the U. S. Army Signal Corps. It reveals that the pigeon was released sixty miles away less than two hours ago. In quick succession, six other pigeons swoop out of the night sky to the lofts, concluding the same trip. And the Signal Corps has completed another successful experiment in an almost revolutionary effort to develop night-flying birds. Pigeons have been used since ancient times as message carriers, but only in daylight hours, because it is unnatural for them to fly at night. Daytime use of pigeons has always been undesirable, from a military standpoint, because the birds frequently were brought down or wounded by enemy sharpshooters, and messages fell into the wrong hands or were lost. Too, pigeons were subject to attack by natural enemies, such as hawks, increasing the chances against messages reaching destination. Just recently the Signal Corps began trying to invert the habits and instincts of pigeons by training them to fly at night. One of the first discoveries was that not all pigeons are adaptable to this work, Hating night flying naturally, the average bird will not get into the air, but will land as soon as he sees an opening. Of course, birds that will not get into the air are never of value, for eventually they are certain to fly into wires or trees and injure themselves. Therefore, it has been necessary to select birds of superior intelligence and courage for night work. Long hours and plenty of patience are requisites for the trainer. Flying at night is a quality that may be developed in an individual pigeon, but it is not transmitted to the youngsters, so each bird must be trained. When the Signal Corps experiments began, the loft was brightly illuminated. Later, colored lights were tried and finally all lights were removed. The birds, it was found, fly as well to a dark loft as they did to one well lighted. Numerous attempts were necessary before the pigeons started returning to the loft from the point of release, a short distance away. Gradually the distance was increased until today the workable average is about twenty miles. However, the successful experiment covering nearly sixty miles is regarded as evidence that the birds soon will be able to fly reasonably long distances without becoming lost or injuring themselves. On that, the longest night flight attempted, the pigeons were released at 11:55 p.m., on a dark night, in a slight drizzle of rain. Another discovery made during the Signal Corps experiments is that the birds, because they do not like to fly at night, even though they have had years of training, always fly much faster than they would during the day. As a result, it is not uncommon to get speeds far in excess of a mile a minute at night. Average daylight speed is about thirty-five miles per hour, although speeds about twice that have been recorded under favorable conditions. Training methods have changed greatly in the past few years. Where previously the birds were controlled by use of their instinctive return to the mate, and by starvation - forcing them to return to the loft for food - now they are trained through kindness. Believing that the homing pigeon was intelligent enough to do anything required of it, if it were shown what was wanted, a training method was inaugurated to make the bird perfectly contented in the loft and to impress on it what was expected of it outside the loft. Results have been surprising. It is now possible to move a loft mounted on wheels into new positions, many miles away, and break the birds to a new location within twenty-four hours without having any of them fly back to the old location. It takes little imagination to recognize the value of this training to an army in the field. In the Fort Monmouth lofts 500 of the finest pigeons in the United States are housed. Here are bred replacement stock for the other army lofts and for the mobile lofts. When the youngsters are six days old a seamless metal band is placed on their legs. This band shows where the bird belongs, when it was hatched and gives the bird a permanent serial number. Young birds are taken from their parents when four weeks old and placed in lofts by themselves. Their first training consists of being placed on the loft landing board for a look at the country. As the birds grow stronger, they are taken from the loft, starting at only a few feet, and forced to fly back. At this time they are also trained to enter the loft when called. This is done by repeating a sound at feeding time until the birds associate that sound with “mess call” and will dash into the loft whenever they hear it. Later the pigeons are equipped with leg or back capsule. All are trained to carry these tiny tubes so that they will not fight them when taken into the field for use. The tube on the leg is very light and the messages are written on thin paper so there is very little weight. The back capsule, designed for carrying maps and photographs, is held in place by a harness. Each bird has to be fitted for this harness, to insure that it will fit properly and that the capsule is balanced on the bird’s back. Loads of as much as three ounces have been carried successfully in this manner.The mobile loft, converted from a standard house trailer, becomes the permanent home of the birds placed in it. They are allowed to mate and breed in this loft. It is. moved by being attached to a truck and towed. During preliminary training the loft is moved every day so that the birds become accustomed to looking for it, and no difficulty is experienced in making short moves while the birds are away from the loft, or in settling them in an entirely new location. On one occasion a loft was moved from Fort Monmouth to Cleveland, Ohio, and all birds flown to the loft within twenty-four hours after arriving. Probably the most famous pigeon in U.S. Army history was “Cher Ami,” which, according to records, carried the message that saved the Lost Battalion in the World War. When the bird reached its loft it was found that one leg was shattered and a machine-gun bullet had pierced its breast. The bird has been mounted and is now preserved in the National Museum. Another World War pigeon, captured from the German army in 1918, still lives in the Fort Monmouth lofts. Twenty-three years old, it is the last living World War bird. Just what causes the homing pigeon toreturn to its loft from distances as great as. 1,000 miles? Experts say that it is the homing instinct, the result of certain faculties, partly innate, partly acquired, which have been developed, modified and exploited by man for practical purposes. This is the instinct of orientation, which has been the subject of contradictory explanations. The remarkable improvements in the race since 1914, by means of intensive training, have undoubtedly proved that it cannot be explained as some special, mysterious and unchanging instinct, but as greater acuteness of certain senses and faculties. The ensemble of the bird’s intellectual faculties constitutes its intelligence. The principal faculties manifested by the pigeon’s return are attention, observation, memory, will sense of direction and physical fitness. The ear seems to play an important part in the pigeon’s sense of direction. It is regarded as possible that the sensitiveness of certain parts of the inner ear enables the bird to perceive magnetic and atmospheric impressions, A mature pigeon, if properly trained and in good health, is capable of covering dis- tances up to 600 miles in a single day. However, weather conditions are an im- portant factor and absolute reliability can- not be expected for distances over 200 miles. Normal military requirements for use within divisions generally range from three to twenty-five miles.

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1940-08

-

pagine

-

248-251, 127A

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Enrico Saonara

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)