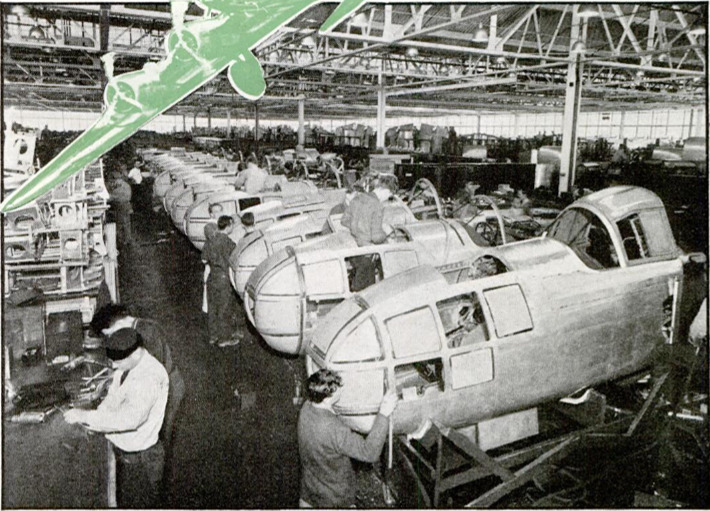

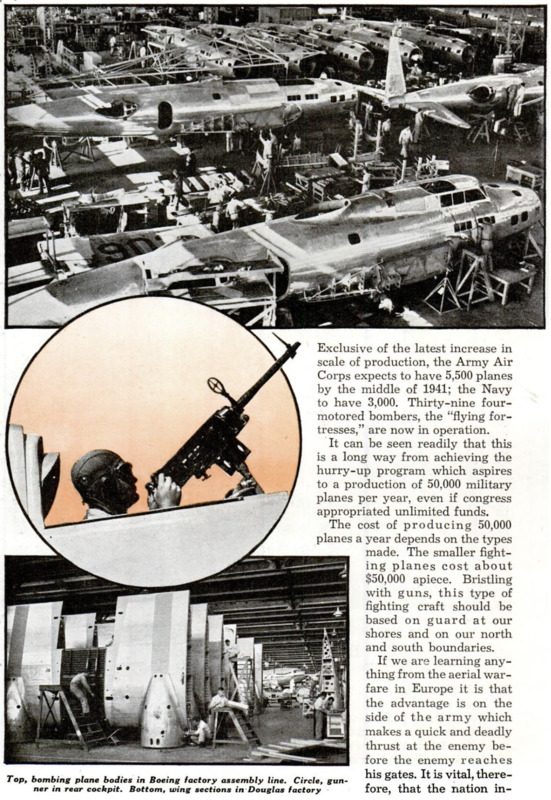

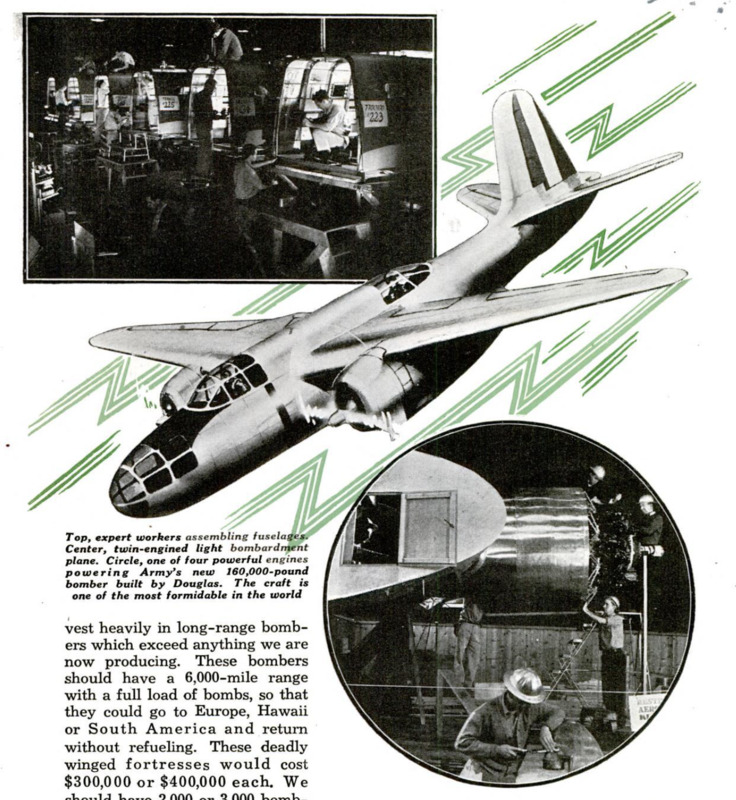

YANKEE ingenuity and talent for large-scale production should attain the goal of 50,000 fighting planes a year, in keeping with a program advanced by the government. ButI do not see how even the genius of the American industrialist can reach this mark until the end of 1942, still more than two years away - and then only at anestimated cost of more than six billion dollars for the first 50,000 planes. According to official government reports, America had 31,264 private and commercial pilots of all classes on January 1, 1940. A total of 13,772 planes of all types (except military) were certificated and in use. The Navy had 2,863 planes and the Army 2,700. Exclusive of the latest increase in scale of production, the Army Air Corps expects to have 5,500 planes by the middle of 1941; the Navy to have 3,000, Thirty-nine four-motored bombers, the “flying fortresses,” are now in operation. It can be seen readily that this is a long way from achieving the hurry-up program which aspires to a production of 50,000 military planes per year, even if congress appropriated unlimited funds. The cost of producing 50,000 planes a year depends on the types made. The smaller fighting planes cost about $50,000 apiece. Bristling with guns, this type of fighting craft should be based on guard at our shores and on our north and south boundaries. If we are learning anything from the aerial warfare in Europe it is that the advantage is on the side of the army which makes a quick and deadly thrust at the enemy before the enemy reaches his gates. It is vital, therefore, that the nation invest heavily in long-range bombers which exceed anything we are now producing. These bombers should have a 6,000-mile range with a full load of bombs, so that they could go to Europe, Hawaii or South America and return without refueling. These deadly winged fortresses would cost $300,000 or $400,000 each, We should have 2,000 or 3,000 bombers of this type. The United States should establish master air bases in New York, Miami, Brownsville, Tex., (on the international border) San Diego, Panama, Portland, Me., Alaska and at other points. From these bases lightning thrusts into the heart of the enemy would spend his power long before he arrived within striking distance of ourshores. The problem of selecting types of fighting craft for an adequate air arm, and the industrial problem of producing these craft - America’s vast and efficient system of manufacturing being what it is - is as nothing compared with the problem of training flying and maintenance personnel. For the task of training this personnel today is totally different from the training problem we faced in 1917-1918. At the end of the World War the Spad was the fastest plane on the western front. It had a speed of 130 miles per hour and 220 horsepower. Today, the speed is 400 miles per hour and the horsepower 1,200 or more on the latest models. My wartime Spad had two 30-30 machine guns. Today's Spitfires and Messerschmitts have eight guns. One pursuit ship today is a literal flying barrage. Then, from forty to fifty hours was supposed to qualify a pilot for combat over the lines. The simplicity of the fighting plane of twenty-five years ago has given way today to a complexity that is enormous. Today’s fighting pilot has to be an expert and a scientist because he is either flying a meteor or a monster, a fighting plane that streaks along at 300 to 400 miles per hour or a huge bomber like our flying fortresses. A man must have at least 750 hours of flight training before he is qualified to begin on bombers and it takes one year to produce a pursuit pilot. Here the problem assumes gigantic proportions. Let us estimate that10,000 of the 50,000 planes planned for production go to the Navy. At least 20,000 pilots will be needed for these planes. Peak efficiency demands that we have three pilots for every plane. In the Navy an operating crew of between twenty and forty men is needed for each plane, depending on its type. If we take thirty as an average crew, this means that a trained personnel of 300,000 mechanics will be needed by the Navy alone. In addition, the aircraft factories will need a minimum of 250,000 more trained men to produce these planes. Translate these figures into the Army’s task of training pilots to fly and mechanics to maintain 40,000 planes, and you have some idea of the magnitude of the job facing the nation if this vast program is to be achieved. The snail’s pace of 200 pilots emerging every six weeks from the advanced Army training school and 100 from the Navy school every month, will have to be stepped up miraculously if America’s fighting arm is to become the threat to the potential invader that is desired. There are important considerations to be given the relation between the production of aircraft and the training of men expected to fly and maintain them. One aspect of the problem cannot be studied intelligently without giving equal consideration to the other. For example, it would not be smart to produce large numbers of planes which would become obsolete by the time enough men could be trained to fly them. Modern combat planes become valueless in two years. It is important, therefore, not to let assembly-line production become a Frankenstein to the program as a whole. We know of only one way to train a pilot: that is, teach him how to fly and keep him flying. Any civilian effort such as the proposed “Plattsburg” flight training bases, must be closely synchronized with the real objective of shaping, ultimately, the student pilot into a well-trained military flier. It is well to remember that replacement facilities - both of men and machines - is the real key to supremacy in the air. The only thing that can really beat off an airplane attack is a better airplane. Germany has exceeded us in quantity of planes and pilots through a program of government ownership of all aircraft and compulsory military service. The United States is not ready to stand for either of these things. Our problem is to get ahead of them without government ownership of aircraft and without compulsory military service. I think it's a problem we can solve. In Germany, every youngster starts his study of aviation at the age of ten. In America, a few months ago, only 500 out of 26,000 high schools had any aviation activities. Let’s teach aviation in our schools and in our everyday life. Let’s carry by air all first-class mail dispatched distances of 100 miles or more. Let’s use the vast facilities already built up in our commercial air lines, to make us into an air-conscious and air-skilled people. Let’s use these strategic factors that no other nation in the world can equal, to develop more airplanes and more pilots, more maintenance personnel. Consider what this one step would do. At no cost to the government, our peacetime aviation industry would be increased 200 times, - not 200 per cent - 200 times. The aviation industry would jump at the chance to carry mail at the existing threecent rate. By thus expanding the peaceful work of aviation, pilots and technicians wouldspring up as a natural consequence of supply and demand. It would gear industry to a steady, to-be-counted-upon production. This policy would make aviation a mass industry that would absorb millions of young men eager to get into it. This program would give work for a peacetime air “army” but withal an “army” so formidable in numbers and so experienced in theair, that it would give any enemy pause. This is not the first time the United States has been faced with the necessity of arming quickly. All of the discussions now current are strongly reminiscent of 1917-1918 when America hurried into a well-meant but ill-considered air offense training and construction program which cost $750,000,000 and resulted in the construction of 18,000 fighting planes - all of them 50 obsolete that no plane of American design was in combat on the western front at the end of hostilities in November, 1918.