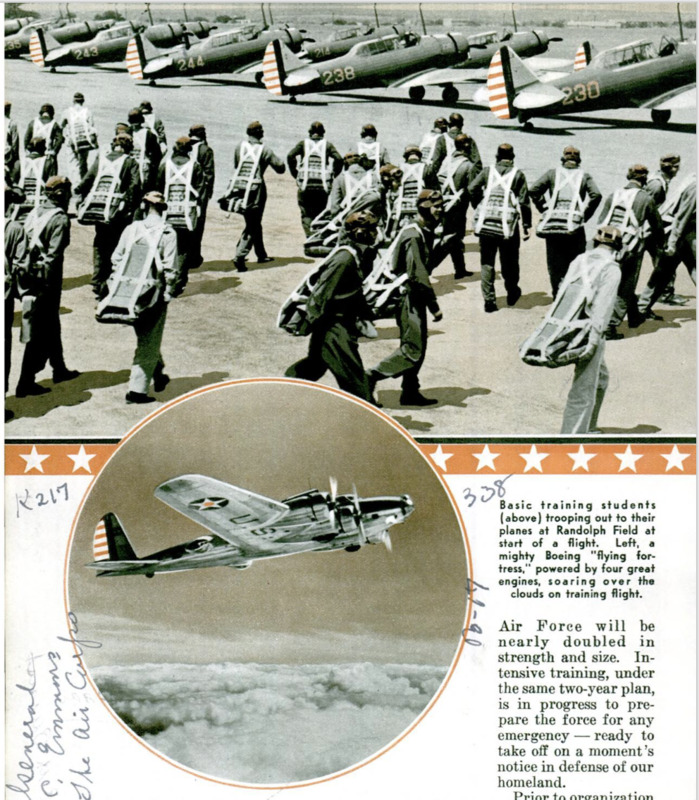

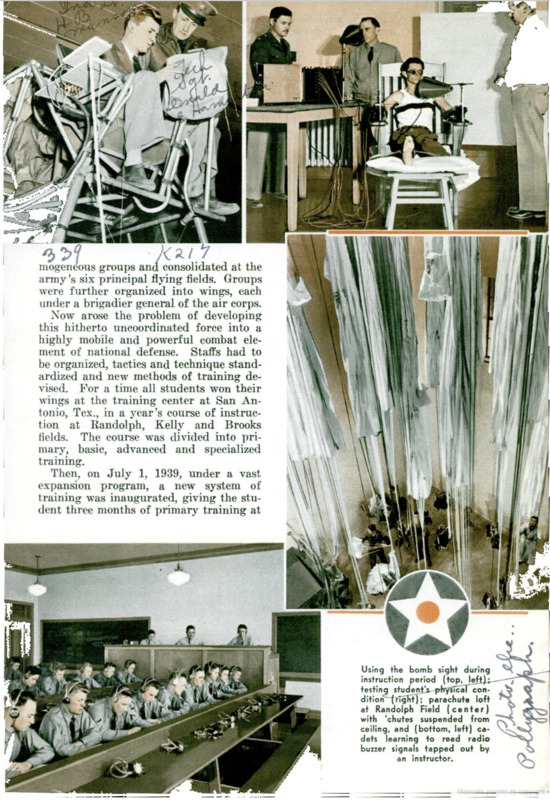

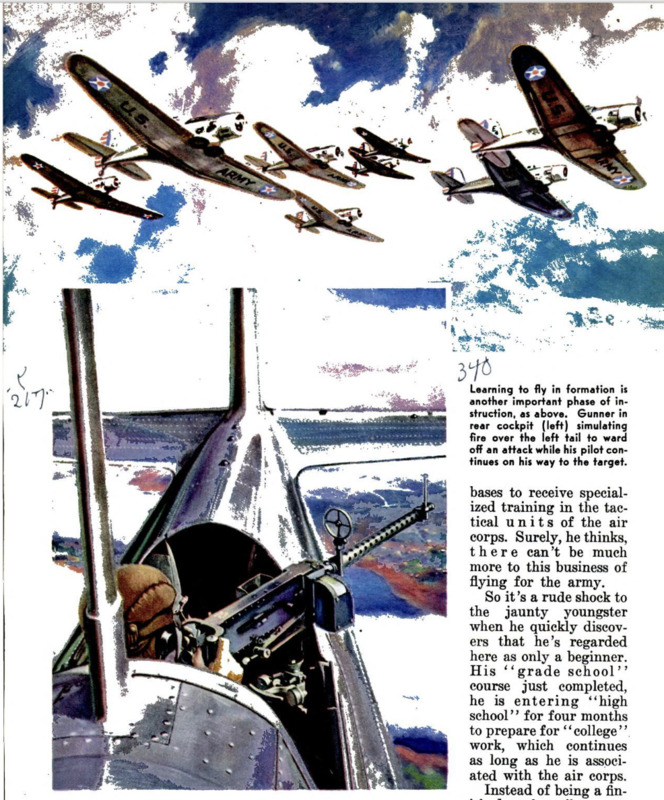

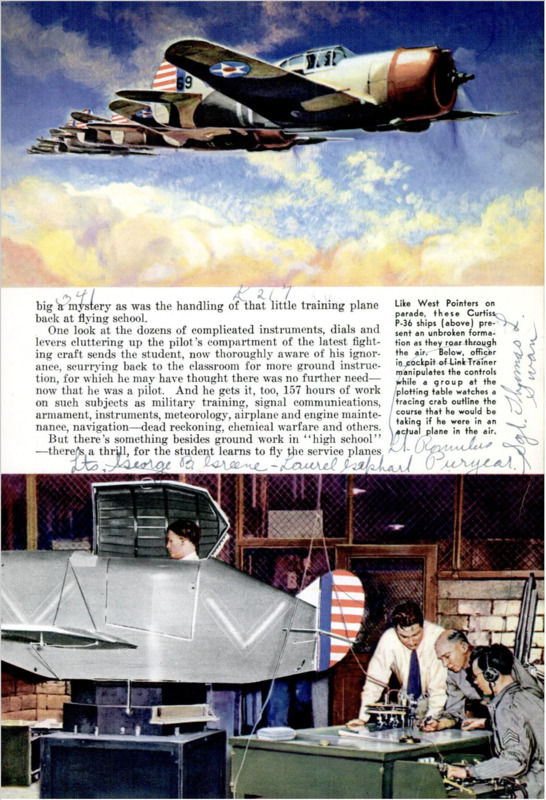

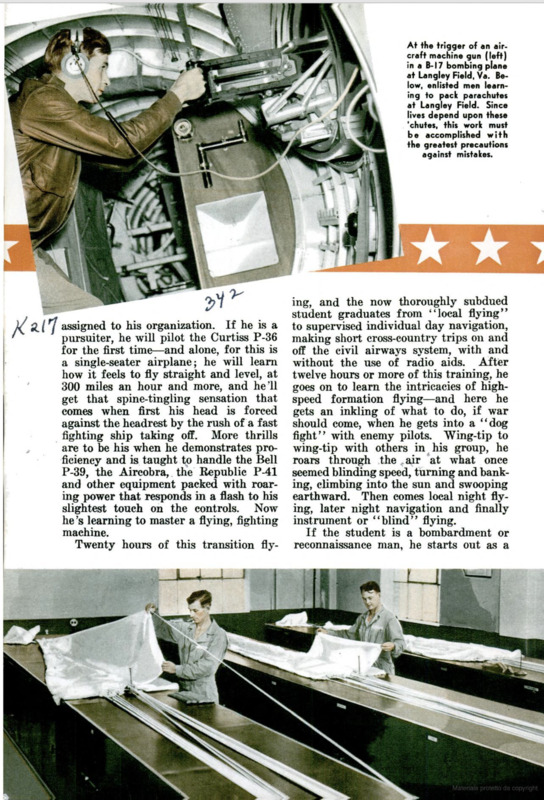

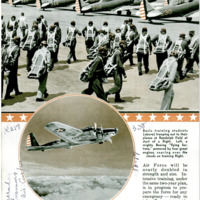

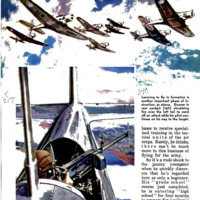

REORGANIZED into a streamline unit, General Headquarters Air Force, U. S. Army aviators have been launched upon a program of fly, bomb and shoot, without regard for weather, season or darkness. Increase in strength from an original twenty-nine squadrons to forty-five, and in personnel from skeletonized organizations to full man-power is under way, so that at the end of two years the GHQ Air Force will be nearly doubled instrength and size. Intensive training, under the same two-year plan, is in progress to prepare the force for any emergency - ready to take off on a moment’s notice in defense of our homeland. Prior to organization of this force, the training and development of military aviation were charged to the various corps area commanders. Coordination of training methods and objectives was difficult, with the result that each air unit had its own peculiar way of doing things. Finally, congress created GHQ Air Foree, placing all combat aviation under one command, and attack, bombardment and pursuit squadrons were immediately formed into homogeneous groups and consolidated at the army’s six principal flying fields. Groups were further organized into wings, each under a brigadier general of the air corps. Now arose the problem of developing this hitherto uncoordinated force into a highly mobile and powerful combat element of national defense. Staffs had to be organized, tactics and technique standardized and new methods of training devised. For a time all students won their wings at the training center at San Antonio, Tex., in a year’s course of instruction at Randolph, Kelly and Brooks fields. The course was divided into primary, basic, advanced and specialized training. Then, on July 1, 1939, under a vast expansion program, a new system of training was inaugurated, giving the student three months of primary training at civilian-operated, army-controlled flying sehools, three months of basic training at Randolph Field and three months of advanced training at Kelly and Brooks fields. Proud of his ‘‘wings’’ the student then reports for duty, perhaps with just a trace of cockiness, at one of the Air Force bases to receive specialized training in the tatical units of the air corps. Surely, he thinks, there can’t be much more to this business of flying for the army. So it’s a rude shock to the jaunty youngster when he quickly discovers that he’s regarded here as only a beginner. His ‘‘grade school’’ course just completed, he is entering ‘‘high school” for four months to prepare for ‘‘college’” work, which continues as long as he is associated with the air corps. Instead of being a finished combat pilot, as he may have fancied himself after handling the old-type planes at Kelly Field, he is merely ready to take transition training on the modern, high-speed equipment with which GHQ bases are being provided. He finds that piloting a 300-mile-an-hour pursuit ship or a giant four-engined bomber is almost as big a mystery as was the handling of that little training plane back at flying school. One look at the dozens of complicated instruments, dials and levers eluttering up the pilot’s compartment of the latest fighting craft sends the student, now thoroughly aware of his ignorance, scurrying back to the classroom for more ground instruction, for which he may have thought there was no further need - now that he was a pilot. And he gets it, too, 157 hours of work on such subjects as military training, signal communications, armament, instruments, meteorology, airplanc and engine maintenance, navigation - dead reckoning, chemical warfare and others. But there’s something besides ground work in ‘‘high school - therefs a thrill, for the student learns to fly the service planes assigned to his organization. If he is a pursuiter, he will pilot the Curtiss P-36 for the first time - and alone, for this is a single-seater airplane; he will learn how it feels to fly straight and level, at 300 miles an hour and more, and he’ll get that spine-tingling sensation that comes when first his head is forced against the headrest by the rush of a fast fighting ship taking off. More thrills are to be his when he demonstrates proficieney and is taught to handle the Bell P-39, the Aircobra, the Republic P-41 and other equipment packed with roaring power that responds in a flash to his slightest touch on the controls. Now he’s learning to master a flying, fighting machine. Twenty hours of this transition flying, and the now thoroughly subdued student graduates from ‘‘local flying” to supervised individual day navigation, making short cross-country trips on and off the civil airways system, with and without the use of radio aids. After twelve hours or more of this training, he goes on to learn the intricacies of highspeed formation flying - and here he gets an inkling of what to do, if war should come, when he gets into a ‘‘dog fight” with enemy pilots. Wing-tip to wing-tip with others in his group, he roars through the air ‘at what once seemed blinding speed, turning and banking, elimbing into the sun and swooping earthward. Then comes local night flying, later night navigation and finally instrument or ‘‘blind”’ flying.If the student is a bombardment or reconnaissance man, he starts out as a co-pilot on a Douglas B-18 or a Boeing four-engine “flying fortress’” and learns to play his highly essential part on the team that is | prosaically called the combat crew. He learns to take off and land these huge ships and to know the significance of the dozens of dials and levers that appeared so confusing upon his arrival, Of the specialized instruction, significant is the fact that this training begins a lifetime of such activity. The necessity for high proficiency in art that has become complicated and techgage the Air Force pilot in time of war. The pursuiter continues his work on a broader scale and progresses to acrobatics, aerial combat and gumnery, in which he continues to perfeet himself by constant daily practice as long as he is assigned to a tactical unit. The bombardment and reconmnaissance flier “grows up’’ to be a first pilot and along the way learns to be an expert aerial navigator, both celestial and dead reckoning. He also becomes proficient in the use of the flexible machine gun, the radio, the aerial camera and, of course, the all-important bomb sight. He has begun to learn how to “fly, bomb and shoot.” Perhaps more spectacular than the development of our tactical organization has been recent progress in the performance of military aircraft. The specifications of the first Wright airplane required, among other things, that “it carry two persons, remain aloft for a period of at least sixty minutes and have a speed of forty miles per hour in the still air.”At the beginning of the World War, speeds of 100 miles per hour in level flight were yet to be reached. For many years afterward the top speed of service equipment hovered around 150 miles an hour. But about eight years ago the development of the monoplane design began and with it the performance of military aircraft increased by leaps and bounds. Present types of pursuit planes are capable of speeds in excess of 300 miles per hour. Not so long ago the first of a new lot of Boeing “flying fortresses” crossed the continent non-stop at an average rate of 268 miles per hour to establish a new world’s record for military aircraft. All service planes are now capable of operat- ing at altitudes hitherto deemed impracticable, and the development of the first pressure-cabin stratosphere plane has passed the experimental stage. Today there are being manufactured for use in the GHQ Air Force, pursuit and bombardment airplanes that far surpass the performance of existing service equipment in speed, altitude, range and load characteristics. Even now the army is experimenting with a seventy-ton super-bomber. What tomorrow will bring in the way of fast, huge m% high-flying military airplanes is difficult to foresee. Five years ago night flying played but a small part in the routine training of the average officer. Non-stop flights of over, 500 miles were rare, and flights under adverse weather conditions were so fraught with hazard as to be considered prohibitively dangerous. Bombing and machine gun training was a brief seasonal affair, rel sulting in rather low standards of profidancy. Since inauguration of the “fly, bomb and shoot” program, instrument flying and night flying have been emphasized, with, the result that the combat efficiency of the Air Force has so improved that units are able to operate in almost any kind of weather, night or day. Thus today we have a highly trained force of experts admirably qualified to supervise the training of the hundreds of young men who will come into the expanding air corps. To provide strategically located bases from which to operate this enlarged GHQ Air Force, several new air bases are being established throughout the country. Upon, completion of the two-year plan the headquarters will be centrally located at Sco Field, Ill. To the First Wing will be added new base at McChord Field in Washington. The Second Wing will be increased by another base at Chicopee, Mass., and the Third Wing by the Southeast Air Base at Tampa, Fla. Up to now the First Wing had three bases, March Field, Hamilton Field and Moffett Field, all in California; the Second Wing, with headquarters at Langley Field, Va, had other bases at Mitchel Field, N. Y., and Selfridge Field, Mich., and the Third Wing had its base at Barks- dale Field, La. Completion of this air expansion program will provide the United States with an air force organized, trained and equipped to take its place, along with land and sea forces of the nation, in defending American soil against foreign aggression.