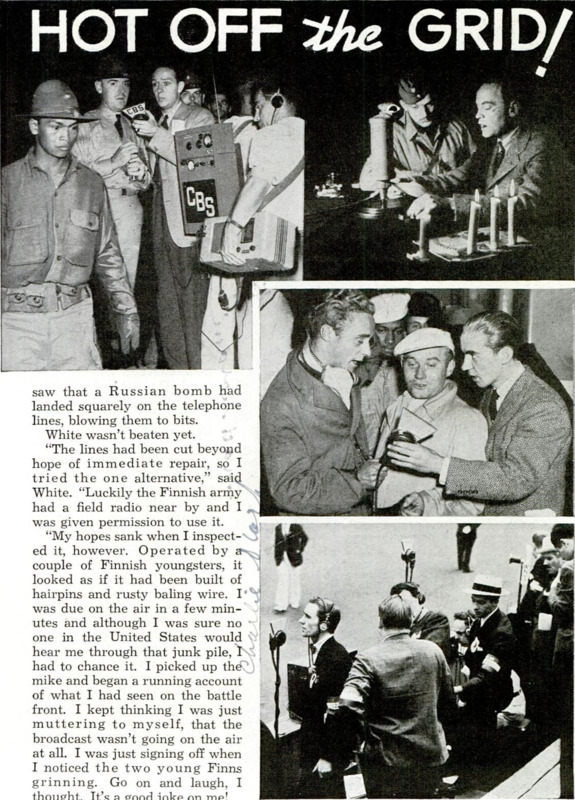

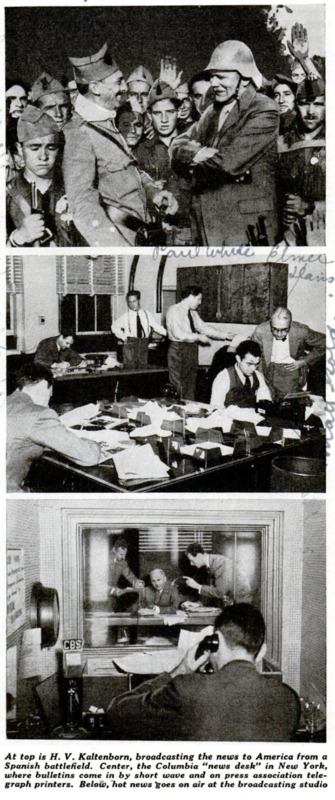

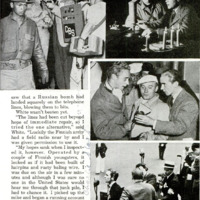

HEADED toward Viipuri, the big Russian bomber began unloading its cargo of death. William L. White, Columbia Broadcasting System's newscaster, stood knee-deep-in Snow in the woods with a score of Finnish villagers, watching the bombs descend. There was a terrific crash and the ground quaked with the explosion. White glanced at his watch. In a quarter of an hour, bombs or no bombs, he was to talk into a microphone hooked up to a telephone wire in a village near Viipuri. His on-the-spot account of fighting on the Finnish front, radio’s newest development in the broadcasting of hot news as it occurred, would be carried over that wire to Helsinki; thence to Stockholm, Berlin and Geneva, then shot across the Atlantic by short wave to Columbia Broadcasting System in New York. There radio engineers were waiting to put it on the air to the world. It was an intricate and effective hookup which modern science had worked out. But as White left the scant protection of the woods, he saw that a Russian bomb had landed squarely on the telephone lines, blowing them to bits. White wasn’t beaten yet. “The lines had been cut beyond hope of immediate repair, so I tried the one alternative,” said White. “Luckily the Finnish army had a field radio near by and I was given permission to use it. “My hopes sank when I inspected it, however. Operated by a couple of Finnish youngsters, it looked as if it had been built of hairpins and rusty baling wire. I was due on the air in a few minutes and although I was sure no one in the United States would hear me through that junk pile, I had to chance it. I picked up the mike and began a running account of what I had seen on the battle front. I kept thinking I was just muttering to myself, that the broadcast wasn’t going on the air at all. T was just signing off when I noticed the two young Finns grinning. Go on and laugh, I thought. It’s a good joke on me! “Then one of them took off his headset and told me that New York had just reported one of the best receptions it had ever had from Finland.” While the broadcasting of news has been familiar to radio listeners for over a decade, on-the-spot broad- cast of news is a new and thrilling development hastened by the anxiety of American listeners over the war crises in Europe. Previous to 1929 newscasters could go just as far afield as the end of the telephone line. Outstanding news events could only be covered if telephone lines were extended in advance; that didn’t allow for broadcasting “hot” newsjustasitoccurred. So science got busy to develop mobile units - trucks equipped with short-wave sets, pack sets and still smaller sets which could be installed in the newscaster’s wearing apparel. One set had a wrist-watch microphone, a walking-stick antenna and transmitter and batteries in a binocular case. Such devices were all right for broadcasting in America where there were many facilities obtainable. Transatlantic broadcasting was another matter. Already events in Europe were making that type of newscasting vital, and H. V. Kaltenborn, news analyst, had put on a news broadcast from Spain in 1936 which caused American radio listeners to demand more. He took microphone and equipment to the farmland outside Irun and described the Nationalist attack on that Loyalist stronghold. His talk was punctuated with the boom of cannon and the rattle of machine guns. He was the first man to broadcast directly from the battlefield. Closeted with technicians in the Columbia offices in New York, Paul White, Director of Public Affairs, took stock of the war cloud last August. Details of high-speed coverage of on-the-spot news were worked out. Censorship and other conditions incidental to war were carefully considered. “During the Austrian Anschluss we realized that in crises European governments would clamp censorship on broadcasters as well as on newspapermen,” said Mr. White. “The most effective antidote would be simultaneous pick-ups from several capitals. Listeners could thus hear several points of view on the same program.” It was also necessary to keep the various reporters in Europe informed of events elsewhere. The engineers worked out a four-way transatlantic radiotelephone channel which enabled reporters in London and Paris to listen in and talk to New York and Washington just as if the four were sitting together in one room. The four cities were connected by a continuous loop of telephonic short-wave and land-line facilities. The technicians were faced with a tough nut to crack in eliminating the voice of the speaker in his own earphones. If this hadn’t been done, there would have been a feedback of two-fifths of a second, enough to create an impossible mixture of double talk on the air. “Cue channels” on direct short wave between New York, London and Paris, Berlin and Rome are always available. Over these, first the traffic men, then Paul White, speak for five minutes before each news program - the traffic men to check ship “Altmark” on the air in a thrilling interview which gave the first details of how the British had driven the “Altmark” ashore and rescued the seamen confined aboard. Somehow, despite the obstacles of censorship, red tape and the hazards of war conditions, the newscasters manage to meet their radio deadlines and broadcast red-hot news. Miss Breckinridge tells of traveling “by plane, train, boat, tug, bicycle, bus, ice skates, taxi, horse, cab and shanks’ mare,” broadeasting from “a London sub-basement, the attic of a post office in Dublin, a small house in Stavanger, a derelict, unfinished building in the fortified zone in Berlin.” All the newscasters are confronted with the problem of censorship, some of which doesn’t seem to make rhyme or reason. One unusual instance occurred when White was under fire at Viipuri. “A Russian long-range gun was dropping a shell into town nearly every forty seconds,” he said, “at such regular intervals that while trying to get from the hotel to the improvised studio where I was to broadcast, I could make thirty-second dashes and then seek cover before the next one landed. “When I went on the air a shell landed so near it jarred the microphone, Luckily it was a dud but I couldn’t tell the radio audience that. I started to, but the censors stopped me. Later they explained the Russians might be listening, and if they found their artillery was firing duds they’d do something mighty fast about substituting live shells.” Newscasters with censors beside them at the microphone have resorted to ingenious means to evade censorship. One is to put the banned news in American slang. Another is to accent certain words and hope the audience draws a true inference. The technique of modern newscasting has gone a long way. Radio engineers, technicians and the newscasters themselves are constantly devising new methods of getting hot news on the air. Whatever lies ahead, wherever the big stories break, the newscasters will speed to them despite all obstacles, and somehow put them on the air for radio listeners.

Popular Mechanics, v. 74, n. 3, 1940

Popular Mechanics, v. 74, n. 3, 1940