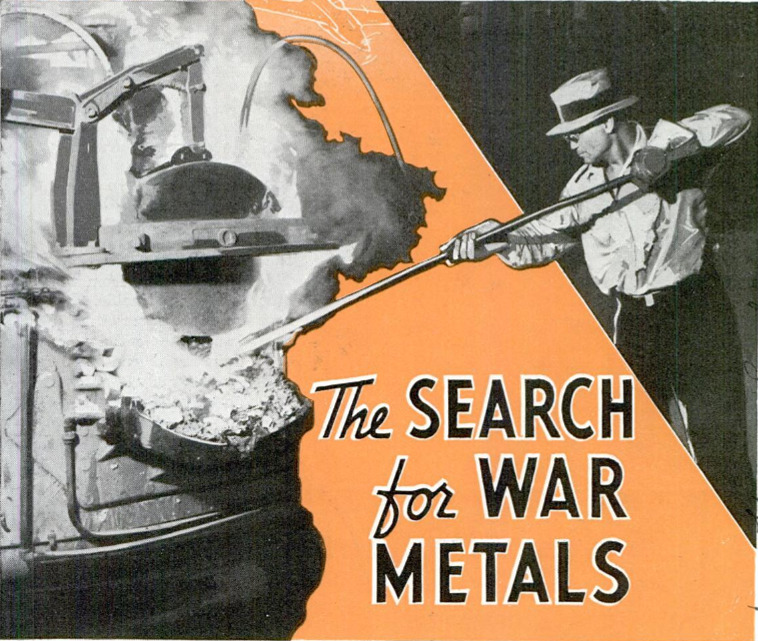

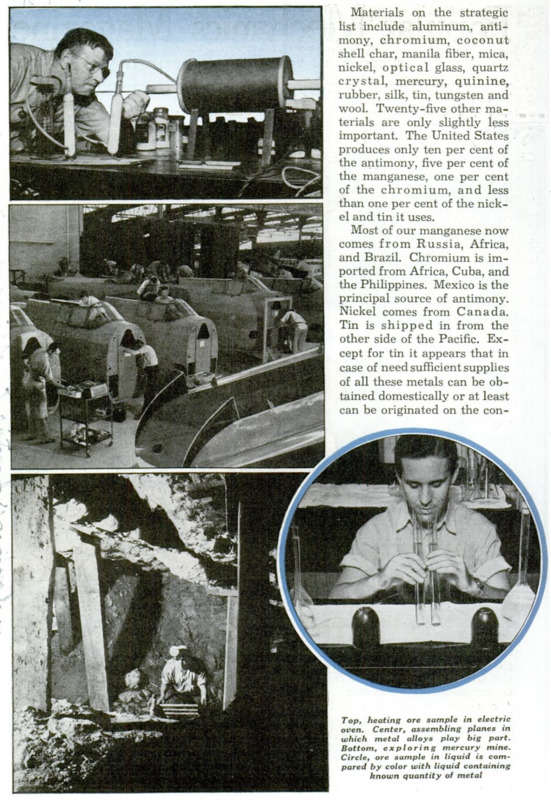

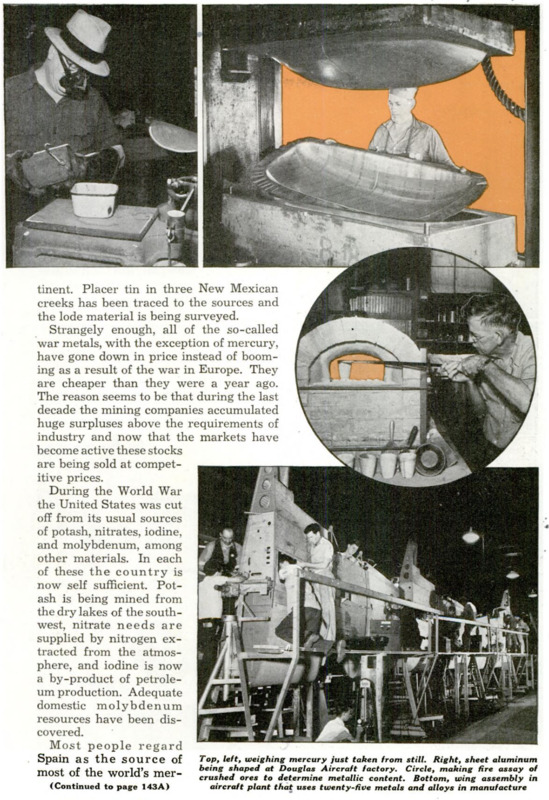

PROWLING through abandoned mines and sometimes building their own roads to reach inaccessible areas, 200 engineers of the U. S. Bureau of Mines the Geological Survey are investigating our supplies of vital minerals. The United States is the most self-sufficient country on earth yet it normally depends on foreign sources for most of the tin, antimony, nickel, manganese and some of the other materials required by industry. Some can be obtained cheaper abroad than here; in other cases our deposits are inadequate. If ordinary channels of trade were disrupted the country might be cut off from materials it has to have. To guard against this possibility the government is spending $10,000,000 as a starter to buy and store reserves of strategic metals. In addition a four-year search is being made to map out our own resources. Already it has been learned that the country is richer than had been supposed in manganese, chromite, tungsten, mercury, and antimony, minerals essential in peace and absolutely necessary in war. Materials on the strategic list include aluminum, antimony, chromium, coconut shell char, manila fiber, mica, nickel, optical glass, quartz crystal, mercury, quinine,rubber, silk, tin, tungsten and wool. Twenty-five other materials are only slightly less important. The United States produces only ten per cent of the antimony, five per cent of the manganese, one per cent of the chromium, and less than one per cent of the nickel and tin it uses, Most of our manganese now comes from Russia, Africa, and Brazil. Chromium is imported from Africa, Cuba, and the Philippines. Mexico is the principal source of antimony. Nickel comes from Canada. Tin is shipped in from the other side of the Pacific. Except for tin it appears that in case of need sufficient supplies of all these metals can be obtained domestically or at least can be originated on the continent. Placer tin in three New Mexican creeks has been traced to the sources and the lode material is being surveyed. Strangely enough, all of the so-called war metals, with the exception of mercury, have gone down in price instead of booming as a result of the war in Europe. They are cheaper than they were a year ago. The reason seems to be that during the last decade the mining companies accumulated huge surpluses above the requirements of industry and now that the markets have become active these stocks are being sold at competitive prices. During the World War the United States was cut off from its usual sources of potash, nitrates, iodine, and molybdenum, among other materials. In each of these the country is now self sufficient. Potash is being mined from the dry lakes of the southwest, nitrate needs are supplied by nitrogen extracted from the atmosphere, and iodine is now a by-product of petroleum production. Adequate domestic molybdenum resources have been discovered. Most people regard Spain as the source of most of the world’s mercury and are unaware that California, with fifty-nine mercury mines, is now fulfilling the domestic demand. Mercury is a vital war metal and now that its price has risen to $192 per seventy-six-pound flask from the average of $80 per flask earlier in the year many of the inactive California mines have resumed production. Instead of prospecting for new deposits, the engineers of the Bureau of Mines are simply estimating the reserves that may be available in the known mineralized areas. A large deposit of low-grade manganese, for instance, is an important national asset even though it can’t be mined profitably at present prices. Mining costs would be relatively unimportant in an emergency that cut off foreign shipments. The engineers are busy in several of the western states. One group may be rushing its work at 10,000 feet to complete its survey before snow falls, while another is fighting the heat on a desert expedition. Some travel by pack train while others use tractors. One hundred and sixty-two of the most promising mineral deposits have been given field examinations and of these thirty-three seemed promising enough to warrant more detailed study. Several hundred additional properties will be examined. In the hunt for antimony the engineers have explored two important areas in Idaho. Using tractors and bulldozers, the engineers built their own roads, stripped 3,000 cubic yards of earth from steep wooded hillsides, drove tunnels, and drilled into the formations to estimate their value. In eastern Oregon one party took time out to fight a forest fire before they finished examining a chromite deposit. In Wyoming 9,000 trees had to be removed so that tractors could trench the surface of another chromite deposit. In Nevada several tungsten deposits have been explored. Meanwhile prospectors who have been combing the west for gold and silver are turning their attention to the baser metals. A good ledge of tungsten or chromium ore may be worth more than a gold mine. Prospecting methods have changed and among other new developments is a kind of vacuum cleaner that collects heavy cuttings from holes drilled into underground formations. Such samples were formerly taken by slow, expensive core drilling. Geologists have known for a long time that vegetation is often an indication of mineralized zones and that changes in the type or coloring of surface plants may be associated with changes in the minerals below. Prospectors who use airplanes for general studies pay special attention to ground where long lines or islands of brush differ from surrounding vegetation. Vegetation is being analyzed for its mineral content as a way of learning whether commercial grades of ore may be found below the surface. Slight traces of many minerals are necessary parts of a healthy plant’s diet and a plant absorbs minerals to the extent that each is present in the soil or the water that sustains it. A large percentage of one element in a plant suggests that a deposit exists near by. A number of very necessary war metals, such as copper, lead, and zinc, are not regarded as strategic minerals because the United States already has tremendous quantities available. To maintain our supplies of copper one company is developing a huge body of low grade ore in Arizona. Known as the Clay ore body, it is a mile long, half a mile wide, and 800 feet deep. Half a million pounds of copper a day will be refined when the new mine is operating.

Popular Mechanics, v. 74, n. 4, 1940

Popular Mechanics, v. 74, n. 4, 1940