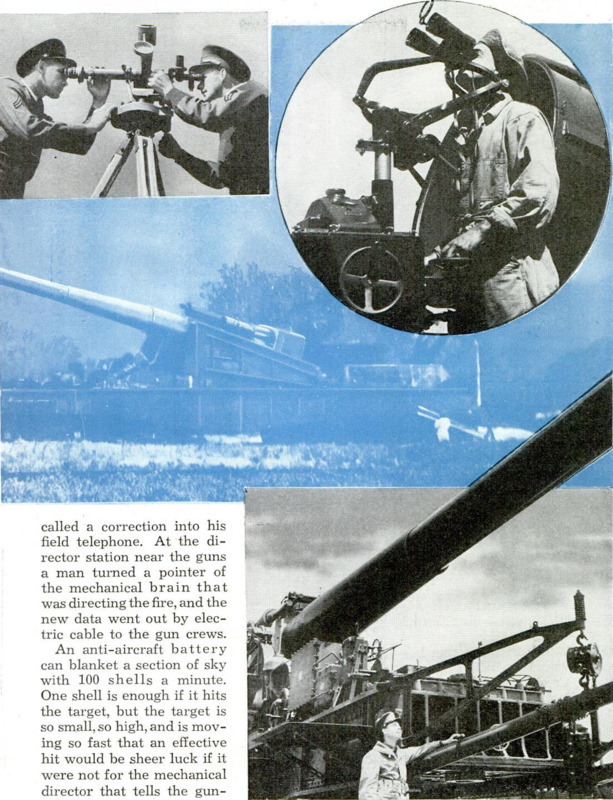

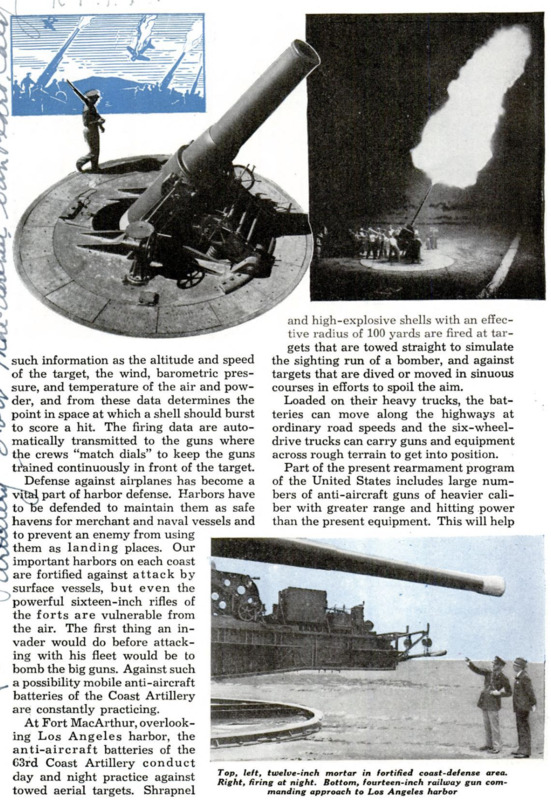

Modernizing Our Coast Defense

Contenuto

- Titolo

- Modernizing Our Coast Defense

- Article Title and/or Image Caption

- Modernizing Our Coast Defense

- Lingua

- eng

- Copertura temporale

- World War II

- Data di rilascio

- 1941-01

- pagine

- 72-75, 123A, 124A

- Diritti

- Public Domain (Google digitized)

- Sorgente

- Google books

- Referenzia

- Fort MacArthur

- Los Angeles

- United States of America

- Panama Canal

- Gibraltar

- San Francisco

- World War I

- Alaska

- Panama

- Archived by

- Enrico Saonara

- Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

- Copertura territoriale

- United States of America