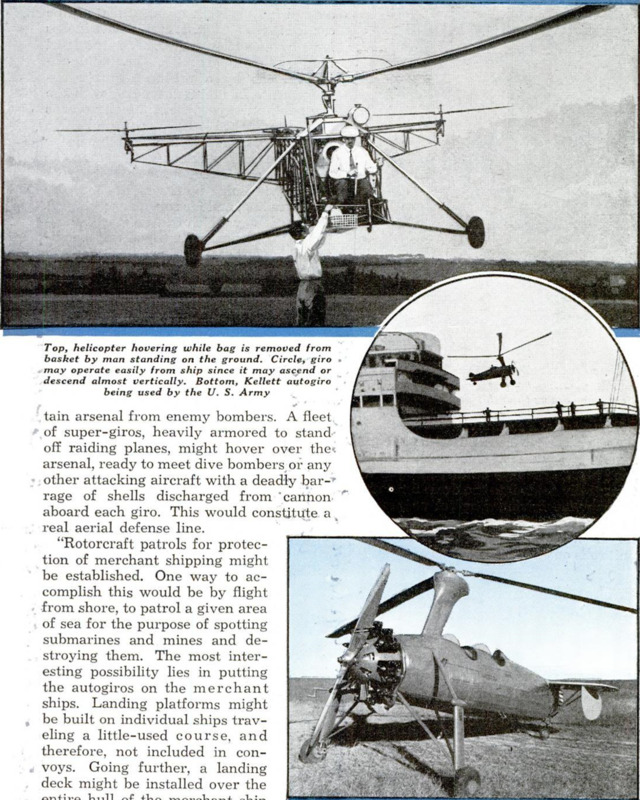

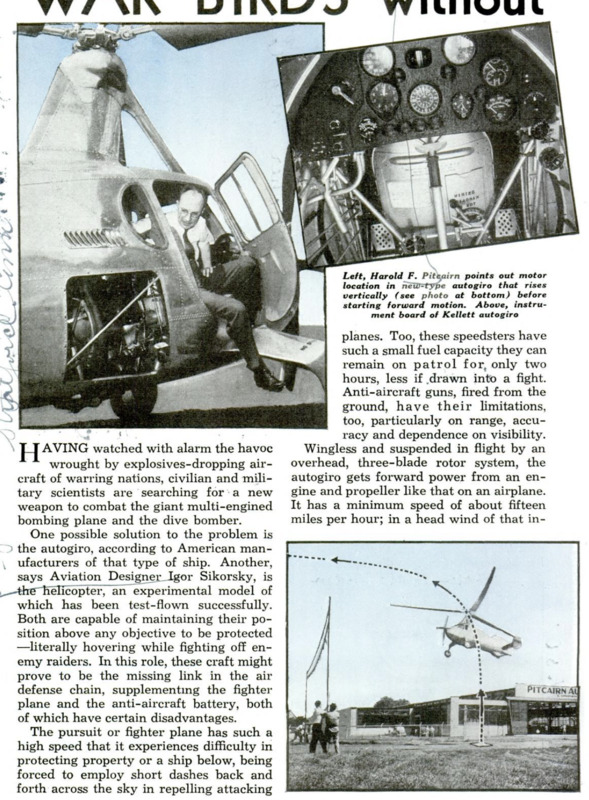

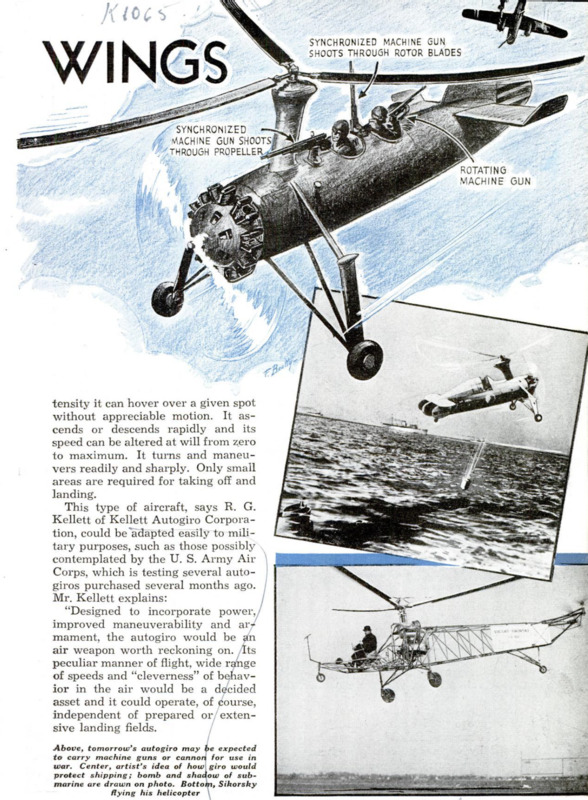

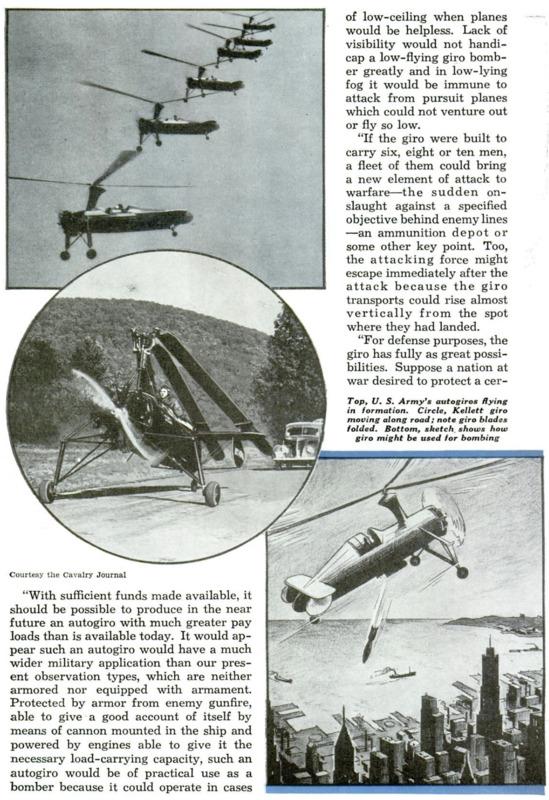

HAVING watched with alarm the havoc wrought by explosives-dropping air- craft of warring nations, civilian and military scientists are searching for a new weapon to combat the giant multi-engined bombing plane and the dive bomber. One possible solution to the problem is the autogiro, according to American manufacturers of that type of ship. Another, says Aviation Designer Igor Sikorsky, is the helicopter, an experimental model of which has been test-flown successfully. Both are capable of maintaining their position above any objective to be protected - literally hovering while fighting off enemy raiders. In this role, these craft might prove to be the missing link in the air defense chain, supplementing the fighter plane and the anti-aircraft battery, both of which have certain disadvantages. The pursuit or fighter plane has such a high speed that it experiences difficulty in protecting property or a ship below, being forced to employ short dashes back and forth across the sky in repelling attacking planes. Too, these speedsters have such a small fuel capacity they can remain on patrol for, only two hours, less if drawn into a fight. Anti-aircraft guns, fired from the ground, have their limitations, too, particularly on range, accuracy and dependence on visibility. Wingless and suspended in flight by an overhead, three-blade rotor system, the autogiro gets forward power from an engine and propeller like that on an airplane. It has a minimum speed of about fifteen miles per hour; in a head wind of that intensity it can hover over a given spot without appreciable motion. It ascends or descends rapidly and its speed can be altered at will from zero to maximum. It turns and maneuvers readily and sharply. Only small areas are required for taking off and landing. This type of aircraft, says R. G.Kellett of Kellett Autogiro Corporation, could be adapted easily to military purposes, such as those possibly contemplated by the U. S. Army Air Corps, which is testing several autogiros purchased several months ago. Mr. Kellett explains: “Designed to incorporate power improved maneuverability and armament, the autogiro would be an air weapon worth reckoning on. Its peculiar manner of flight, wide range of speeds and “cleverness” of behavior in the air would be a dgcided asset and it could operate, of dourse, independent of prepared or extensive landing fields. “With sufficient funds made available, it should be possible to produce in the near future an autogiro with much greater pay loads than is available today. It would appear such an autogiro would have a much wider military application than our present observation types, which are neither armored nor equipped with armament. Protected by armor from enemy gunfire, able to give a good account of itself by means of cannon mounted in the ship and powered by engines able to give it the necessary load-carrying capacity, such an autogiro would be of practical use as a bomber because it could operate in cases of low-ceiling when planes would be helpless. Lack of visibility would not handicap a low-flying giro bomber greatly and in low-lying fog it would be immune to attack from pursuit planes which could not venture out or fly so low. “If the giro were built to carry six, eight or ten men, a fleet of them could bring a new element of attack to warfare - the sudden onslaught against a specified objective behind enemy lines - an ammunition depot or some other key point. Too, the attacking force might escape immediately after the attack because the giro transports could rise almost vertically from the spot where they had landed. “For defense purposes, the giro has fully as great possibilities. Suppose a nation at war desired to protect a certain arsenal from enemy bombers. A fleet of super-giros, heavily armored to stand off raiding planes, might hover over the arsenal, ready to meet dive bombers or any other attacking aircraft with a deadly barrage of shells discharged from cannon aboard each giro. This would constitute a real aerial defense line. “Rotorcraft patrols for protection of merchant shipping might be established. One way to accomplish this would be by flight from shore, to patrol a given area of sea for the purpose of spotting submarines and mines and destroying them. The most interesting possibility lies in putting the autogiros on the merchant ships. Landing platforms might be built on individual ships traveling a little-used course, and therefore, not included in convoys. Going further, a landing deck might be installed over the entire hull of the merchant ship or tanker, thus converting such a vessel into a rotorcraft carrier which might thus become a means of protecting not only itself but other vessels in a convoy. Five to ten autogiros, equipped to fight off bombing planes, might be kept in the air at all times. Naturally adaptation of the giro to convoy protection would release surface ships, such as destroyers, for more important duties.” Following tests of the experimental helicopter which he designed. Mr, Sikorsky says it now appears possible to produce a two-seater helicopter powered with a 200 horsepower engine. Such a craft would be able to take off and land in small spaces, to travel forward at any speed between zero and slightly above 100 miles per hour, to move sideways or backward at velocities up to twenty-five miles per hour, to hang motionless in the air and to climb at better than 1,000 feet per minute. The Sikorsky helicopter has a single large lifting rotor, similar in some respects to the overhead rotor of the autogiro, and three small auxiliary rotors or propellers, supported by an outrigger. The main rotor furnishes most of the lift that supports the machine in flight. The change of the pitch of this rotor forms the basis of the control of the machine for up-and-down motion. Two of the auxiliary rotors that are situated on vertical shafts on both sides of the outrigger furnish means for longitudinal and lateral control. Varying the pitches of these propellers in the same direction produces longitudinal control; variation in the opposite direction gives lateral control. These control motions are connected to a pilot stick, giving an effect similar to the conventional airplane. A mechanism that varies the pitch of the rear propeller is connected with foot pedals and furnishes means for directional control. By operating the controls and engine throttle properly, the pilot can hold the helicopter at a given altitude or cause it to descend or to jump up momentarily. Thus the pilot is able to ascend or land exactly when he sees the right moment. In case of engine failure aloft, the rotors continue to turn automatically, permitting the machine to come to earth gently. Of the possibilities of this machine, Mr.Sikorsky says: “The airplane, by nature of its design, will always be faster than the helicopter - perhaps in the order of about five to three, or 500 miles an hour to 300 miles an hour in future designs. However, for defensive and special military purposes, the helicopter can do many things impossible to the airplane which make it of vital significance. For example, to interpose an effective defense against bombers or dive bombers, the helicopter seems to me to be ideal. It can stand still in the air, thus affording a stable gun emplacement from which the gunner can await the moment – which must come either in bombing from altitude or in dive bombing technique - when the bomber ceases all zigzag maneuvering and flies a perfectly straight line for its quarry. Then the bomber is comparatively easy to hit. The helicopter, of course, easily can have altitude performance up to 15,000 feet or more and can carry large caliber machine guns or even cannon. “The helicopter, in naval use, would require only a patform or deck space about forty feet square from which to take off and on which to land. It could follow every dodging movement of surface craft, flying backward, forward or sideways at will, and always itself afford a steady firing point for its guns defending a battleship. “Landing gear for the helicopter would be rubber bags rather than wheels. On these bags the machine could use land, water, ice, snow, a vessel or a building for a take-off o landing.” A Pitcairn-built autogiro, in a demonstration recently, exhibited an ability to make jump take-offs, rising vertically twenty feet or more, then pulling away in a normal climb. Thus, no run along the ground is necessary to attain flying speed, an advantage in operations in small spaces. Preparatory to the jump, through a hydraulic system, a single-control lever locks the wheel brakes, sets the rotor blades at zero pitch and engages the rotor clutch for power to the rotor, during which time the gear ratio within the transmission is set at two to one. Then the pilot advances the throttle and when full power is reached and the rotor is turning three hundred revolutions per minute, the mere pressing of a lever causes the machine to leave the ground, shooting straight upward. Thus independent of vast air fields for moving away from or coming to earth, as well as incorporating many other characteristics which aviation experts regard as highly desirable, the wingless aircraft seems on the verge of development into an important weapon of defensive - perhaps even offensive – warfare.

Popular Mechanics, v. 75, n. 2, 1941

Popular Mechanics, v. 75, n. 2, 1941