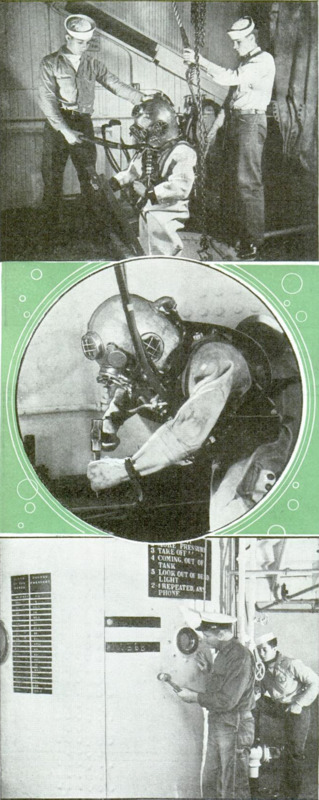

IF YOU think diving is a glamorous profession, visit the Navy’s Deep-Sea Diving School, at the Washington Navy Yard, and be disillusioned. Here, picked men are trained in the grim and hard business of rescuing sunken submarines, repairing ship bottoms, and doing a hundred and one specialized mechanical jobs on the bottom of the sea. With every man a potential hero, facing injury and death in his routine daily work, the idea of developing diving “prima donnas” is discouraged at the outset. Students are sent down to their underwater jobs strictly in rotation and for periods depending upon their strength and ability - just as they will be later sent down as regular divers of the navy. Candidates are volunteer boatswain’s mates, gunner’s mates, carpenter’s mates, torpedomen, or shipfitters, between the ages of twenty and thirty. They must be sound inbody and sober in temperament. A man with weak heart or lungs, or who gets excited easily, would never do for strenuous work fifty fathoms under the ocean. So much stamina is needed that no man in the navy is allowed to go down more than ninety feet, after he reaches forty years of age. Contrary to the general opinion of divers as big, husky, bruiser-type men, best diver material comes from men who are rather thin, muscular, and wiry. Prospects twelve per cent overweight are rejected, on the grounds that fatty tissue absorbs nitrogen faster than does muscular tissue, thus making fat men more susceptible to the “bends” than thin men. As diving dresses come in only three sizes, divers must also be between five and a half and six feet tall. Of the six months intensive training, one-fifth is spent in classrooms, studying pumps and air pressures, first aid and resuscitation, physics and mathematics of diving, and the theory of diving operations. The remainder is devoted to practical mechanical work that might be required in an emergency, and to actual diving. After a thorough physical examination, and before his first dive, a student is put into a recompression chamber where air pressure is built up to fifty pounds to the square inch. This is to determine if high air pressures can be equalized on both sides of the ear drums. If pain or nausea is experienced, the man must forget a career as diver. If he reacts normally, however, he then goes to the “topside” - the room above the diving tank - where fellow students help him into the cumbrous and grotesque gear which is the working clothes of his profession. As life may depend upon the proper adjustment of a valve, or the tightening of a nut, the job of dressing must be done with meticulous care. The diver first dons heavy, long-legged and sleeved woolen underclothing and woolen socks to keep him warm and to prevent the diving dress from chafing. In cold water, three outfits of woolens may be worn. Then comes the dress, made of fabric and rubber, which covers the body to the neck. The back of the legs are laced up to prevent the legs from becoming overinflated and toppling him over. Next come shoes, weighing seventeen and one-half pounds each; lead belt, eighty-three pounds; breastplate and helmet weighing fifty-four pounds. A heavy leather strap, buckled at both ends to the belt, is passed between the diver’s legs to keep the belt from sliding up and the helmet from rising above the head. Completely dressed, the diver-to-be clumps awkwardly to the ladder of the tank, weighted down with 200 pounds of canvas, rubber, bronze, and lead. Last-minute instructions given, a tender fastens the faceplate of the helmet, gives two taps on top of the “hat,” and the novice clambers down through the air lock into the steel tank which is to be his “classroom.” In this tank, student divers first learn to walk; then they learn to work. When a diver is sent down on a rescue job he must be able not only to maneuver in icy darkness, but perform difficult mechanical jobs. He must be able to measure holes accurately, chip off rivets, drill and saw steel plates, calk broken seams, attach flanges and pipe fittings, cut and weld with an electric torch. The men first learn these jobs at the workbench, then carry then out at successively greater depths to 300 feet. Although the water in the tank is only twelve feet deep, pressures equaling those encountered down to 300 feet are produced by pumping compressed air on top of the water. To keep the water from crushing the diver’s body, the pressure of the air which the diver breathes, and which fills his dress, must be even higher than that of the water - reaching, at 300 feet, nearly 200 pounds to the square inch, or a total of 200 tons on the man’s entire body! Thinking and movements become retarded as the diver goes deeper. At 300 feet simple tasks become so strenuous that the diver often gets “woozy,” fumbling about in a daze and claiming over his telephone that he is doing things which he is not. Sometimes a man goes unconscious. The reason is not definitely known, but it is thought that the nitrogen absorbed into the blood and tissues may not be as inert as generally supposed, but may have a chemical effect on the body. In good weather, diving students test their tank experience on the bottom of the Potomac river, where they learn to recover lost articles, repair wharf piling, inspect ship bottoms, and work hand pumps used in shallow diving. For deep work in the open sea, the school’s diving boat “Crilley” - named after Frank Crilley, who distinguished himself in the salvaging of the submarine F-4, off Honolulu in 1915 - stands out to a spot off Piney Point, Md., where men struggle for two or three weeks riging pontoons, and learning to maneuver a rescue chamber, such as was used in the heroic rescue of thirty-three men from the ill-fated “Squalus.” Smoking is permitted to diving students, but alcohol is strictly forbidden. If a man goes on a drinking spree, he must refrain from diving for at least forty-eight hours. Alcohol changes the heart rate, first speeding it up and then slowing it down. Both of these changes handicap a man working under high air pressure. Alcohol also promotes the absorption of nitrogen into the system. Although no serious accidents have ever happened at the school, under actual working conditions the diver is constantly stalked by death. Two of the most serious accidents that can befall a man are a “blowing up” and a “squeeze.” In the former, a diver blows quickly to the surface due to excess buoyancy. Because of the rapid decrease in water pressure, his dress may burst. If he loses a shoe, he may dive headfirst and drown. If he escapes these difficulties, he must inevitably get the dreaded bends, unless he is sent down again immediately, or put into a recompression chamber. In a “squeeze,” a diver falls a considerable distance while under water. The outside water pressure becoming suddenly greater than the air pressure within the dress, the diver’s body is jammed up into his helmet. He is generally killed instantly. In a number of cases it has been impossible to remove a diver from his helmet after a squeeze. And what is the reward for this work and risk? Graduates of the Deep-Sea Diving School are designated as Divers, First Class. As such they rate fifteen dollars a month extra pay, plus a bonus at an hourly rate while employed in actual salvage operations in depths over ninety feet!

Popular Mechanics, v. 75, n. 3, 1941

Popular Mechanics, v. 75, n. 3, 1941