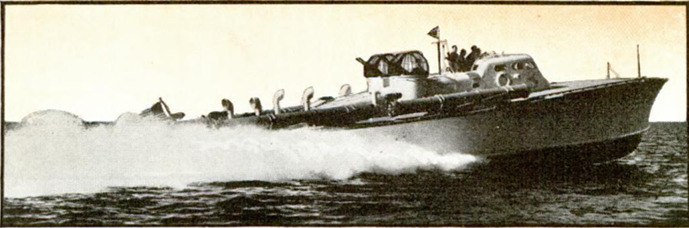

EVEN in a calm sea the toughest tars in Uncle Sam’s Navy feel their knees buckling as the mosquito fleet bangs across the bay at fifty knots. And when you ride one of these floating bronchos at top speed down the slope of a fifteen-foot wave and smack head-on into that green wall of water on the other side - well, this is no place for a weak pair of legs or an uncertain stomach. Hand and toe grips are no great aid and comfort, and the old boatswain’s command of “Both feet on the deck, sailor!” brings a grim laugh. The men who designed these boats planned them to fulfill a mission - getting somewhere in a grand hurry, doing a job, and pulling away with the same initial speed. It's up to the crewmen to work outtheir personal problems. Grabbing a bite to eat is one of them, and a serious one. You may be able to munch a sandwich while clinging to the saddle of a wild horse, but try downing a cup of coffee; and coffee is the standby of all good sallors. Manning battle stations, firing machine guns, launching torpedoes must all be accomplished under the same violent conditions - plus, in actual combat, the hazards of facing dive bomber and battleship fire. No wonder the sailors of the mosquito fleet have to be tough. They may be called upon to “take it” for twenty-four hours at a stretch. Some Navy veterans who volunteered for the service had to quit and go back to the broad decks of the battleship, quiet as country lanes in comparison with the fast little torpedo boats. Changing of watch and shifting stations must always be done beneath battened-down hatches. To use the deck would be suicidal. Going off duty, the men climb into their bunks and immediately strap themselves in to relax and dream of tobogganing through a boulder field. Seamen in every sense of the word, these men are also specialists in gunnery, torpedo work or mechanics. Their training in these boats has been carried out hand in hand with construction development; they are familiar with the capabilities as well as the limitations of the craft. Their job thusfar has been to test the mosquito boats to the limit and report any weakness. Already the first boats of the fleet are back from the prescribed test runs for certain modifications to improve their performance, changes that are being incorporated in the boats now building. Ask any member of the crew what he thinks of the new boats and he'll tell you: “They’re pretty good, but we're not finished with them yet. Wait until we've had a chance to test out the latest modifications, and if those boats can take it, so can we.” The latest mosquito boats are considered self-sustaining for five days - that is, living quarters and other arrangements are supposed to be adequate for that time. Why was the five-day period decided upon? That’s a Navy secret, but it is possible to visualize certain uses to which the boats could be put and to make a logical surmise of areas where they will operate which would require five days’ absence from regular bases; patrol in the Caribbean and off our own coasts, the entrances to the Panama Canal and the areas around our island possessions. These operations would call for definite assignment to the fleet, for they would be part and parcel of the possible major engagements. At this stage of the game their assignment is pure conjecture, but not for long. Right now every opportunity is being given to these boats to demonstrate their greatest usefulness to our Navy. That is the main reason why both the boats and the sailors who man them are being subjected to such grueling tests of endurance. Only in this way can be determined the highest capabilities of both under the most trying and hazardous conditions. This work is listed in Navy records under the prosaic heading “Third stage of development - Operations.” ‘The war in Europe brought to the attention of the world many new instruments of warfare and new employment of old ones. Certainly the motor torpedo boats used by Germany, Italy, Great Britain, and France fired the popular imagination. In addition, the official mind was vitally interested. No one had forgotten the spectacular use of small high-speed boats in the first World War, against the largest units of opposingfleets. And the United States had not been calmly viewing the developments of other countries and doing nothing itself. When word came from the commander-in-chief in 1939 to investigate the possibilities of the small-boat field, the Navy was ready to “yp-anchor” on the project immediately. The Bureau of Ships at once purchased the latest design of British motor torpedo boat. Demonstrations were conducted and performances compared with the known capabilities of similar boats used by France, Italy and Germany. These data were compared with those of our own efforts of the past twenty years with aviation rescue boats. Within a few months developments had reached the point where the Secretary of the Navy could award a contract for twenty-three boats. Eleven were fitted as motor torpedo boats and twelve as motor submarine chasers. All were powered with the latest type of Packard engine. First, our own geographical situation, continental and outlying possessions, had been considered; second, the greatest value to be derived from their employment was studied. On these considerations the building specifications were based. The Italian government had found that boats varying in length from forty to seventy feet, pow- ered with Isotta-Fraschini engines, capable of over forty knots were most suited for warfare in the Mediterranean. The French favored boats not over sixty feet, with one or two torpedo tubes and possessed of forty-five knot speed. The British boatsvaried in length from sixty to seventy feet and were powered with Rolls-Royce engines. The Germans had adopted a boat approximately ninety feet long with two twenty-inch bow torpedo tubes and were convinced that the Diesel engine, and thirty-knot speed, fitted their particular needs. Information concerning operations abroad, combined with experience in the operation of our own twenty-three boats, gave a pretty good survey of the small boat field, The Navy arranged a design competition, and the final design allowed for fifty-nine and eighty-one-foot lengths of V-bottom, hard-chine, stepless boats. Contracts were let for quantity production. Primary consideration was given to weight saving wherever practicable. Aluminum was widely used for superstructures, gasoline tanks, drainage piping, doors, hatches, manholes and scuttles, ladders and engine foundations. Also, a great amount of plywood was employed. These measures have resulted in approximately a ten per cent lighter boat than the original models of the design competition, In preliminary tests the smaller mosquito boat hit sixty-two knots, or seventy-two miles an hour. The eighty-one-foot craft should hit eighty-five miles an hour. On a trial run in New York harbor the PT-10, American-built, with three Packard supercharged marine engines of 1,500 horsepower each, amazed skippers of passing tugboats by roaring along at fifty knots without disturbing the waters, for even at high speed they leave little wake. The Scott-Paine type of mosquito boat, following a British design, mounts four eighteen-inch torpedo tubes and four machine guns in turrets, and carries an officer and eight men. The boats have small electric refrigerators and hot plates; cooking at sea is limited generally by cramped quarters, slapping of the sea, and appetites if the men to soup, coffee, sandwiches and fruit, At twelve knots the mosquitoes can cruise over a 3,000-mile range. They will probably take on a variety of missions in war: coastal patrol, convoying, attacks against enemy vessels - at night they can muffle engines for a silent approach; by day, a dozen mosquitoes could dash against an enemy squadron at a mile a minute, fling out forty-eight torpedoes in five sec- onds, wheel around and be gone. They also carry smoke-screen apparatus. The boats are standing up in great style. Training of men especially picked from volunteers goes on without interruption, both ashore and afloat. They know intimately the construction of their boats as well as every phase of operation. They are sure of the amount of punishment their craft can take if put to it. The least of the Navy's worries is the performance of its personnel, for nowhere in the world is there a group so distinguished by their intelligence, loyalty and ability - both officers and enlisted men. In their hands may safely be placed the problem of finding the most effective use for the boats, whether as single units or in swarms, emulating the mosquito for which they are named.

Popular Mechanics, vol. 75, n. 4, 1941

Popular Mechanics, vol. 75, n. 4, 1941