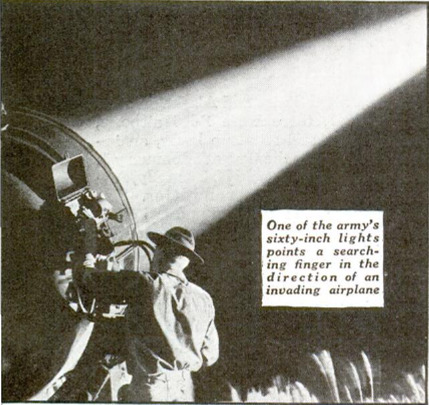

THE forward march of science has been so rapid most of us have missed the significance of one far-reaching change - the overshadowing of the picturesque, lone inventor by the huge research laboratory. Everyone knows what men like Edison and Marconi did for civilization, but no one can name the sole inventor of dozens of new things like rayon, synthetic rubber, plastics, pliable transparent fabrics, television or the modern, practical automobile and airplane. They are many-sided research laboratory inventions in which many men and many minds contributed anonymous parts. This teamwork system may have eliminated some independent experimentation, but if giant enemy bombers ever dot our night skies we will have reason to appreciate the coordination made possible by these laboratories. One advantage of organized research is that these trained engineers can be formed into specialized divisions, like sections of an army, and each group assigned to a specific problem. That is exactly what is happening. Laboratories are being enlisted for war duty by a government agency. Thousands of research engineers have already turned from their efforts to make life easier to a grim, new task, to make our life safer. They are applying themselves to improving the accessories of death - explosives, weapons, gun turrets, torpedoes, anti-aircraft detectors, searchlights, bomb sights, gunfire controls, protective armor, communications_systems, warfare chemicals, blackout devices, gas masks and so on. Naturally most of the results these experts have obtained are secret, so secret indeed that if war is to be the fate of this nation, Americans themselves will be surprised at some of the things they have developed. But the preparations for civilian protection already worked out by one of the dozens of great research organizations are no secret. The organization is the illuminating laboratory of the Geaeral Electriccompany at Schenectady, N. Y. And the activities of these scientists-goa long way toward throwing light on U. S. defense, forlight is their specialty. For instance, it will not be necessary to “black out” American homes and industrial plants, as they have in Europe, by turning out lights, or covering windows and doors with stuffy fabrics or solid shields. H. A. Breeding, physicist at the Schenectady illuminating laboratory has shown that a combination of blue-painted windows and yellow sodium lighting in factories and homes is one answer to this problem. Breeding uses ordinary paint treated with a special blue dye; windows so treated will admit daylight. But, more important in war time, buildings can be lighted inside with sodium lights, not one flash of which will escape through the blue windows at night to guide raiding planes. A sheet of this blued glass blots out sodium light completely because, unlike daylight and incandescent light, it contains no blue to be transmitted. The ultra-violet rays of the mercury lamp, popularly known as “black light,” can also be used if enemy air raids reach this continent. “Black light” rays are invisible to the eye, but can be detected by fluorescent paints which could be used on sign posts at street intersections to direct pedestrians, and along curbing to guide motorists. In the event of all-nightblackouts, the lighting of store windows can be so arranged as to be invisible from the sky by using low-intensity lights and special reflectors which would direct light away from the street and toward the back of the window where it would be absorbed in a dark backdrop. Luminescent paints and black light will also find application here. General Electric engineers are experimenting with another device which would enable electric power stations to turn out street lights in five seconds without disrupting other electrical service to homes and industry, if air raids threaten. The lights can be returned to normal operation five seconds after the “all clear” signal. At present, such quick control of street lights is not possible without disruption of all electric service or the use of expensive equipment now in operation in only a half dozen cities. Most street lights are turned on and off by time switches, or by power men who must travel to numerous control points in a city. Obviously these methods are outmoded in time of war, unless all street lights are made to operate at a very low intensity, invisible to aerial raiders. The scientists are also working on this angle. According to these experts, present street lights can be virtually blacked out by the use of low-intensity shaded bulbs barely visible to persons on the ground, and completely invisible to air raiders. For defense against enemy planes, General Electric is building giant sixty-inch searchlights. The powerful lights spot airplanes five miles high, and help keep them at a great height where accurate bombing is difficult. These same lights can be used in coast defense work against warships, spotlighting them far out at sea and enabling shore guns to be brought into action. A newspaper can be read by their light in an airplane twelve miles away. Many factories are already on twenty-four-hour-a-day production schedules to speed construction of war equipment. Saboteurs will try to destroy plants and the products they are making. These agents prefer to work at night, but the illumination engineers have worked out protective apparatus - brilliant lights to protect the fences which surround most industrial plants, and high-powered searchlights atop guard houses to spot the saboteur. In restricted areas, the photoelectric eye is being employed to detect persons who try to gain access without permission. Auxiliary lighting systems, which might be used if the main power supply fails, have been developed. These operate from gasoline generators or storage batteries and are also being built into trucks, forming portable emergency lighting equipment that will step in when central power stations are bombed. Floating power stations are also planned. Just as the General Electric illuminating laboratory did not wait to be recruited for war time service, the functions of the research laboratory will be shifted until it is operating almost entirely on the problems of U. S. defense, according to Laurence A. Hawkins, executive engineer. He says: “Research is essentially building for the future. It is a systematic search for new knowledge on which new industries may be erected or old industries radically improved. It leads to increase in the national wealth and a raising of the standard of living. But there come times when even such worthwhile aims must be temporarily abandoned. If a conflagration threatens one’s house, it is foolish to sit planning additions while the flames creep nearer. “This is precisely the situation as regards research in this country today. Once again our nation has been aroused from complacent unpreparedness to mobilize its great resources. Once again American research must and will play its part. “War is mechanized as never before. Given time, American research, American engineering and American genius for mass production, which have made this nation the strongest industrially in the world, can “nake us also the strongest in arms. “Not a day must be wasted. We must not gamble with the national safety. We, in our laboratory, are more than eager to help. to the utmost limit of our ability.” Which is one way of warning the embittered world: “If war comes, we'll be ready over here.”

Popular Mechanics, vol. 75, n. 4, 1941

Popular Mechanics, vol. 75, n. 4, 1941