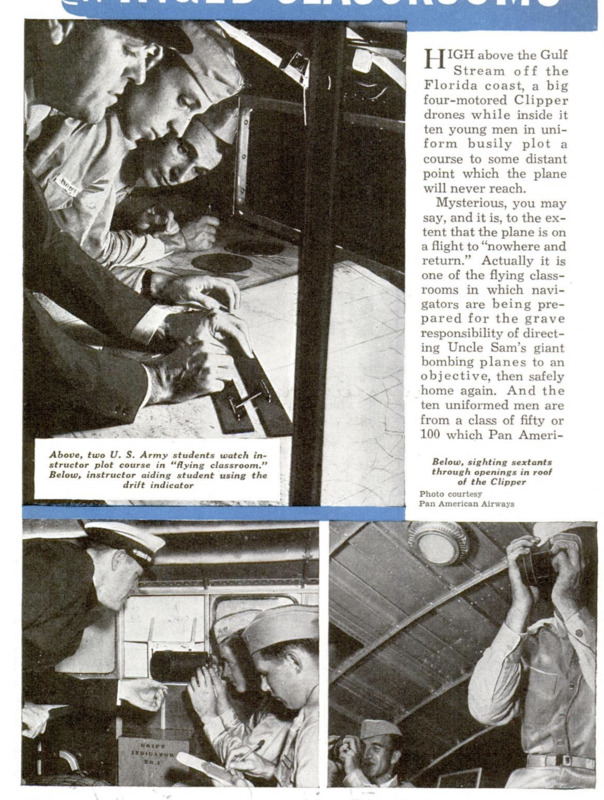

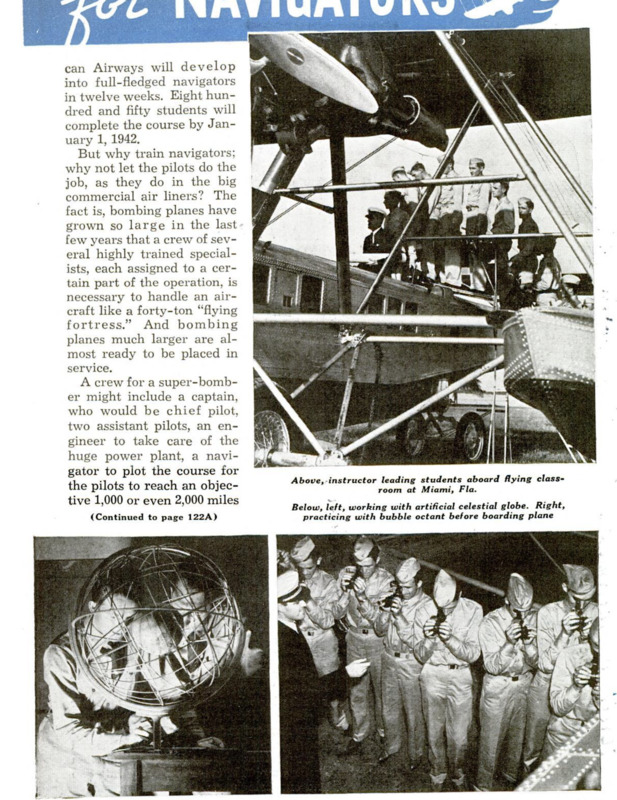

HIGH above the Gulf Stream off the Florida coast, a big four-motored Clipper drones while inside it ten young men in uniform busily plot a course to some distant point which the plane will never reach. Mysterious, you may say, and it is, to the extent that the plane is on a flight to “nowhere and return.” Actually it is one of the flying classrooms in which navigators are being prepared for the grave responsibility of directing Uncle Sam’s giant bombing planes to an objective, then safely home again. And the ten uniformed men are from a class of fifty or 100 which Pan American Airways will develop into full-fledged navigators in twelve weeks. Eight hun- dred and fifty students will complete the course by January 1, 1942. But why train navigators; why not let the pilots do the job, as they do in the big commercial air liners? The fact is, bombing planes have grown so large in the last few years that a crew of several highly trained specialists, each assigned to a certain part of the operation, is necessary to handle an air- craft like a forty-ton “flying fortress” And bombing planes much larger are almost ready to be placed in service. A crew for a super-bomber might include a captain,who would be chief pilot, two assistant pilots, an engineer to take care of the huge power plant, a navigator to plot the course for the pilots to reach an objective 1,000 or even 2,000 miles away, a radio operator, a bombardier to operate bomb sights and releases and two or three gunners. Since the success of a long-range bombing flight depends first of all upon reaching the objective, the navigator’s role is highly important. Because Pan American Airways had developed the multiple-crew system to a high degree of efficiency in commercial service that spanned the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans, the War Department called upon that organization to train navigators for the Air Corps’ bombers. The airways company provides the instruction, which is given by some of its most experienced personnel, and all flight-training facilities, including three big Clippers, on a non-profit contract basis. The Clippers are the only big ships capable of taking ten to twelve men aloft at one time with the large desks and many instruments required for each student. Too, by operating from the navigation training base at Miami, Fla., the Clippers afford an opportunity for the students to gain experience on long flights over the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. Pan American’s direction-finding stations cover the Florida waters and offer the embryonic navigators additional facilities for their work in the flying classrooms. As the big Clipper soars above the Florida shore, one of Pan American’s experts walks from one to another of the ten navigating compartments into which the ship’s interior is divided. Here he finds a student entangled in the complexity of a drift problem, there he discovers an error in course that would result in the Clipper missing its mythical destination by hundreds of miles. Quickly he solves the problems, then goes on to others. Under his watchful eye, the students learn the three methods of position finding - dead reckoning, radio direction and celestial navigation. The last mentioned is important in wartime flying when radio beams cannot be used lest they become an aid to enemy pilots. The students must become proficient in determining position by observation of the sun, moon, stars and planets, Each must know the relative positions of more than fifty prominent stars. Ground practice with instruments comes first, so the cadets may be able to work swiftly aboard their school ship. Only ten to fifteen minutes can be allowed for calculations made from sights of celestial bodies, for instance, due to the speed of travel. Meteorology is another subject of serious study in the navigation training. It includes information on fronts and their effects, reading and analyzing of weather maps and coordination of government and private weather information and data. In the short course of twelve weeks, it is impossible to go into the detail necessary for students to learn formulation of weather maps, so merely the interpretation of them is undertaken. How to determine and conquer that enemy of aviation, drift, is another important phase of work for the cadets, but they have an invaluable aid in an instrument which measures the angular difference between the directional line of the airplane and the apparent line of motion of a single wave sighted on the ocean far below, thus enabling the navigator to estimate accurately the drift of a bombing plane and so maintain a predetermined course. The cadets spend each day, six days a week in this manner: four hours of navigation, divided into two sessions of two hours each; one hour of meteorology; one hour for lunch; two hours of military training and two hours of homework. When ground lessons have been completed, four hours in actual flight are substituted for the navigation period. Each flight occupies four hours and one-third of the flights must be made at night, to accustom the cadets to conditions under which they may find themselves plotting a course through inky darkness for the pilot of a bombing plane bound for an objective hundreds of miles away. Flight courses are never announced in advance, so the students literally are bound for “nowhere and return” when they board the flying classroom. Although the navigation students do not learn to pilot a plane, they are chosen in much the same manner as those accepted as flying cadets. They are enlisted in the U. S. Army Air Corps; they are between twenty and twenty-seven years of age, unmarried and they agree to serve for three years, then hold themselves ready to serve an additional three years if needed.