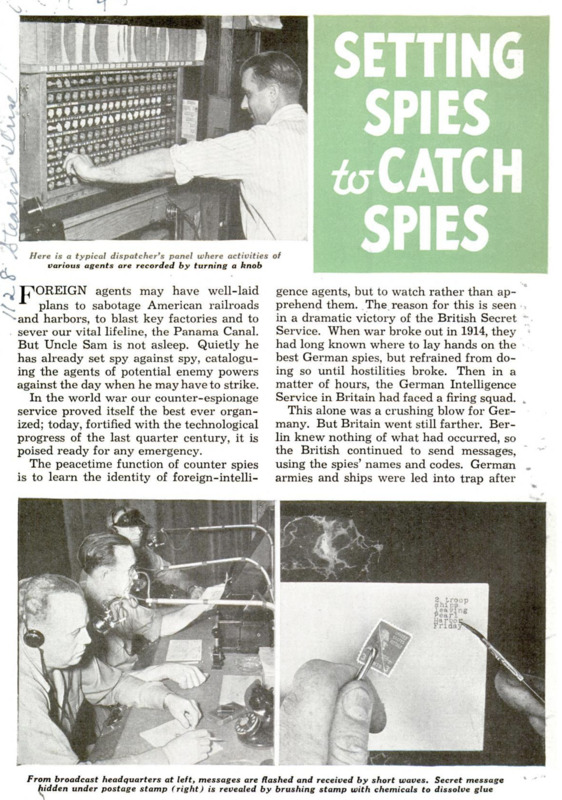

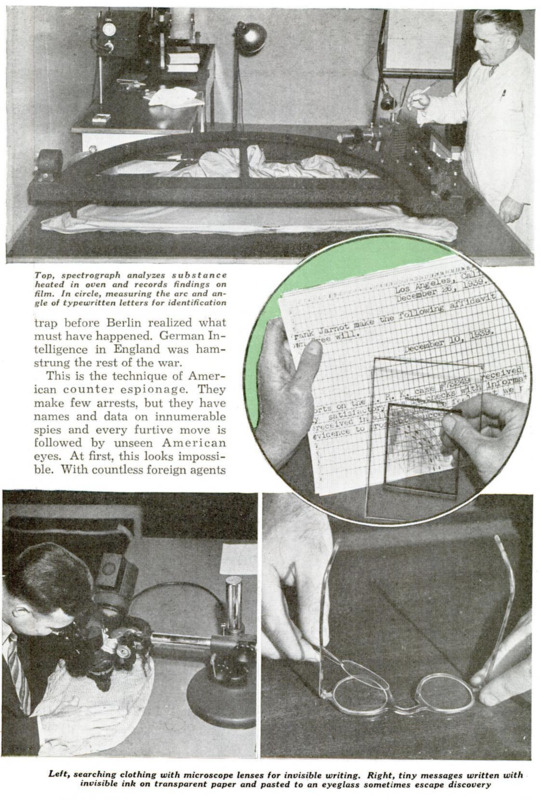

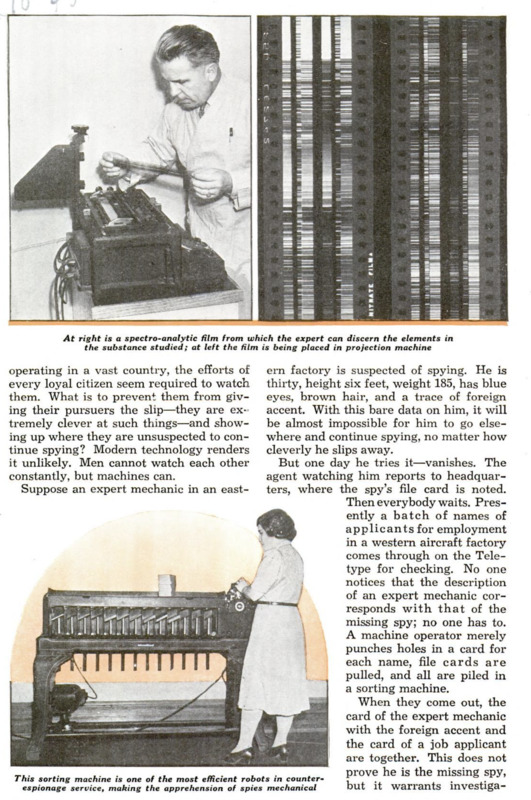

FOREIGN agents may have well-laid plans to sabotage American railroads and harbors, to blast key factories and to sever our vital lifeline, the Panama Canal. But Uncle Sam is not asleep. Quietly he | has already set spy against spy, cataloguing the agents of potential enemy powers against the day when he may have to strike. In the world war our counter-espionage service proved itself the best ever organized; today, fortified with the technological progress of the last quarter century, it is poised ready for any emergency. The peacetime function of counter spies is to learn the identity, of foreign intelligence agents, but to watch rather than apprehend them. The reason for this is seen in a dramatic victory of the British Secret Service. When war broke out in 1914, they had long known where to lay hands on the best German spies, but refrained from doing so until hostilities broke. Then in a matter of hours, the German Intelligence Service in Britain had faced a firing squad. This alone was a crushing blow for Germany. But Britain went still farther. Berlin knew nothing of what had occurred, so the British continued to send messages, using the spies’ names and codes. German armies and ships were led into trap aftertrap before Berlin realized what must have happened. German Intelligence in England was hamstrung the rest of the war. This is the technique of American counter espionage. They make few arrests, but they have names and data on innumerable spies and every furtive move is followed by unseen American eyes. At first, this looks impossible. With countless foreign agentsoperating in a vast country, the efforts of every loyal citizen seem required to watch them. What is to prevent them from giving their pursuers the slip - they are extremely clever at such things - and showing up where they are unsuspected to continue spying? Modern technology renders it unlikely, Men cannot watch each other constantly, but machines can. Suppose an expert mechanic in an eastern factory is suspected of spying. He is thirty, height six feet, weight 185, has blue eyes, brown hair, and a trace of foreign accent. With this bare data on him, it will be almost impossible for him to go elsewhere and continue spying, no matter how cleverly he slips away. But one day he tries it - vanishes. The agent watching him reports to headquarters, where the spy’s file card is noted. Then everybody waits. Presently a batch of names of applicants for employment in a western aircraft factory comes through on the Teletype for checking. No one notices that the description of an expert mechanic corresponds with that of the missing spy; no one has to. A machine operator merely punches holes in a card for each name, file cards are pulled, and all are piled in a sorting machine. When they come out, the card of the expert mechanic with the foreign accent and the card of a job applicant are together. This does not prove he is the missing spy, but it warrants investiga-tion. Teletype flashes instructions to give him a job, and obtain his fingerprints without arousing suspicion. Headquarters probably has his prints already. If not, the program of fingerprinting all aliens will soon remedy that. Later, the suspect, working at his bench, lays down a wrench. His neighbor unostentatiously stirs up dust, which settles on the handle, bringing fingerprints into sharp relief. Then he stands above the wrench and a hidden camera photographs that wrench, Counter espionage will soon know if the missing spy has been found. Once this would have been impossible. Men could not possibly sort by hand the bulky files necessary to keep track of thousands of individuals by description. Sorting machines do the job in a few seconds. But why does Intelligence suspect a man is a spy? If he is clever, won't he avoid throwing suspicion on himself? Perhaps, but someone else is likely to throw suspicion on him. All spies are part of organizations. There will always be one spy who will brag too loudly, or spend more than his salary, or get clumsy trying to steal secrets. He will be watched constantly. His mail will be scanned. This may lead to spy headquarters. If so, Intelligence will watch mail entering and leaving the place. Often letters coming to such a place will have no signature. Counter spies learn who wrote it by teletyping headquarters, “Who could know - " and repeating the message. Again the sorting machines go to work. A list of suspects is compiled. Counter spies investigate each individual. A sample of his handwriting or from his typewriter is measured against intercepted messages for comparison. A bit of his stationery will be taken for spectro-analysis to see if the intercepted message is on the same paper. Spies have devised many clever means to shoot messages past counter agents. Writing a message on transparent paper with invisible ink, and pasting it to an eye-glass is one that still works. Writing minutely under a postage stamp is another. Maps have been drawn on women'’s fingernails and covered with polish. An Oriental importer was a known spy, but they couldn’t find where he concealed messages until someone realized that Chinese characters decorating pottery, statuary, etc., were in reality writing in Chinese. Even the once reliable writing in invisible ink is of little value now. One of the routine tasks of a censor is to hold every opened letter beneath an ultra violet lamp, where invisible writing shows up vividly in colors. There are, however, hard messages to intercept, and chief of these is the stencil type. A spy writes a chatty, gossipy letter about nothing much, which contains a hidden message which will be revealed when a stencil, with slits at intervals to reveal only the key words, is placed over the entire message. Here is an example: “On June 1, Virginia is getting married, and mother is all broken up over the division of the family. They are leaving to live permanently in New York on the 5th, after their honeymoon.” Would a good censor pass that? Never! Censors are trained to look for words with double meanings, and two here would stop a good censor short: “Virginia” and “division.” One is a girl's name, but also the name of a place; the other means a split, but also a contingent of soldiers. In a few moments, a skilled censor would detect the message: “Virginia division leaving New York on the 5th.” Not all stenciled letters are that easy, and some do get by. It is probably the best means of war-time communication between agents, save when a spy can slip through and deliver his message in person. Isolation from our possible enemies by oceans makes that practically impossible for spies operating here. We are truly as hard to spy on as to invade, because of a fine organization and fortunate isolation. That is why most spy scares turn out to be sheer moonshine, and would be funny if they didn't send frightened people on a witch hunt that sometimes results in injury to an innocent party. Recently there was a “hot” story about a plan to blow up Boulder dam. Vigilantes stood by with rifles, fortunately shot no hapless tourist, and nearby residents prepared to flee. Finally someone calmly inquired where was the carload of explosives necessary to do such a job, and panic retreated before common sense. There is a spy menace, and it is a serious business. But Uncle Sam has it in hand.