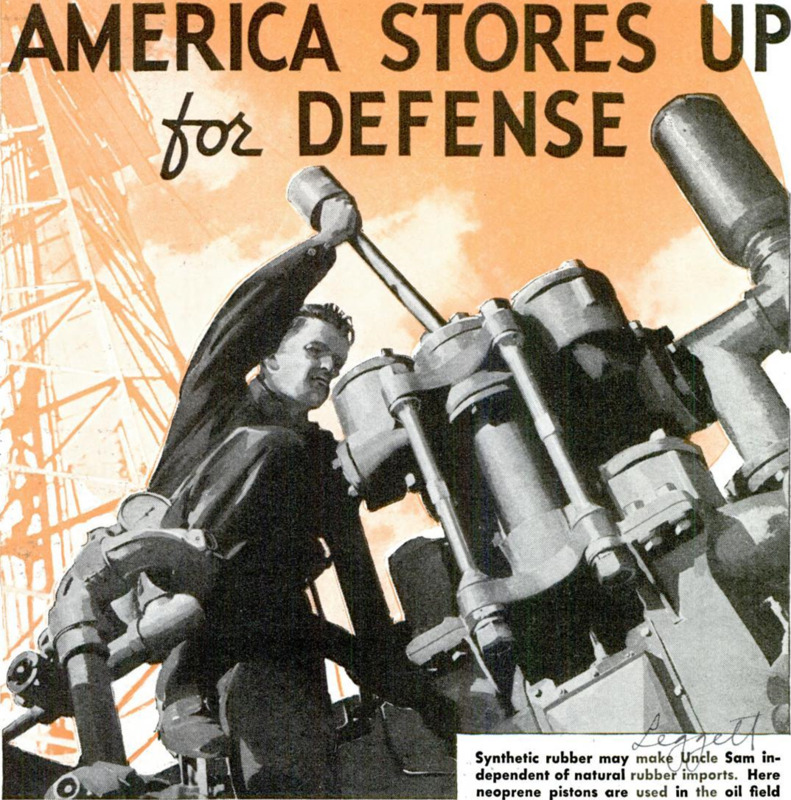

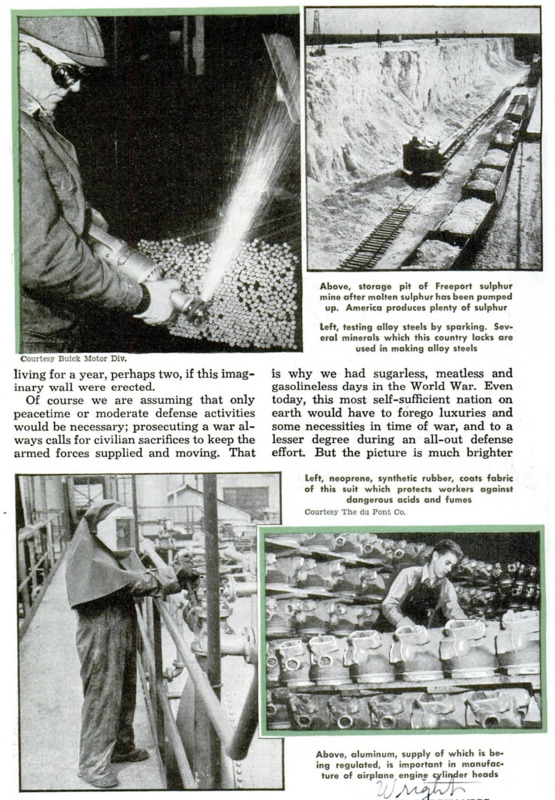

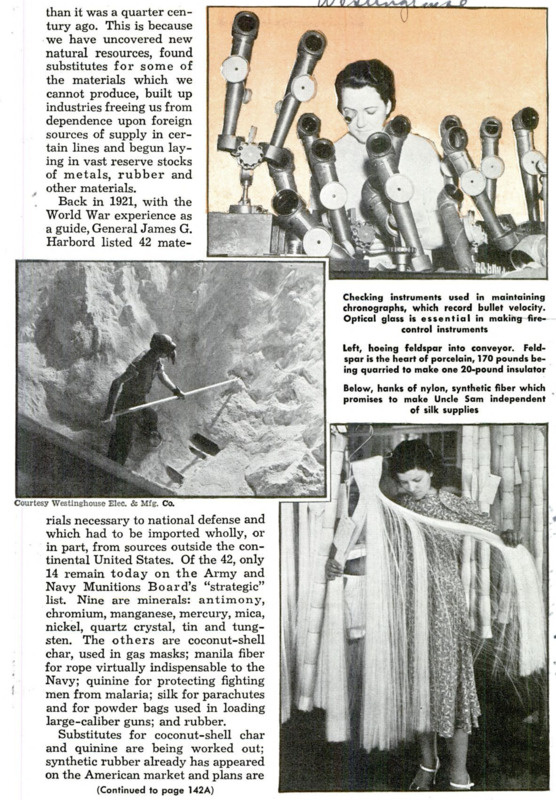

IF THE United States were cut off suddenly from the rest of the world - an extreme case of complete isolation that is highly improbable though we are already cut off from some areas - we could view the situation with far less alarm than was felt in 1914 when blockades began pinching off the supply of materials flowing to this country. While it would be gross exaggeration to say that this nation could get along indefinitely on its present scale of essentials without imports, it is safe to predict that few would be missing from our scheme of living for a year, perhaps two, if this imaginary wall were erected. Of course we are assuming that only peacetime or moderate defense activities would be necessary; prosecuting a war always calls for civilian sacrifices to keep the armed forces supplied and moving. That is why we had sugarless, meatless and gasolineless days in the World War. Even today, this most self-sufficient nation on earth would have to forego luxuries and some necessities in time of war, and to a lesser degree during an all-out defense effort. But the picture is much brighter than it was a quarter century ago. This is because we have uncovered new natural resources, found substitutes for some of the materials which we cannot produce, built up industries freeing us from dependence upon foreign sources of supply in certain lines and begun laying in vast reserve stocks of metals, rubber and other materials. Back in 1921, with the World War experience as a guide, General James G. Harbord listed 42 materials necessary to national defense and which had to be imported wholly, or in part, from sources outside the continental United States. Of the 42, only 14 remain today on the Army and Navy Munitions Board’s “strategic” list.” Nine are minerals: antimony, chromium, manganese, mercury, mica,nickel, quartz crystal, tin and tungsten. The others are coconut-shell char, used in gas masks; manila fiber for rope virtually indispensable to the Navy; quinine for protecting fighting men from malaria; silk for parachutes and for powder bags used in loading large-caliber guns; and rubber. Substitutes for coconut-shell char and quinine are being worked out; synthetic rubber already has appeared on the American market and plans are under way to produce enough to meet one-sixth of our annual needs; and a substitute for silk – nylon - is being manufactured but not in quantities sufficiently large to supplant the imported material immediately. In an emergency it might be possible to step up our production of tungsten to a level close to requirements - at least for a limited time. Fifty per cent of the tungsten necessary for peacetime has been produced from domestic mines during the last five years. In the high speed tool steel field where tungsten has been used as an alloy, molybdenum has been found a satisfactory substitute. Domestic output of mercury, which normally supplies about 40 per cent of our consumption, has been increased sufficiently to take care of all our needs and allow some export to England. With the possible exception of tin, the outlook for supplies of the nine strategic minerals for at least a year, and in most instances two years, is good, due to the foresight of industry in building up large stock piles and to the government’s policy of laying in vast reserves. A subsidiary of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, the Metals Reserve Company, is financing imports of reserve stocks of tin, 75,000 tons within one year, manganese ore, 1,000,000 tons within three years, chromium, tungsten and antimony. Purchases for 1941 and 1942 probably will be double those for 1940, which were higher than usual for most of the five minerals. Total imports of tin increased notably during 1940, exceeding 1939 receipts by a large margin. Arrivals of crude rubber reached a record level during the third quarter of 1940 and the year's receipts were about 50 percent above those for 1939, By the end of this year, provided there is no interruption of shipping, government-held stocks are expected to total 416,000 tons, over and above current requirements. At the same time private stocks are expected to increase to a point where this country will have more than a year’s supply, roughly 600,000 tons. This does not include an anticipated production of 200,000 tons of reclaimed rubber and an increasing quantity of synthetic rubber. Of the 28 items removed from the Harbord strategic list, chemistry has made it possible for us to produce about 25 percent of them from domestic raw materials and developments in metallurgy and other sciences are responsible for our self-sufficiency in others. Among those which, thanks to the chemist and metallurgist, are no longer regarded as strategic are: camphor, nitrates, iodine, optical glass phosphorus, potash and vanadium. Others taken from the list through development of replacement materials, discovery of adequate domestic sources of supply, or for other reasons such as building up large reserves of imports include: arsenic, asphalt, balsa wood, coffee, cork, graphite, hemp, hides, jute, kapok, linseed oil, opium, palm oil, platinum, sugar, sulphur, shellac and uranium. Coconut-shell char and quinine may be removed soon from the list of today. Optical glass, so essential to defense because it is used in field glasses, cameras, fire-control and range-finding instruments, microscopes and lenses with which any modern army and navy must be equipped, now is listed as a “critical” material - equally essential as strategic materials and which may offer some difficulty in obtaining an adequate supply, but does not present as great a problem as the strategic materials. The World War found the United States entirely dependent upon foreign sources for this glass so a study was inaugurated at the Bausch and Lomb plant in 1917, This effort resulted in producing a few essential types of optical glass and in expanding facilities. By August, 1918, five plants were turning out enough to meet all military and naval needs. Since then many new types have been developed and now the United States is considered independent of outside sources for its peacetime supplies. However, reserve stocks have been acquired from abroad to meet all requirements of an emergency until domestic production could be stepped up to satisfy all demands. Similarly this nation has been freed of dependence upon outside supplies of sulphur, so widely used by the petroleum, iron and steel, fertilizer, pulp and paper, rubber, dyes, coal-tar products and chemical industries. This has been achieved by development of vast domestic resources such as the Freeport Sulphur Company’s Grande Ecaille mine in the Louisiana marshlands near the Gulf of Mexico. Here sulphur is mined by forcing superheated water down pipes to the sulphur-bearing | formations. The sulphur melts and is pumped to the surface. Better than 99% per cent pure, it is then pumped to huge storage vats where it cools and solidifies, later to be broken up and shipped. In 1912 Freeport produced 636 tons; today the company’s annual output exceeds 750,000 tons a year. Manganese, one of the nine minerals of which we have insufficient supply for peacetime needs, is the starch that goes into the laundering of steel. This country uses about 1,000,000 tons per year, about 14 pounds going into every ton of steel. Without it, modern steel rails soon would crumble or spread under the impact and weight of big locomotives. Since manganese is vitally necessary for special purpose steels, such as those found in large army and navy guns, it is highly essential to national defense. A different grade is employed in making dry batteries. Our present stocks would be sufficient for nearly two years at the current rate of consumption. Cuba has been supplying part of the manganese ore purchased recently by this country. Although the island’s ores are low-grade, special concentration treatments result in a product suitable for making steel. This activity is carried on by the Cuban-American Manganese Corporation which was awarded a contract to supply the U. S. government with the first 25,000 tons of the mineral purchased under legislation authorizing the piling up of strategic material reserves for national defense. In an emergency the Cuban process might be applied to low-grade manganese deposits in this country. Chromium, too, is highly essential in the manufacture of alloy steels, as well as in the tanning of leather, the making of pigments and in electroplating. Our imports are chiefly from southern Africa, the Phil- ippines, New Caledonia, Cuba and Turkey. Domestic resources of metallurgical grade ore are virtually nonexistent and reserves of lower grade material are extremely limited. In Canada processes are being developed and tried to make ferrochrome, which contains 65 to 72 per cent chromium, from lower grade ores but these are not yet commercially successful. If they should be they will contribute to making the United States self-sustaining. Tin presents one of our serious strategic mineral problems because it is indispensable for so many uses and there is very little production in this country. The metal serves as the protective coating on steel from which our tin cans are made and is employed in making bearings, solders, bronzes and gun metal. Under normal conditions, this nation’s consumption is 75,000 long tons per year, or about 45 per cent of the world output. In order to reduce our consumption and thus become more self-sufficient, synthetic resin enamels have been tried as coatings for certain types of cans and chemically treated cardboard containers have been produced for various products. In addition, work has been done looking toward the use of silver and aluminum as substitutes for the coating of tin cans. Tinless alloys for machine bearings also have been used to some extent. The world’s principal producers of tin ore are the Malay States, Dutch East Indies, Bolivia, Siam and China. Bolivian ore has had to be sent to Europe for refining because there are no important smelting facilities in the western hemisphere. However, in connection with an agreement with Bolivian tin producers and their government, plans are being made to provide smelting facilities in the United States. For military purposes, antimony combined with lead is used to make bullets, both for small arms and as shrapnel. It is also employed in the manufacture of storage battery plates. Mexico is one of our principal sources of the metal and a smelter established at Laredo, Tex., treats Mexican ores and sells the product in the United States. During the past 10 years, roughly 10 per cent of our requirements have been met by domestic production. Quartz crystal, particularly of the grade employed to control the frequency of radio transmitters, comes to us from Brazil, since we have none of a quality suitable for that purpose. Even the Brazilian product is far from ideal, only about seven tons out of 250, the approximate annual output, being suitable for radio equipment. Cutting crystals for this purpose requires great accuracy with reference to thickness and also in the direction of the various axes of the crystal. The average size of the finished radio crystal is about one by one by one-tenth inch. Tourmaline, a mineral found in California, might be a possible substitute in an emergency, since it possesses desirable properties of this type. Nickel, a silvery-white metal, finds usage in armor plate, armor-piercing projectiles, gun barrels, recoil cylinders. An alloying ingredient in steel to give increased hardness, toughness and strength, nickel is produced in only small quantities in the United States, most of our supply coming from Canada. Our annual requirements in the near future may be assumed at 45,000 to 50,000 tons under normal conditions. On all these, and sheet mica, too, which is used as armature winding tape, commutator segments, rings, cones and transformers, Uncle Sam is stocking up, looking to the day not far away when this nation will have a two-year supply of things necessary to defense which cannot be produced at home. Given that much leeway in an emergency, there is a good chance that the Bureau of Mines, the Geological Survey and other governmental agencies, working together with private research experts and industrial management, will be able to develop our own sources of supplies or substitutes that will make us self-sufficient as long as may be necessary.

Popular Mechanics, v. 75, n. 5, 1941

Popular Mechanics, v. 75, n. 5, 1941