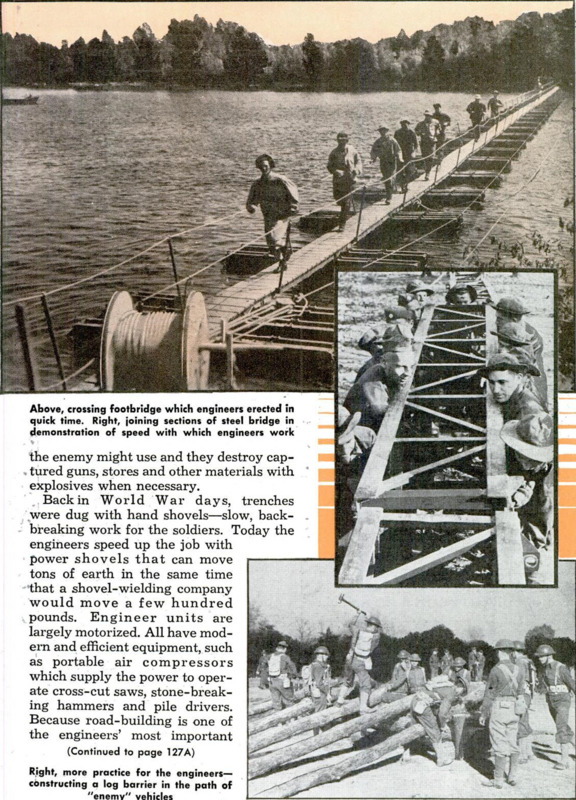

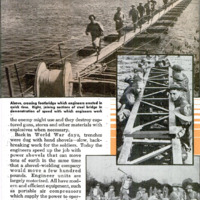

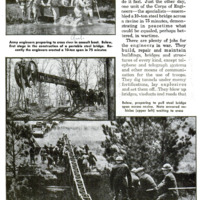

IF Uncle Sam’s Army needs a bridge built, mines laid, trenches dug, roads constructed or a power system set up, its own specialists do the job - and do it fast. Just the other day, one unit of the Corps of Engineers - the specialists - assembled a10-ton steel bridge across a ravine in 75 minutes, demonstrating in peacetime what could be equaled, perhaps bettered, in wartime. There are plenty of jobs for the engineers in war. They build, repair and maintain buildings, bridges and structures of every kind, except telephone and telegraph systems and other means of communication for the use of troops. They dig tunnels under enemy fortifications, lay explosives and set them off. They blow up bridges, viaducts and roads that the enemy might use and they destroy captured guns, stores and other materials with explosives when necessary. Back in World War days, trenches were dug with hand shovels - slow, back-breaking work for the soldiers. Today the engineers speed up the job with power shovels that can move tons of earth in the same time that a shovel-wielding company would move a few hundred pounds. Engineer units are largely motorized. All have modern and efficient equipment, such as portable air compressorswhich supply the power to operate cross-cut saws, stone-breaking hammers and pile drivers. Because road-building is one of the engineers’ most important tasks, road scrapers and other highway construction machines are included. Instead of doing their work in comparative safety - behind the lines - the engineers operate in war in the forward part of the combat zone - mainly to assist the other fighting arms. In emergencies, when the need for reserves is more pressing than the need for engineering work, units of combat engineers go into battle against the enemy. Often the combat engineers have the hazardous task of clearing the way for bridge-building units to throw a pontoon span across a stream or ravine - and that means fighting if the enemy is inclined to contest the advance. The combat troops launch their small assault boats and move out on the water, eyeing the opposite shore and keeping weapons in readiness. Another important phase of the engineers’ work is surveying and mapping. This includes not only preparing maps, but producing them in quantities by printing or other means, and distributing them to the other arms and services. There are also special units, such as camouflage, pontoon, railway, water supply, dump truck and shop companies. All these many tasks have two simple purposes in time of war. One is to make the movement and supply of Uncle Sam’s Army easier. The other is to hinder the movement of the enemy. In peacetime the engineers direct rivers and harbors improvement, flood control and other public works. In the early days of this nation’s expansion, Army engineers located, constructed and even operated railroads, such as the Baltimore and Ohio, the Erie, the Boston and Albany, and were in a large measure responsible for completing the first transcontinental lines. In the course of his life career in the Army, an officer of the Corps of Engineers may spend a full half of his time on civil works duties. Such work is invaluable in training the engineers for the huge tasks of construction required of them in war. They built and maintained, in the World War, railroads, roads, bridges, wharves, docks, warehouses, barracks and hospitals, and water supply, electric power and other utilities systems needed in France for an army of 2,000,000 men.