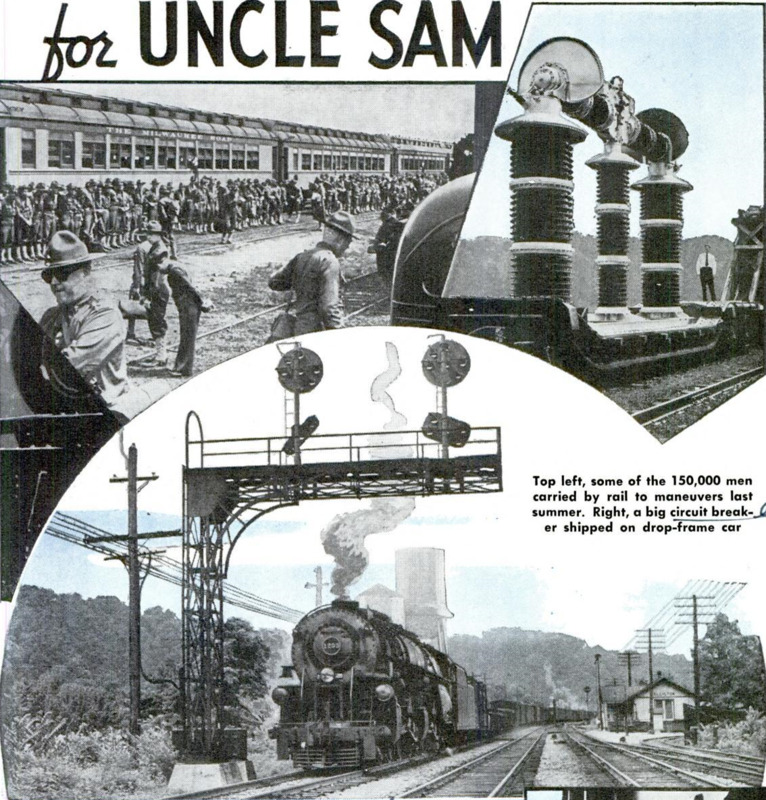

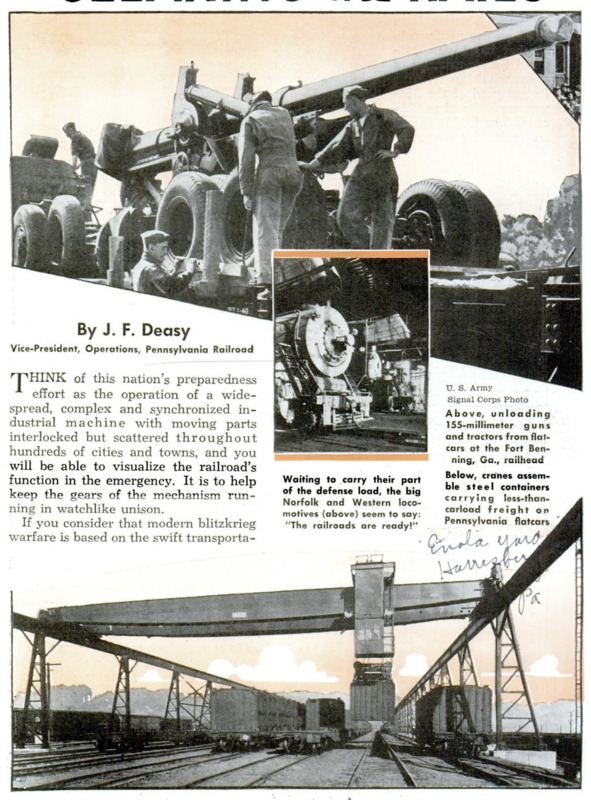

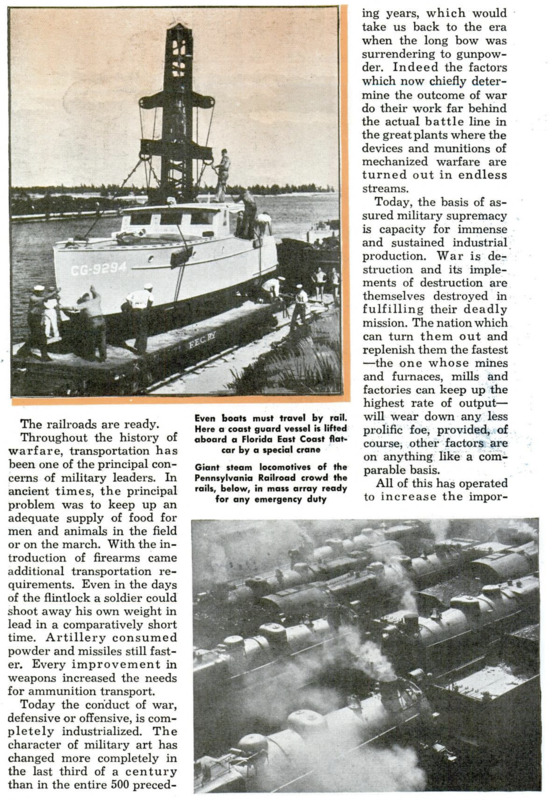

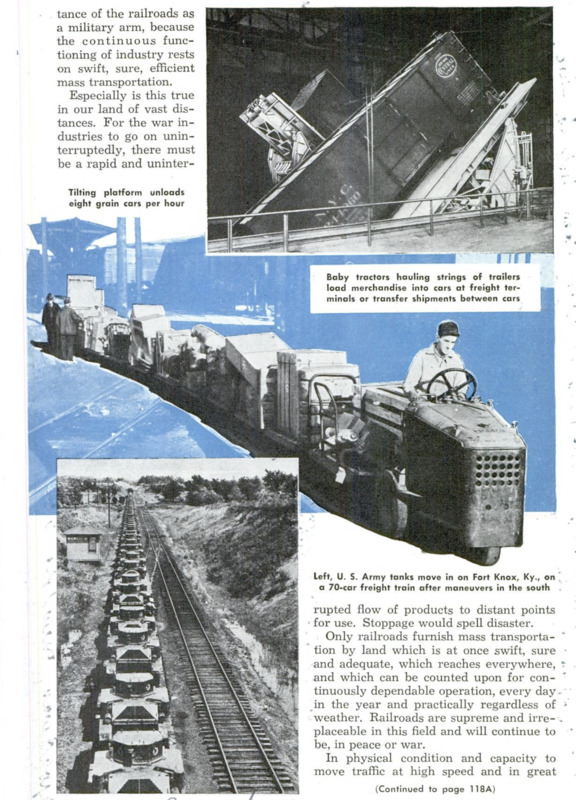

THINK of this nation’s preparedness effort as the operation of a widespread, complex and synchronized industrial machine with moving parts interlocked but scattered throughout hundreds of cities and towns, and you will be able to visualize the railroad’s function in the emergency. It is to help keep the gears of the mechanism running in watchlike unison. If you consider that modern blitzkrieg warfare is based on the swift transportation of another intricate but destructive machine - the mechanized army - then you can see that in America the railroads are virtually the mainsprings of defense. We Americans have two seacoasts, 3,000 miles apart and two international boundaries 1,200 miles apart, any one or all of which might have to be defended should war come to us. If the wheels of defense are going to turn efficiently in such a far-flung land, the railroads must supply the impetus which will make the whole thing tick. You may begin to wonder if the railroads are ready to carry this important load for defense. In behalf of the railroad men of the nation, from crossing watchman to chairman of the board, I give you the answer. The railroads are ready. Throughout the history of warfare, transportation has been one of the principal concerns of military leaders. In ancient times, the principal problem was to keep up an adequate supply of food for men and animals in the field or on the march. With the introduction of firearms came additional transportation requirements. Even in the days of the flintlock a soldier could shoot away his own weight in lead in a comparatively short time. Artillery consumed powder and missiles still faster. Every improvement in weapons increased the needs for ammunition transport. Today the conduct of war, defensive or offensive, is completely industrialized. The character of military art has changed more completely in the last third of a century than in the entire 500 preceding years, which would take us back to the era when the long bow was surrendering to gunpowder. Indeed the factors which now chiefly determine the outcome of war do their work far behind the actual battle line in the great plants where the devices and munitions of mechanized warfare are turned out in endless streams. Today, the basis of assured military supremacy is capacity for immense and sustained industrial production. War is destruction and its implements of destruction are themselves destroyed in fulfilling their deadly mission. The nation which can turn them out and replenish them the fastest - the one whose mines and furnaces, mills and factories can keep up the highest rate of output - will wear down any less prolific foe, provided, of course, other factors are on anything like a comparable basis. All of this has operated to increase the importance of the railroads as a military arm, because the continuous functioning of industry rests on swift, sure, efficient mass transportation. Especially is this true in our land of vast distances. For the war industries to go on uninterruptedly, there must be a rapid and uninter rupted flow of products to distant points for use. Stoppage would spell disaster. Only railroads furnish mass transportation by land which is at once swift, sure and adequate, which reaches everywhere, and which can be counted upon for continuously dependable operation, every day in the year and practically regardless of weather, Railroads are supreme and irreplaceable in this field and will continue to be, in peace or war. In physical condition and capacity to move traffic at high speed and in great volume, the railroads are at their peak. Within the last 20 years, our railroads have been practically rebuilt and in their essential features are actually new, though the art of rail transportation itself has a century of experience behind it. When transportation service is required in astronomical quantities, whether in war or in peace, the railroads leave other agencies almost out of the picture. Let us assume the army of the United States is increased to a million and a half men actively under arms. That means the railroads must carry a million and a half soldiers where and when the authorities direct. It will be a big job and no one realizes it better than we railroad men do. What is not generally realized, I believe, is the fact that in everyday work our railroads are thoroughly experienced in handling immense mass movements of civilian passengers, larger in volume than any individual movement likely to be required even in actual war. To illustrate, at recent Presidential inaugurations we have operated from 90 to 100 trains to and from Washington, and handled 50,000 passengers in and out of the capital in one day. The annual Army-Navy football game at Philadelphia averages 80 special trains and more than 45000 inbound and outbound passengers on our rails alone. Every inviting weekend of the summer we carry to and from seashore resorts of Southern New Jersey 100,000 or more passengers - 50,000 to the beaches and 50,000 back - requiring nearly 300 trains, and mostly concentrated from Saturday noon to Sunday evening. Over the last Labor Day weekend, three-quarters of a million traveled on 2,000 trains shuttling between Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York, the summer resorts along the North Atlantic and points to the west and south. At Pennsylvania station in New York City, over 69,600,000 passengers arrived and departed during 1939, an average of more than 190,000 a day. These great civilian mass movements are all army-size, some of them much more than army-size. They are concentrated for the most part into shorter periods than army movements ordinarily require and, except in the case of Pennsylvania station, they are movements over only one railroad out of many in the country. Last summer the nation witnessed an impressive demonstration of fast troop movements by rail. The Regular Army and National Guard training maneuvers in northern New York, Wisconsin, Louisiana, Minnesota and Washington involved assembling 150,000 men from every state, traveling over practically every Class 1 railroad. In one period of three days 105,000 men were moved by rail, which considerably exceeded in volume anything carried out in the most active period of the first World War, when this nation mobilized 4,000,000 soldiers and sent 2,000,000 overseas. I realize, of course, that these training maneuvers were not a test of the capacity of the railroads to handle a modern mechanized army on a war footing, while at the same time maintaining the transportation service necessary for munition factories working at wartime outputs. I realize also that conditions have changed since the last World War; but so have our railroads. The average power of freight locomotives in that time has increases 44 per cent, the capacity of freight cars 20 per cent, and the speed of freight trains by nearly two-thirds. The output of transportation service - the ton-miles per hour of train operation - has considerably more than doubled. Freight cars of greatly improved types have rendered loading and unloading faster and more efficient. In the first nine months of 1940, American railroads put 52,658 new freight cars in service. These factors bespeak tremendous gains in capacity to move freight promptly, and progress in passenger transportation has been fully as great. It may be of interest to know that passenger cars of American railroads could seat 1,738,645 passengers at one time; that the 1,700,000 freight cars in service, coupled with the necessary locomotives, would make a train 17,000 miles long and capable of carrying 84,000,000 tons. Every day 33,200 freight and passenger trains operate in the United States, so that somewhere in the country a train is starting on its run every two and two-thirds seconds. Figures such as these may help to visualize the tremendous capacity which the railroads of America have available for the service of the nation in war or peace.