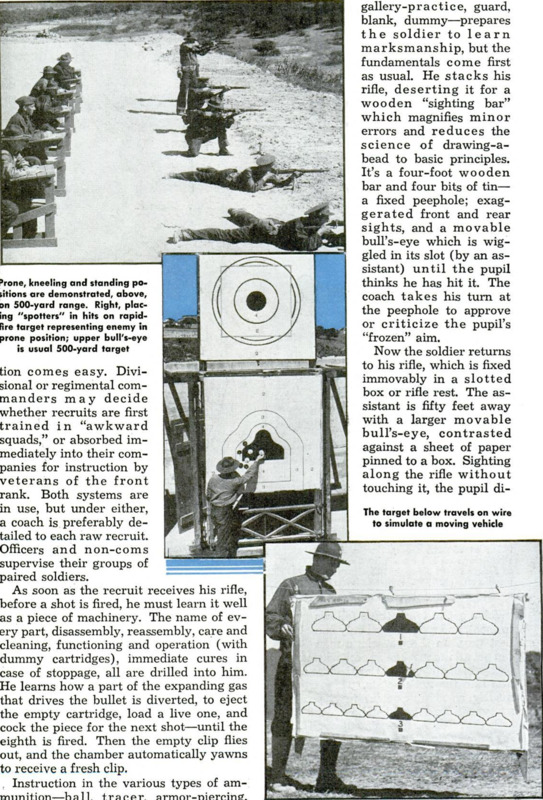

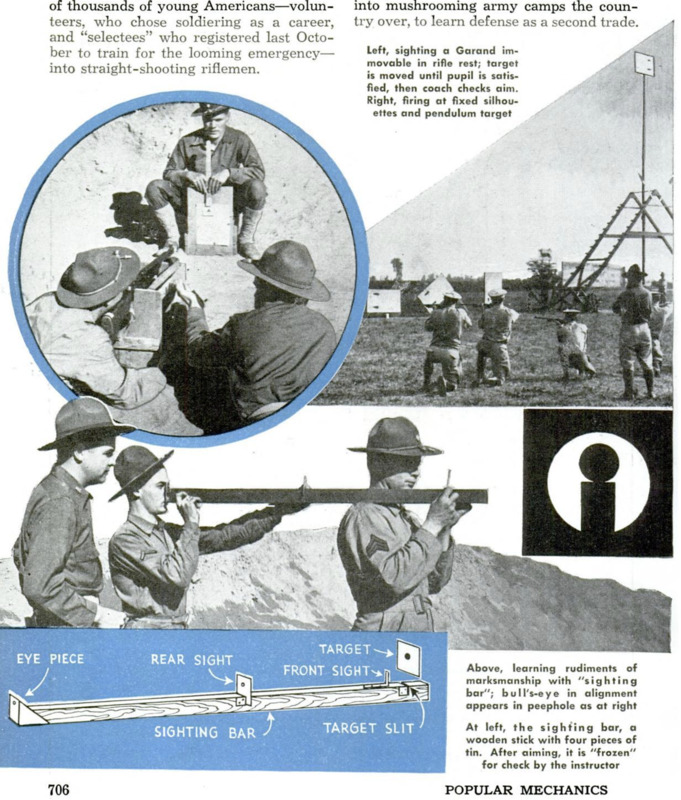

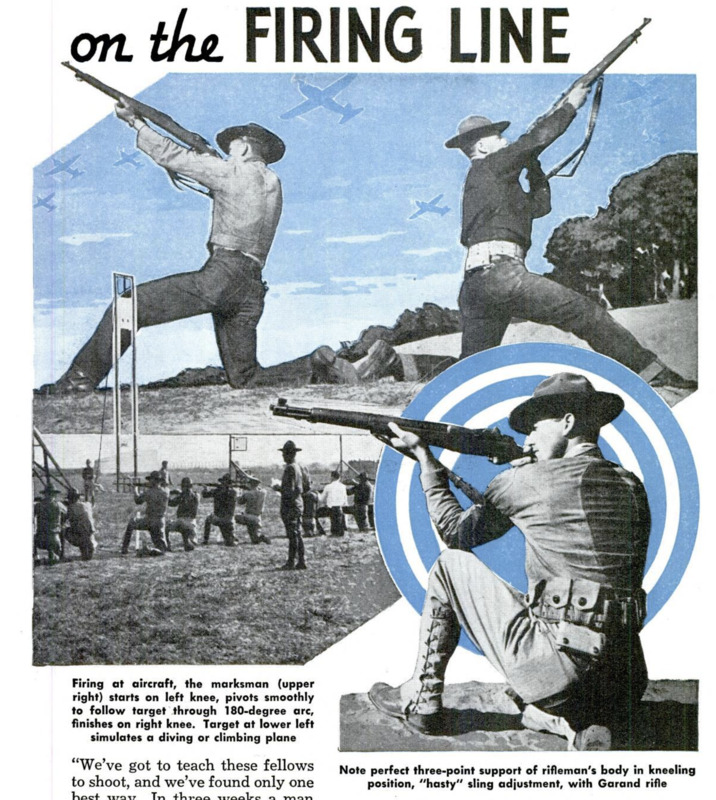

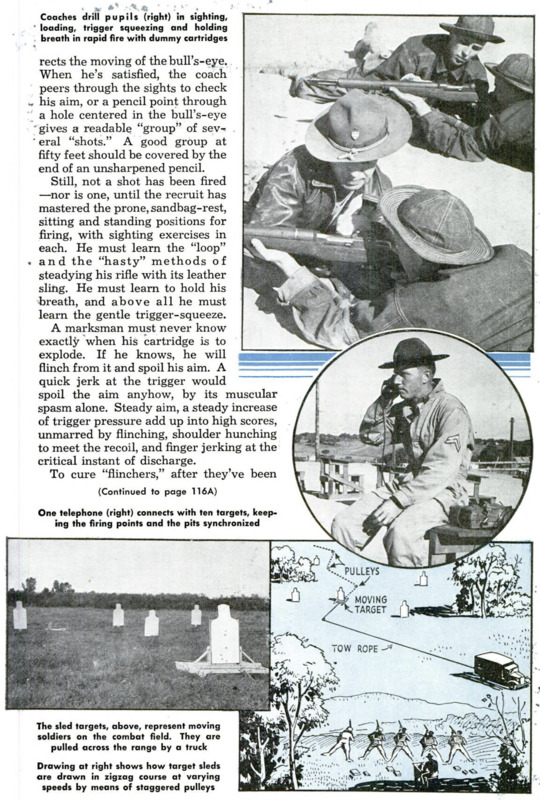

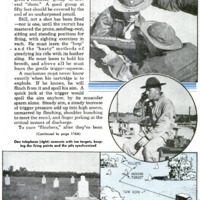

FIRST they send all the student buglers deep into the woods around camp, lest their snortings disturb a serious business, Then the Army settles down to its problem of turning hundreds of thousands of young Americans - volunteers, who chose soldiering as a career, and “selectees” who registered last October to train for the looming emergency - into straight-shooting riflemen. “A soldier’s a soldier, whether for one year, three years, or a lifetime,” said a major thoughtfully, referring to the salesmen, bank clerks, barbers - the young men of every trade and no trade who are pouring into mushrooming army camps the country over, to learn defense as a second trade. “We've got to teach these fellows to shoot, and we've found only one best way. In three weeks a mancan get all the mechanics of marksmanship, and gain confidence. After that we can get him into the finer points. They won't all qualify as sharpshooters in a year, but many will. And they’ll all be real riflemen.” So the selectees are going through Course A of the Basic Field Manual for U. S. Rifle Caliber .30 M1, generally known as the Garand. The Army believes with reason that it has one of the best marksmanship courses of all the world’s armies, and oneof the best rifles. Training begins with intensive physical drill - calisthenics, ball games and boxing for wind and limb, so that a man can hold firing position steady-on, without fatigue. It ends with mastery of a self-loading rifle, gas-operated and air-cooled which will fire eight straight shots in two seconds. Save for preliminary lectures the Army likes to train its marksmen man-to-man, rather than in large classes where inattention comes easy. Divisional or regimental commanders may decide whether recruits are first trained in “awkward squads,” or absorbed immediately into their companies for instruction by veterans of the front rank. Both systems are in use, but under either, a coach is preferably detailed to each raw recruit. Officers and non-coms supervise their groups of paired soldiers. As soon as the recruit receives his rifle, before a shot is fired, he must learn it well as a piece of machinery. The name of every part, disassembly, reassembly, care and cleaning, functioning and operation (with dummy cartridges), immediate cures in case of stoppage, all are drilled into him. He learns how a part of the expanding gas that drives the bullet is diverted, to eject the empty cartridge, load a live one, and cock the piece for the next shot - until the eighth is fired. Then the empty clip flies out, and the chamber automatically yawns to receive a fresh clip. Instruction in the various types of ammunition - ball, tracer, armor-piercing, gallery-practice, guard, blank, dummy – prepares the soldier to learn marksmanship, but the fundamentals come first as usual. He stacks his rifle, deserting it for a wooden “sighting bar” which magnifies minor errors and reduces the science of drawing-a-bead to basic principles. It's a four-foot wooden bar and four bits of tin - a fixed peephole; exaggerated front and rear sights, and a movable bull's-eye which is wiggled in its slot (by an assistant) until the pupil thinks he has hit it. The coach takes his turn at the peephole to approve or criticize the pupil's “frozen” aim. Now the soldier returns to his rifle, which is fixed immovably in a slotted box or rifle rest. The assistant is fifty feet away with a larger movable bull's-eye, contrasted against a sheet of paper pinned to a box. Sighting along the rifle without touching it, the pupil directs the moving of the bull’s-eye. When he's satisfied, the coach peers through the sights to check his aim, or a pencil point through a hole centered in the bull's-eye gives a readable “group” of several “shots” A good group at fifty feet should be covered by the end of an unsharpened pencil. Still, not a shot has been fired - nor is one, until the recruit has mastered the prone, sandbag-rest, sitting and standing positions for firing, with sighting exercises in each. He must learn the “loop” and the “hasty” methods of steadying his rifle with its leather sling. He must learn to hold his breath, and above all he must learn the gentle trigger-squeeze. A marksman must never know exactly when his cartridge is to explode. If he knows, he will flinch from it and spoil his aim. A quick jerk at the trigger would spoil the aim anyhow, by its muscular spasm alone. Steady aim, a steady increase. of trigger pressure add up into high scores, unmarred by flinching, shoulder hunching to meet the recoil, and finger jerking at the critical instant of discharge. To cure “flinchers,” after they've beenexposed by bad scores in firing, the Army may slip them dummy cartridges – just often enough so they won’t know whether the piece will fire or not - and can’t flinch from it. Or the coach, prone beside his pupil, may squeeze the trigger, getting better scores from that pupil’s aim than the flincher gets by himself - until he’s cured. But that comes later, after drill in rapid fire technique, windage, elevation, light and mirage has readied the selectee to smell powder. Al this preparatory training has gone on for about two weeks on the company street, the parade ground or anywhere, but now a target range is required. Here's a bottleneck, for the safety precautions only begin with a vast empty danger area in line of fire. Ranges are busy seven days a week, dawn to dusk, and range capacity is being doubled and redoubled so fast that today’s statistics would be ancient history next week. During instruction practice with known-distance targets, the coach remains at the pupil’s elbow. It begins at 1000~inch range, often with .22 caliber equipment, progressing into ranges of 200, 300 and 500 yards with the M1 rifle. It begins with unlimited time to fire four shots, and gets tougher until a man must drop from standing to prone and pump sixteén shots into the 300-yard target within sixty-five seconds. It includes all four body positions; it burns at least 140 rounds of ammunition, with careful marking and scoring of each shot and constant correction of errors - and it prepares the selectee for his record practice. Now he’s on his own, with no coach, to prove himself a rifleman. In Course A he fires twenty shots slowly, forty-eight rapidly, using all four positions, and ranges of 200, 300 and 500 yards. He stands or falls on this record. If he falls, he returns to his coach. If he stands, he goes on into field training under simulated combat conditions - unknown ranges, moving targets, antiaircraft firing, in all their finer points. He learns to find a small target in a big landscape, by verbal description or tracer bullet. He learns to “lead” a moving target, firing at the forward half of a man walking at close range, and five lengths or more in advance of a hostile airplane, depending upon the angle. Vehicles are simulated by boxlike targets mounted upon sturdy sleds, towed across the combat range by hidden trucks. A series of staggered pulleys and a trip knot in the tow rope give the target-carrying sled a zigzag course at momentarily varying angles. Antiaircraft marksmanship, essential in modern warfare, requires a new firing position. Erect (not squatting) on one knee, with the other foot well advanced, the rifleman can swing his body smoothly to “hold” on the target for an arc of 180 degrees as it flashes past, ending on the other knee. Targets at first are silhouettes on a miniature range of 500 inches. They travel on overhead wires at fifteen to twenty feet per second, simulating overhead, non-overhead, diving and climbing planes. Firing is by groups, and obviously the range must have a huge danger area. Even more elaborate safety measures are required for the final phase - group firing into a sleeve target towed by an airplane. So runs the course of training America back into the Daniel Boone sharpshooting tradition. “Any man physically and mentally capable of being a soldier can be taught to shoot well,” says the Army. “This for many years has been the basic principle of rifle marksmanship in the Army, and experience has proved it correct. It is not unusual for an organization to qualify every single man, in the course of a training season, with a high percentage of experts and sharpshooters among them.” Many a mechanic, technician or bugler may put in his year of training without ever drawing a bead with a Garand, it's true. But the backbone of this man’s army is the able, self-reliant rifleman still, and the Army knows how to face this crisis with a sturdy backbone in the old American way.