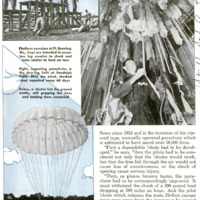

AFTER the daily battle of the skies comes the British war communique, grim however you look at it. But the figures most important to a certain group of aviation scientists are those in the sentence reporting that, of a number of Royal Air Force planes shot down, “the pilots of five are safe.” From day to day the tally varies, the balance sheet of the lost and the lucky. What encourages the parachute technicians is the imposing record given in a recent R. A. F. summary. It showed that nearly 85 percent of the British fiyers shot down had been saved by their 'chutes. Figures like these, covering the most adverse conditions of war, indicate the parachute makers have brought their science to a high level. Just a few years ago the parachute was regarded with grave suspicion. James Floyd Smith, vice president of the Pioneer Parachute Company at Manchester, Conn., recalls that it was considered suicide-to-jump from a plane, for it was believed that the fiyer would lose consciousness before the 'chute could open. Smith hasflown since 1912 and is the inventor of the ripcord type, manually operated parachute which is estimated to have saved over 10,000 lives. “First a dependable ’chute had to be developed,” he says, “then the pilots had to be convinced not only that the ‘chutes would work, but that the free fall through the air would not cause loss of consciousness, or the shock of opening cause serious injury. “Then, as planes became faster, the parachute had to be correspondingly improved. It must withstand the shock of a 200 pound load dropping at 300 miles an hour. And the pilot ‘chute which releases the main 24-foot canopy must open away from the jumper so he cannot be fouled. With faster and faster planes predicted, constant improvementsare being made.” An important step in this direction was the recent installation of a testing tower at Manchester, Conn,, the first in America, to conduct parachute research under flying conditions. New ways of packing 'chutes and certain structural improvements already have been developed as a result of these tests. From this 50-foot tower a dummy equipped with a parachute pack is whirled at 70 to 300 miles an hour. When the dummy attains the desired speed the parachute is automatically released, and ’chute and dummy float to earth. Meanwhile a motion picture camera, moving with the boom, takes a slowmotion record of the parachute opening. This has brought to light many important facts. In many cases, it showed the pilot ‘chute, supposed to open first, was the last to operate. This hazard had to be eliminated, as it could foul the main canopy and lines. An improved pilot ‘chute was developed and packing of the main canopy changed so that it is virtually impossible for the skirt of the canopy to be tilted up in opening, an occurrence that used to account for many parachute failures. Spectators have seen exhibition jumpers step out of level-flying planes and descend gracefullybeneath 28-foot exhibition canopies. “Leaping from a spinning, burning or diving plane hit by a shell or bullets from an enemy plane is quite another thing,” says Mr. Smith. “To get clear of a plane in a situation like this, a self-contained parachute pack is essential. It is used by all the warring nations with the exception of German parachute troops, who use a static-line ’chute. This type is fastened to the plane by a cord which breaks under the weight ofthe jumper, pulling out the canopy. It permits a jump from very low altitude.” Static-line "chutes were used by British pilots late in the World War and they were in use on that day in 1914 when Smith crashed a plane he was testing for Glenn Martin. He was flying at 1,500 feet when the right wing folded back, and he went into a spin. By adroit use of elevators, one good aileron and power he went into a power dive and pulled out a few feet above ground for a crash landing. Then and there he determined to develop a ’chute which would open when he jumped clear of a disabled plane. People told him he was crazy, that the scientists agreed a man lost consciousness as he fell. Smith laughed, for as a circus aerialist he had fallen without losing consciousness. Finding muslin and other experimental materials too heavy he turned to silk and devised a means of packing the ’chute so a flyer could sit on it or lean against it comfortably. Nothing came of his invention until the terrific mortality among pilots during the World War set army officers to thinking. When General William Mitchell, who commanded the American air force in France, inquired who knew about parachutes, Smith was given his opportunity to develop his invention at McCook Field. For months Smith and an assistant, Guy Ball, sewed parachutes and dropped them from a plane, with lead dummies attached. Smith was about ready to make the first jump when a youth of 22, Leslic L. Irvin, arrived at the field April 28, 1919, with orders to make the first “live” jump with Smith’s new ’chute. Smith piloted the plane. The crowd which gathered was sure Irvin was committing suicide, but he was as confident as Smith, though in his excitement Irvin didn’t remember to watch himself in landing and broke his ankle. Irvin, too, lived to become a leading parachute manufacturer. Soon, the parachute proved its worth under dramatic circumstances. One October day in 1922, Lieut Harold Harris was flying 2,500 feet above McCook Field when a wing buckled. He jumped, counted five and pulled what he thought was the ripcord. Nothing happened. Again he tugged frantically, then discovered he had been pulling on a leg strap. Harris fell more than 2,200 feet before he located the ripcord. At an altitude of less than 300 feet, his 'chute suddenly snapped open and landed him without injury. He had made the first chronicled emergency jump with a ripcord, manually operated ’chute. He had made the first delayed-opening jump of 2,200 feet and had become the first member of the Caterpillar Club. From then on, many false theories were disproven. Capt. A. W. Stevens showed that a parachute would function from great heights by bailing out at 26,500 feet, and James Floyd Smith made a pull-off jump at 100 feet. James Russell dived head foremost from 200 feet, his 'chute landing him without difficulty. Spud Manning dove from more than two and a half miles up and didn’t pull his ripcord until near the ground. The parachute was achieving a reputation for reliability. “In fact,” points out Ronald Colwell, a veteran of 521 jumps, now in the Army Air Corps, “accidents are caused by carelessness, and the good jumpers die in bed” In an 1l-year study of parachute jumping Colwell has found no physical reactions other than temporary loss of hearing. Nor is there a feeling of dizziness, but rather of suspension, without the slightest sensation of falling until near the earth. “The greatest danger in "chute jumping,” Colwell says, “is steerage of the parachute by slipping - closing the canopy by pulling on the shroud lines. One might pull them too far, and if that happens at a very low altitude, the chute will collapse and plummet to earth.” He warns that unless one is familiar with the operation and function of parachutes, he should not under any circumstances attempt a delayed opening at any time. This should be left to professionals, while others forced to take to aerial life preservers should pull their ripcords after counting up to five. Capt. Harry G. Armstrong of the Army Air Corps, fell nearly a thousand feet before pulling his ripcord and noted that his mind was “rapid, precise, penetrating and clear.” Strangely enough, the irritating effects of the wind, which smarted his eyes when he sat in the cockpit without goggles, disappeared when he jumped and his vision was perfectly clear. Like Colwell, he became physically conscious of the fact that he was falling only when he could clearly see the ground, at about 1,900 feet. Before he jumped he could distinguish the sound of the motors of several planes but during his fall he was momentarily deaf. He felt no rush of air until near the ground, when there was a gently increasing sensation of air pressure, as if he were sinking into a feather bed.