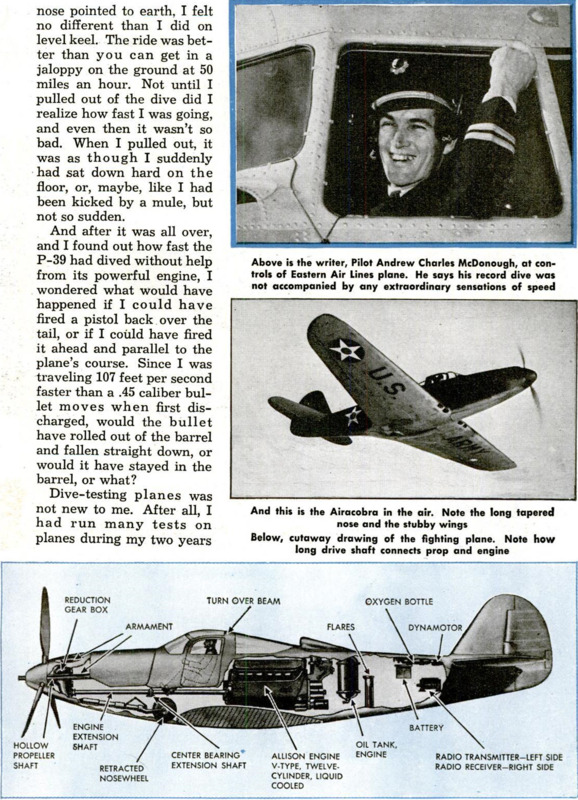

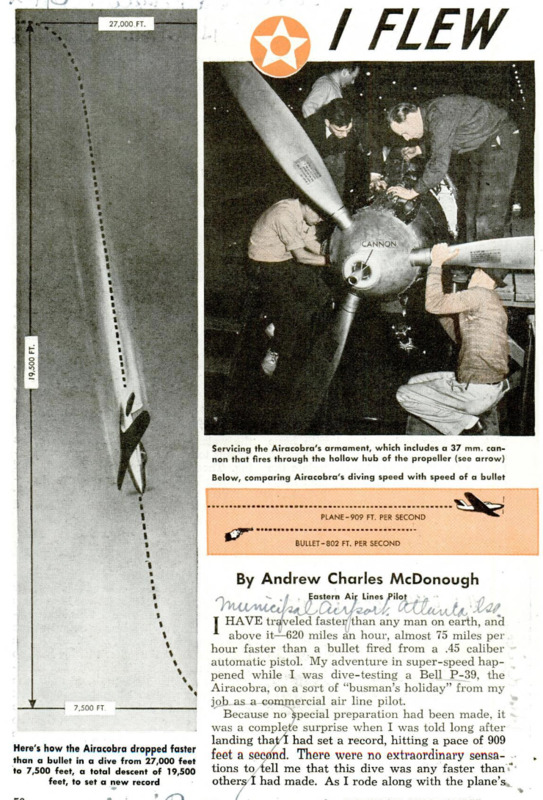

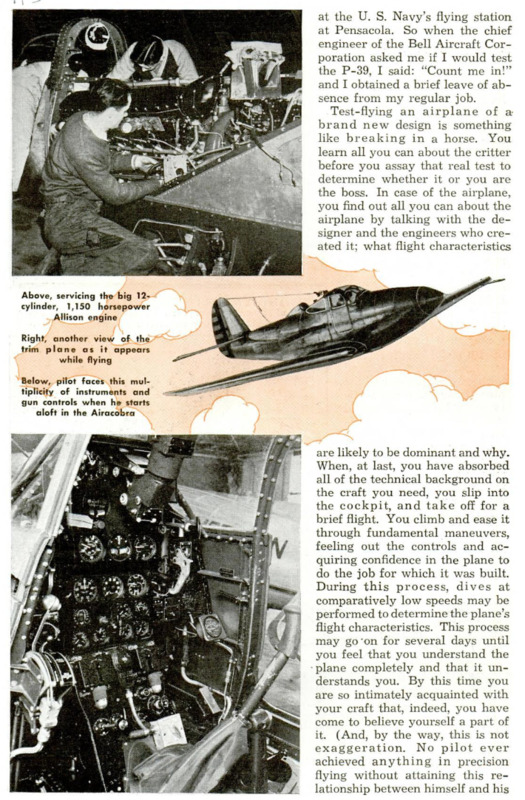

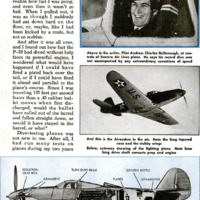

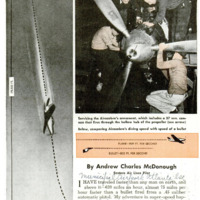

I HAVE traveled faster than any man on earth, and above it - 620 miles an hour, almost 75 miles per hour faster than a bullet fired from a .45 caliber automatic pistol. My adventure in super-speed happened while I was dive-testing a Bell P-39, the Airacobra, on a sort of “busman’s holiday” from my job as a commercial air line pilot. Because n:}pecinl preparation had been made, it was a complete surprise when I was told long after landing that I had set a record, hitting a pace of 909 feet a ind. There were no extraordinary sensations to tell me that this dive was any faster than others I had made. As I rode along with the plane’s, nose pointed to earth, I felt no different than I did on level keel. The ride was better than you can get in a jaloppy on the ground at 50 miles an hour. Not until I pulled out of the dive did I realize how fast I was going, and even then it wasn’t so bad. When I pulled out, it was as though I suddenly had sat down hard on the floor, or, maybe, like I had been kicked by a mule, but not so sudden. And after it was all over, and I found out how fast the P-39 had dived without help from its powerful engine, I wondered what would have happened if I could have fired a pistol back over the tail, or if I could have fired it ahead and parallel to the plane’s course. Since I was traveling 107 feet per second faster than a .45 caliber bullet moves when first discharged, would the bullet have rolled out of the barrel and fallen straight down, or would it have stayed in the barrel, or what? Dive-testing planes was not new to me. After all, I had run many tests on planes during my two years at the U. S. Navy's flying station at Pensacola. So when the chief engineer of the Bell Aircraft Corporation asked me if I would test the P-39, I said: “Count me in!” and I obtained a brief leave of absence from my regular job. Test-flying an airplane of a brand new design is something like breaking in a horse. You learn all you can about the critter before you assay that real test to determine whether it or you are the boss. In case of the airplane, you find out all you can about the airplane by talking with the designer and the engineers who created it; what flight characteristics are likely to be dominant and why. When, at last, you have absorbed all of the technical background on the craft you need, you slip into the cockpit, and take off for a brief flight. You climb and ease it through fundamental maneuvers, feeling out the controls and acquiring confidence in the plane to do the job for which it was built. During this process, dives at comparatively low speeds may be performed to determine the plane’s flight characteristics. This process may go-on for several days until you feel that you understand the plane completely and that it understands you. By this time you are so intimately acquainted with your craft that, indeed, you have come to believe yourself a part of it. (And, by the way, this is not exaggeration. No pilot ever achieved anything in precision flying without attaining this relationship between himself and his craft.) That is just what I did with the P-39 the day of the final test flight. As I walked onto the field the Airacobra was being warmed up. A trim, stubby winged little plane with a long tapered nose mounting a three-blade Curtiss electric propeller, it is powered by a 12-cylinder, 1,150-horsepower Allison Prestone cooled engine placed at the rear of the pilot’s compartment. The propeller operates off a long drive shaft which extends from the engine, below the pilot, to the propeller gear box. In the nose are the deadly stingers of the Airacobra, a 37 mm. explosive shell firing cannon and two .50 caliber machine guns; in the wings are mounted four .30 caliber machine guns. This is the interceptor pursuit plane which packs a withering fire in addition to its phenomenal speed and maneuverability. The Airacobra carried a full military load in all respects during the tests. This was not a test on the engine but rather on the plane to determine its ruggedness at maximum dive speed. I climbed, climbed, climbed. The ice cream clouds spread a vast blanket separating me from the earth, reminding me that I could thank my cabin’s efficient heating system for the comfort I was enjoying. At 14,000 feet I put on the oxygen mask, for I was going even higher. I continued circling and climbing until I reached 27,000 feet; then reached back over my head and turned a switch in a box there. The box contained a fixed-focus motion picture camera trained on the faces of the altimeter, airspeed indicator, clock, thermometer and many other instruments. I called the ground crew: - “Will now dive from West to East” - and adjusted the controls changing over from level flight to dive. This was not to be a power dive, with the big engine going full blast. Instead it was a “free” dive, with the propeller turning just fast enough to keep the engine warm, Now, for the real test! Stick forward, and I fell easily into the dive. My sensa- tion was, at first, one of falling into a pit. Then I began feeling that I was falling right with the ship, as though suspended in space. The wind screamed around the gun barrels protruding from the nose cowling. Higher, higher, higher the scream rose, finally attaining a steady pitch, Soon my ears grew accustomed to the sound; I lost all sense of gravity; I was slipping through the air as slick as a hot knife through butter. A glance at the instruments showed that my almost vertical descent had wound up the air speed needle on the instrument panels. It was past 500. Knowing that 40 miles per hour would be added on the pullout, I started leveling off, pulling out at 7,500 feet. Wham! That felt like a kick from a mule, but it was only the arresting of my speed. The Airacobra took the pullout without a tremor, slitting through the sky and showing an indicated air speed of 523 miles per hour on the instrument panels. My altitude at level was now 5,000 feet. “Dive completed,” I radioed the ground station. Returning to base.” I landed the little silver bullet and stepped from the cockpit. An examining physician gave me a minute going over, just in case, but pronounced me in tip-top shape except for an exhausted feeling. No two ways about it, testing is a strain on any pilot. After such dives some pilots develop a condition comparable to the “bends” that affect divers working under water, The Airacobra “doctors” made their examination and turned in their report. No evidence of skin wrinkles or other symptoms of strain. Technicians removed the movie film and ran their calculations on the airspeed readings, temperature and pressure indications. Then came the amazing news that my plane had flown at a faster speed than any ever recorded: 620 miles per hour, the engineers calculated, allowing for all customary corrections that are used in figuring speed in this type of test. Most fast aircraft must be “flown” all the time; but in such a ship as the P-39 the pilot is fortunate to have a craft which responds so easily to his wishes and has so many safety devices built into its structure. For instance, if the pilot should ever have to bail out of an Airacobra he would find the problem very simple. On both sides of him are doors similar to those in an automobile. If he has any doubts about his ability to open either of the cabin doors because of the tremendous wind action all he needs do is pull a latch which knocks the door off its hinges and the door automatically falls away from the plane. This is most important because the slipstream of air around the airplane at high speeds is almost like a solid brick wall. At 475 m.p.h., for example, the slipstream is the same consistency as water, and at 500 m.p.h. it is as though you were being pulled under water at 120 miles an hour. This problem has given England’s R. A. F. some concern. It is impossible to bail out of some fighter airplanes unless they are turned over on their back. In this position once his cockpit cover has been pushed back the pilot merely releases his seat belt and tumbles earthward from his cockpit. Because it is not always possible to turn the plane upside down, particularly during times of emergency, when bailing out is required, the door features of the Airacobra are especially appreciated. All pursuit ships and dive bombers must be tested to determine terminal velocity, namely; the speed at which the ship - at its particular weight - will fall, When your ship is building up to terminal velocity you are actually falling free with the craft. No object which is loose in the cockpit has any weight, in the accepted sense, because it is falling at about the same speed as the plane. For example, in a dive I have seen a fire extinguisher break loose from its hanger and “float” around the cockpit until I lifted it out of the air and tucked it under my leg. The only thing certain about plane speed records is their impermanence. For example, only a few years ago students of aerodynamics believed a speed of 400 miles per hour would set up a vibration so destructive it would whip a plane to pieces. But a plane was built and a test pilot flew it to demonstrate that theories do not always stand up. Today many experts are saying that when a plane reaches 720 miles per hour, the speed of sound, the center of lift will shift forward to the leading edge of the wing, collapsing that supporting structure. This theory will be put to actual test sooner than we think, because new, faster planes are now on the drafting boards of our airplane factories.

Popular Mechanics, v. 76, n. 1, 1941

Popular Mechanics, v. 76, n. 1, 1941